The Grand Ballroom at the Hotel Northampton was abuzz with excitement. Antiquarian booksellers and private collectors perused hundreds of rare items displayed on long tables in final preparation for the evening’s auction, picking up leatherbound books, laminated broadsides, old, flimsy chapbooks, and other ephemera.

Items to be auctioned that evening included a broadside of a verse called “The Happy Child,” dated to the early 18th century; an autograph album containing the signatures of Harriet Beecher Stowe, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Daniel Webster, Henry Wordsworth Longfellow, Artemus Ward, and others; and a copy of the Bible, written in Greek, from around 12th century.

But the big draw of the evening, if not of the entire year, was displayed by itself in the center of the room next to the auctioneer’s podium: Lot 276, the Silver-Mathews Fourth Folio Shakespeare, described as “the fourth edition of Shakespeare’s Comedies, Histories, and Tragedies,” and “the last of the 17th-century editions of Shakespeare’s collected works.”

Bidding for many of the 321 items up for auction that evening began at a relatively sober $50, though several items sold for hundreds, or thousands of dollars. But the opening bid for The Shakespeare was set at $62,000, and many of the Valley’s antiquarian booksellers told me they wouldn’t be surprised if it fetched six figures.

“I love my job,” Paul Muller-Reed said. He auctions items twice a month at the Hotel Northampton. “But this,” he nodded to the podium, “is the hardest part.”

With only a few minutes remaining before the auction, most of the 50 or so buyers had already found seats in the rows of chairs that filled up half of the ballroom. Another 50 buyers would phone in their bids from as far away as the United Kingdom. A few of the attendees sipped glasses of red wine or pints of beer. Others sat next to cardboard boxes waiting to be filled with the bounty of their successful bids. Over half the bidders were fellow booksellers, hoping to acquire antiques at a good price that they could then sell at a profit. Others were private collectors. Several represented libraries. Many of the attendees talked jovially amongst themselves. Others waited in hushed anticipation.

At the podium, Muller-Reed attached a microphone to his sport jacket, checked his watch, and took a long sip of water. A bearded man sitting in the back closed the doors to the lobby. Another man searched across the crowd for an open seat.

Muller-Reed tapped on the microphone and thanked everyone for coming. To his right, his assistant held up Lot 1: an account book from the 1830s. A woman held up her buyer number, indicating the evening’s opening bid.

“We’re an individualistic lot,” Peter L. Masi said at his shop in Montague of the Valley’s rare bookseller community at his shop in Montague. “There are as many ways to do it as there are people who do it.”

The term “shop” may be a bit of a misnomer in Masi’s case. Like many locations I visited, Masi’s space had the feel of a hidden attic, or a secret, cramped basement closet. Books packed onto shelves lined more space than seemed available. Stacks of folders and laminated printed material threatened to fall over. Every item seemed like a Pandora’s box of intrigue.

Masi, who specializes in architecture, cooking, medicine, and trade catalogues, is the president of the Southern New England Antiquarian Booksellers (SNEAB), an organization of 146 businesses in Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Massachusetts.

“It’s a volunteer trade organization for self-employed people,” Masi said.

Over the past 30 years, the Internet has created “an unbelievable buyer’s market,” he added, forcing rare booksellers to continuously evolve to changing times. These days, Masi deals mostly in ephemera.

“We live by our wits,” Masi continued. “Survival is the new getting ahead.”

Including Masi, three of the four SNEAB officers operate out of the Valley. Duane A. Stevens, of Wiggins Fine Books in Shelburne Falls, serves as vice president. Eileen Corbeil, of White Square Fine Books and Art in Easthampton, is the treasurer.

“The Valley is a mecca for booksellers,” added Masi. “New England probably has more books per capita than any other region.”

This Sunday, Oct. 12, SNEAB sponsors its 10th Annual Pioneer Valley Book and Ephemera Fair (pioneervalleybookfair.com) at Smith Vocational High School in Northampton.

“Every show is probably one dealer’s worst ever and another’s best,” Masi said. “One person won’t sell a thing, while another might clear five figures.”

He stressed that, while there are many high-end dealers in the Valley, “the majority of exhibitors at the show will be offering items in a very wide price range. Items don’t have to be expensive to be interesting or of historical value. Many of the sellers who do not attract as much attention have worthwhile stock and unusual stories to tell.”

Masi expects around 50 exhibitors, including Eugene Povirk, of Conway’s Southpaw Books, and Lin and Tucker Respess, of Northampton’s L and T Respess Books.

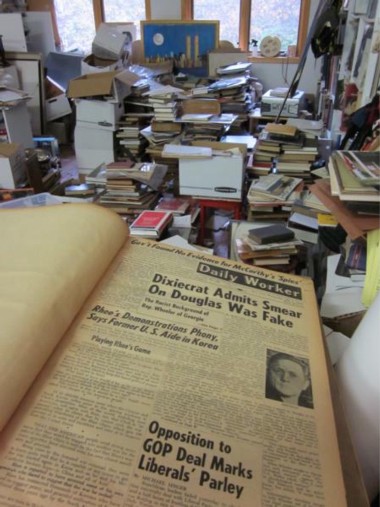

Co-owner of the Whately Antiquarian Book Center (located in Hatfield), Povirk accumulated 20,000 books in Boston in the 1980s, but moved to Western Mass. when urban rents became prohibitive. His Southpaw Books specializes in social reform, radical politics, and labor history. The two rooms above Povirk’s garage in Conway are stacked with books on wooden shelves that he built himself. There are also rare records (such as Paul Robeson reading Langston Hughes) and photographs (like one of an African-American officer from a Massachusetts regiment in the Spanish-American War), as well as old, bound issues of The Daily Worker. His garage includes old communist magazines and hundreds more books in wooden crates. Povirk also has a large photo of Che Guevera, signed on the back side to his daughter, which the bookseller hopes will help fund his retirement.

Lin and Tucker Respess began their bookselling career in 1980 in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, eventually settling in Northampton from 1989-1993, and returning in 2011. The Respesses specialize in Southern Americana, as well as hunting and fishing.

“Philadelphia, New York, and Boston were the original literary centers,” the Respesses told me as we sat in their appointment-only shop near Smith College. “The same material in the South is decidedly rarer.”

The Respesses are one of several local booksellers who also belong to the Antiquarian Booksellers Association of America (ABAA) in addition to SNEAB. Of the association’s 450 or so members nationwide, five of them are located between Amherst and Northampton, including Hadley’s Ken Lopez, who served as president of the ABAA from 2002-2004.

“The Valley is enormously rich in everything book-related, including antiquarian books,” said Lopez. “The antiquarian book market, though, is a national and even international market, so there is not necessarily a huge amount of commerce taking place within the Valley itself. Much of it involves dealers like the Respesses flying below the radar locally, but having an impact on the antiquarian book trade nationally.

“There is definitely some antiquarian activity here, though,” Lopez continued. “I sold a collection of Native American literature—some 1,700 volumes dating from the 1700s to the 2000s—to Amherst College last year. Smith College has a fine rare book library. Years ago, I sold the film critic Pauline Kael’s personal film reference library to Hampshire College. And there are definitely some individual collectors in the Valley, as there are all over the country.”

Lopez added that there is little competitive overlap among local booksellers because of their wide array of specialties. But inevitably, some does exist.

The booksellers community is relatively small, and full of “profound friendships,” Masi told me. “But we do compete. When I go to an auction, I can look at the items, and look at who’s there, and know exactly what I’ll be able to get, and what I won’t.”

With bidding on the Shakespeare stalled at $65,000, Paul Muller-Reed took a deep breath and stepped back from the podium.

“Going once… going twice… Do I have 66?”

The room was so silent you could hear a page from a 200-year-old chapbook drop.

“I have 65. Do I have 66?”

A man in the front of the room raised his hand.

“66,000. Do I have 67?”

The man in the back of the room immediately upped his bid from $65,000 to $67,000. The man in the front of the room crossed his legs and grinned nervously.

“I have 67,” Muller-Reed stated slowly, after pausing to take another long sip of water. “Do I have 68?”

The seconds ticked by like hours.

“I have 67,” he repeated, again stepping back from the podium. “Do I have 68?”

His question hung in the air, buoyed by anxious anticipation.

“Going once…

“Going twice…”

The man in the front of the room raised his hand.

“Do I have 68?” Muller-Reed said. The man nodded his head.

“I have 68. Do I have 69?” he asked, looking to the man in the back, who held up his number.

“I have 69. Do I have 70?” Muller-Reed looked to the man in the front of the room, who shook his head.

“Going once… going twice…”

After knocking on the blank white office door, I double-checked the directions Ken Lopez emailed me: off Route 9 in Hadley, up the stairs, unmarked door on the left. “You wouldn’t be the first person to phone from the parking lot if you can’t locate us,” he said.

I phoned from the parking lot.

Among the most notable book dealers in the Valley, if not the country, Lopez began his career at the Goddard College bookstore, after living “underground,” he said, for five years during the Vietnam War. He specializes in Native American literature, the ’60s, the Beats, and modern first editions.

“The best books are not only great literature,” Lopez told me as we talked in his office, “but specific copies tell specific stories as well.”

He also has paintings by e.e. cummings, William Burroughs, and Ralph Steadman. At the entrance to his office, an original Steadman print from Fear And Loathing In Las Vegas is inscribed “To Ken Lopez.”

These days archives—which Lopez usually brokers on behalf of an author’s estate—account for over half of his business. Years ago he sold N. Scott Momaday’s archives to the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University for half a million dollars, though most archives are sold for around $200,000.

As we talked, Peter Matthiessen’s archives—including not just letters and original manuscript pages, but also fishing ties and a tattered flag from Cesar Chavez’s united farmworkers movement, sat in a room down the hall. In Lopez’ office, my folded-up jacket rested on a cardboard box marked “Mario Puzo,” which included the original screenplays of The Godfather and The Godfather, Part II.

Lopez told me that the famous line “sleeps with the fishes,” originally just read “dead,” but was amended to read “dead with the fishes.”

I wondered if it was difficult for dealers, who know so much about the things they acquire, to sell such cherished items.

While Lopez said he has a bit of the “collector gene,” he considers himself a “temporary collector,” who gets to posses the items “while the flush of enjoyment is at its peak.”

“They go into the personal collection for a while,” he said, attributing the saying to a former co-worker, “and then I sell them.”

“What am I going to do with them after a few weeks?” he added.

Tucker Respess admitted she gets attached to certain items. She and her husband recently sold a series of 14 Civil War-era letters between Massachusetts congressman Samuel Hooper and his wife Anne, which detailed four private meetings Hooper had with President Abraham Lincoln.

Masi enjoys buying and selling antique books and ephemera as “a way to actively participate in history.”

After the rush of excitement from the winning bid of $69,000 on the Shakespeare, several attendees gathered up their belongings and new acquisitions and headed out the door.

I followed a thin man with a large, leatherbound volume tucked under his arm. The man walked down King Street and turned right on Main at the four-way intersection. His heavy, antique book seemed out of place among the beeping crosswalk signs and youthful nightcrawlers. The man continued with a steady gait, and disappeared into the darkness of the night.•