One of my earliest memories is of visiting my Aunt Karen in the hospital shortly before we lost her to breast cancer. I was too little to remember much, but I remember thinking that in her mid-30s my aunt was too young to die—dying was for old people.

Earlier this month, another of my mom’s sisters was diagnosed. Not only was this yet another blow to the family, it marked a pattern. After worried warnings spread from mothers to daughters, the females in my family are now on high alert. My mom has had a few irregular mammograms and is no stranger to the anxiety, but my cousins and I—all in our 20s—haven’t even had our first mammograms. Yet.

Now, we await the results of tests to see if my aunt has a mutation in one or both of her BRCA genes, which ordinarily serve as a line of defense against cancer. If she tests positive for the mutation, her immediate family members will be tested, my mom among them. If she tests positive, then I will get tested. Because insurance companies pay $3,000 for each test, it is difficult to get approved for coverage without at least one immediate family member being diagnosed with breast cancer.

So, we wait.

If someone tests positive for a BRCA mutation, there is a 70 to 80 percent chance of contracting breast cancer and 30 to 40 percent chance of contracting ovarian cancer through the end of life, said Baystate Medical Center oncologist and breast cancer specialist Dr. Grace Makari-Judson. On the flip side, if tests are negative, that in no way signals someone is free and clear. Most breast cancers arrive without a genetic warning sign, experts say.

In addition to looking for ways in which genetic predisposition can signal an increased risk of cancer in a person, researchers have been exploring how deeper study of particular genes and their development (or “expression”) can improve treatment for individual patients.

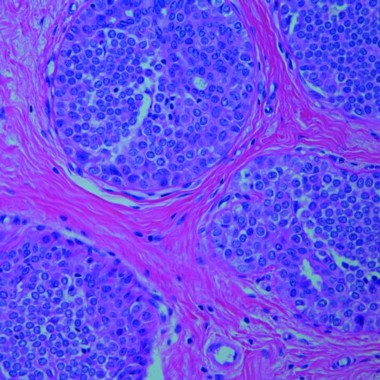

According to Makari-Judson, the disease that claimed my Aunt Karen two decades ago may not be the same disease that my Aunt Debbie was recently diagnosed with. In fact, no two tumors are identical. Health care researchers and providers are just beginning to grasp how complex and varied breast cancer truly is. There are at least five different subtypes and, in terms of prognosis and treatment, each may as well be a different disease entirely.

“Breast cancer is a lot of different diseases,” Makari-Judson says. “Now, when we treat breast cancer, we look at the tumor to get an idea of some of the molecular aspects so we can target our treatment to that specific tumor.”

With funding from the National Institutes of Health and a number of other organizations, including Springfield’s Rays of Hope Foundation, Makari-Judson and her colleagues at Baystate are working closely with lab-based researchers to make advancements and improve treatment in real-time. UMass veterinary and animal sciences professor Joseph Jerry, who has long studied mammary tumors in animals, works alongside Makari-Judson to draw parallels between simplified animal models and their more complicated human counterparts. Together, Makari-Judson and Jerry direct the Rays of Hope Center for Breast Cancer Research at Baystate.

Jerry explains that, while we know much more about the genetic landscape than we did a decade ago, there’s more work to be done. Scientists have identified the full range of genes that make up the human genome, but still have work to do to learn how all these genes express themselves—and sometimes go astray to form cancers.

“A decade ago, we were looking for a genome map—that’s done,” Jerry says. “Now, it’s different. Now we have the genome map. We know the roads. We know where we want to get to in some ways, but we find it’s a little more complicated because there are traffic jams along the way we didn’t anticipate.”

Using the breast cancer registry at the center, which has grown rapidly through the active participation of Valley women, Makari-Judson and Jerry are working to paint a genomic portrait of what the disease looks like in each patient. They look at 40,000 different genes in the individual, looking not only at inherited genes that confer breast cancer risk, but also at how various life exposures change gene expression over time and how these expressions change during cancer development. Jerry likens this research to taking a satellite view of traffic patterns to see where there are disruptions inhibiting flow of information and gene expression. He explains that by tracking where these disruptions occur in each individual, he and the team are able find patterns in the cancer’s behavior and response to treatment.

“People’s molecular profiles, beyond genes related to susceptibility to cancer, may help predict how somebody would tolerate a particular medicine,” says Makari-Judson. “And so this is what the area of personalized medicine is really going to be all about—not just looking at the right treatment based on the tumor but the right treatment based on the individual host.”

Now we are at this awkward point in breast cancer research where we know a lot about the disease, but perhaps not necessarily enough to act on. In my case, for instance—I keep asking myself what I would do if I do have the BRCA mutation. Looking at the bright side, there would still be a 20 to 30 percent chance that cancer would never develop. However, the odds would certainly be stacked against me. Should I, at 25 years old, consider a preventive breast or ovary removal? I have always expected to have children at some point, but considering my Aunt Karen was diagnosed in her mid-30s, I may have less than a decade to explore those options and still plan for the worst.

For some, as my doctor explained during my exam last week, knowing of these mutations can induce crippling anxiety. The related stresses, she told me, can actually carry health risks of their own.

Ever the optimist, I expect we will see even more breakthroughs in treatment of the disease in the years to come. Makari-Judson and Jerry’s colleagues are studying various life exposures that can increase or decrease cancer risk over time. Elevated insulin levels, for example, are closely linked with the disease. Researchers are still exploring the relationship, but it is thought that because exercise reduces insulin levels (in addition to a myriad of other health benefits), exercise over time can reduce one’s risk for the disease. Researchers are also looking closely at a number of agricultural chemicals for their ability to distort gene expression and lead to cancer.

Jerry explains that if you inherit a mutation, you are one of six “bridges” closer to cancer. The other five bridges can be crossed through a number of environmental factors that increase risk—with age having the greatest impact. Every time cells divide, 6 million base pairs have to replicate. Just as you can’t make 3 billion cars without some margin of error, you can’t expect that, especially as time goes on, replication errors will not happen.

“If you look across generations, that’s what makes every individual different,” Jerry says. “We all have slight variations in our DNA and that’s a good thing. It allows us to survive in different environments; maybe it allowed us to grow legs and get up and walk out of the ocean, so those are the good parts on an evolutionary scale. But for the individual, these mistakes can end up in cancer.”

In addition to informing treatment, genomic advancements are also helping oncologists treat high-risk patients preventively. Makari-Judson says that those who come to Baystate for genetic analysis and are deemed at high risk can opt to take medications like tamoxifen preemptively. Also, by developing disease portraits through the patient registry, Jerry is developing tools to enable clinicians to identify the 20 percent of patients with atypical hyperplasia, or pre-malignant lesions, who will likely develop cancer in the future.

P53, a tumor suppressor gene like BRCA, is a recurrent theme in cancer research—it is corrupted in well over half of cancers. In cases where P53 remains unaltered during disease development, impacts of other mutations (such as BRCA mutations) are diminished. There are at least 15 tumor suppressor genes that are known to have suppressing effects to varying degrees. Research of these compensatory pathways could yield revolutionary new therapies. By better understanding the pathways of resistance, researchers may be able to design a drug to stimulate that these pathways, allowing the body to compensate for the disease internally.

“It’s not the just the gene that you’re dealt in this hand of life, this card game of life,” Jerry says. “It’s not just one card that’s going to make the difference—you have to have a full hand.”

One in eight women will get breast cancer in her lifetime, but past and present breast cancer patients show that disease does not mean defeat. Cancer Connection, a non-profit organization in Northampton, is devoted to helping those with cancer find out what they need in order to heal. By providing a variety of free classes and programs for those with cancer, the organization delves into the areas of healing that occur beyond a clinic’s walls.

Cancer Connection’s executive director Betsy Neisner has struggled with ovarian cancer for 12 years and knows how to help those newly diagnosed based on her own experience. From deciding how to tell your kids you’re sick to coping with “scanxiety,” she knows everyone deals with cancer differently.

“You have to figure out what’s best for you,” Neisner says. “We help people learn how to find that out for themselves.”

Becky Jones is one of Cancer Connection’s “renaissance women.” She volunteers at the office, at the organization’s thrift store, and is on the board. Jones recalls the feeling of being diagnosed for the first time and not knowing where to turn.

“I felt incredibly vulnerable and thrown into the water and I did not know about any raft or life jackets, yet,” she says.

Wanting others to have more resources at the ready, Jones was part of the initial group that came together with the idea for Cancer Connection more than a decade ago.

Two years after diagnosis, Jennifer Graves, a close family friend who lives in Chicopee, remains the strong, beautiful women I have always known her to be. After five rounds of chemotherapy and six surgeries, including a double mastectomy and subsequent reconstruction, her spirit is undaunted and her life unaffected, save for the scars.

“The scars are still there,” she said. “But they’ll fade.”

Contact: adrane@valleyadvocate.com•