Two days ago I had the honor of moderating the second of this fall’s four Created Equal: Conversations on Negotiating the American Social Contract events. The series of public film and discussion forums is designed to showcase the theme of Mass Humanities’ 40th Anniversary year (Negotiating the Social Contract) and encourage community organizations and cultural institutions to imagine, propose and carry out public humanities projects of their own. Sunday’s event, held in Brockton at the recently restored War Memorial Building, brought together close to fifty community members to discuss the hard but important work of negotiating, sustaining, challenging and even transforming the social contract in a democracy. The energy in the room was palpable and the ideas flowed freely, as they did last month at the first event in Lawrence.

Two days ago I had the honor of moderating the second of this fall’s four Created Equal: Conversations on Negotiating the American Social Contract events. The series of public film and discussion forums is designed to showcase the theme of Mass Humanities’ 40th Anniversary year (Negotiating the Social Contract) and encourage community organizations and cultural institutions to imagine, propose and carry out public humanities projects of their own. Sunday’s event, held in Brockton at the recently restored War Memorial Building, brought together close to fifty community members to discuss the hard but important work of negotiating, sustaining, challenging and even transforming the social contract in a democracy. The energy in the room was palpable and the ideas flowed freely, as they did last month at the first event in Lawrence.

The discussions were motivated by selections from three impressive documentary films about the 1960s—The Loving Story, Freedom Riders and The Most Dangerous Man in America: Daniel Ellsberg and the Pentagon Papers—and are designed to engage urgent questions such as What do we owe each other? How can we deliver on the promise of equality that animates our democracy? Most centrally, the events ask attendees to consider: What does the social contract mean, who creates it, and what responsibility does each of us have to enact, police, protect or change it?

The need for such questions and the need to speak and listen to one another’s answers could not be more pressing. The ongoing tragedy of Ferguson, MO, the debates over “illegal” immigration, discussions about marriage equality, various opinions on whether Edward Snowden is a hero or a traitor, negotiations over what should be required of those who receive public benefits, the status of corporations as individuals . . . each of these issues and many more fill the evening news and provide fodder for political ads. They bubble up around water coolers and can tear families, friends, and communities apart. And yet, we cannot look away, for to look away is to abdicate our responsibility, in a democracy, to the work of caretaking the social contract. To converse around these questions is to participate in the complex and ongoing work of making and remaking a society that serves the common good.

In general terms the social contract is understood to be a set of implicit or explicit agreements about how to live together in a society or nation peacefully and constructively without relying on terror, violence or coercion. But the American ideal of social contract goes beyond this general term. The “American” social contract is often understood to be the idea that we live in a society in which we agree to equality and justice for all who are part of the body politic. The social contract that many Americans understand themselves to be living under is one in which all members of society share the same rights and share the same responsibilities to and for one another. Yet, understanding or wishing something to be so does not always mean it is so. And it is this gap between perception and experience that undergirds this fall’s events.

After all, if the social contract is not attended to, or if it is taken for granted, it can begin to break down. Rights can become the sole focus of our civic dialogue, and inequality—of opportunity, of access, of power—can emerge. Furthermore, these inequalities emerge not despite differences and diversities of views, but as a result. In a society such as ours where not only do differences exist but are both allowed and encouraged, there is a constant need to think about whether or not the social contract is being upheld and for whom?

And so, in Lawrence and Brockton to date (and in Pittsfield and Worcester in the coming days), diverse groups of citizens have gathered to think, talk, and listen. Drawing upon the insights of history and the artistry of film we’ve gathered to consider how we move forward to fulfill the promise of the social contract, how we negotiate different ideas about what is in the common good and what work needs to be done—individually, collectively, through action, through example—to safeguard, alter or thwart threats to the American social contract.

The three films featured in these public discussions are rich touchstones for our discourse. Two are part of the Created Equal initiative of NEH and the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, and the third was funded in part by Mass Humanities. Collectively they offer rich case studies to understand why individuals might challenge the existing understanding of the social contract and they offer up three different examples of how the social contract can be revised: through the legal process, through non-violent civil disobedience and through whistle-blowing. The beauty of the films is that each one draws us into a particularly intimate setting in which individuals—not so different from you or me—are faced with the reality that the social contract is broken.

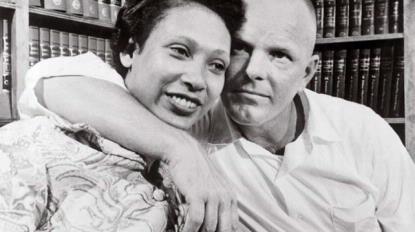

The story of Richard and Mildred Loving (The Loving Story) is a tale of quiet personal suffering that led to a Supreme Court case. The fact that two young newlyweds were jailed for marrying across defined racial lines in 1950s VA while their same-race contemporaries faced no such treatment forces us to think about who is included in the “we” of “we the people”? If the social contract is an agreed upon set of rights and responsibilities to ensure the “common good,” it matters greatly who is at the table when the social contract is being negotiated in the first place. The Loving’s ordeal is poignant reminder that the social contract is limited when the “we” is limited.

Freedom Riders ask us a different question about the social contract. As we witness the brutality and violence inflicted upon young men and women riding buses into Alabama in the spring of 1961, we come face to face with the reality that in a nation or even in a community, very different ideas of the social contract can and do coexist. For most viewers in 2014 it is hard to imagine how the white attackers on the screen could fight so hard to maintain what seems like an obvious injustice such as segregation. Yet asking and trying to answer the question “how” is precisely the hard work we did on Sunday. Not only “how” could the attackers do what they did, but “how” were so many others in the US blind to the crisis. We grappled with the idea that people can be blinded to injustice. They can be caught in “the fog of the everyday”. They can believe that the social contract they live under is the only one there is. They can believe that laws and the social contract are one and the same.

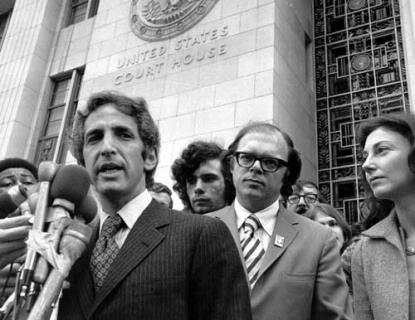

The final film of the program, The Most Dangerous Man in America, calls us to action. Or, rather, it calls us to consider what action is necessary or “right” when we sense that the social contract is under threat. Remembering that there is no single idea of “the” social contract, the film follows Daniel Ellsberg’s struggle to reconcile new ideas about the social contract emerging in the late 1960s with his earlier understanding of the social contract and his involvement in creating the secret documents that came to be known as The Pentagon Papers. In the clips we walk with him as he begins to take risks and finally releases the classified documents to The New York Times. In so doing, like the Lovings and the Freedom Riders, this man— Richard Nixon called him “the most dangerous man in America”—challenges the existing social contract in favor of an alternative. Evoking Henry David Thoreau, Ellsberg tells viewers that he did what he did because he took to heart Thoreau’s admonition to “cast your whole vote.” There was only one path forward as he saw it.

And on Sunday in Brockton as in September in Lawrence, it was Thoreau’s words that framed our final discussion. The men and women who filled red chairs in a gorgeous theatre space–some in their 20s, some in their eighties and everyone else in between— joined together to consider the social contract and found themselves grappling with the question of what it would look like today, in their daily life to “cast your whole vote”? They sat with this question in small groups as they had with other questions throughout the afternoon and struggled to find a simple answer. They struggled as we all struggle because there is no easy answer to a question about what is required of us, individually, vis a vis maintaining or challenging the social contract. There is no easy answer to the question of how to fruitfully resolve differences between various versions of the social contract.

But as attendees began to share their thoughts with the larger group, a theme emerged: listening and discussing across ideological, political and all other lines is essential. There will be differences, attendees repeatedly pointed out, but coming together to discuss is a place to begin to address them. And seeking insight and wisdom from one another as well as from history and literature and philosophy – as we did on that day – is a pretty good place to begin as well. These, the gifts of the humanities, offered encouragement to attendees and examples of how to continue the important work of negotiating this messy thing called “the social contract.”

In our own era – an era of pointed political attacks and public discourse that too often devolves into competing sound bytes or retrenchment—we are called to bring compassion and wisdom and the lessons of the past to our interactions with our friends, neighbors and co-workers. We are called to bring these to those we agree with and those we do not. The humanities – here, history and film—matter in the practical, political and daily work of a democracy. They matter because studying negotiations over the social contract in the past can help us engage in the here and now as we navigate different conceptions of the social contract in our lives and make decisions about our role in maintaining or challenging it.

Driving home from Brockton with my mother on Sunday (she had come to visit from out of state and joined me for the afternoon) the conversation continued. We asked each other additional questions and we rehashed questions from the afternoon’s event: How difficult is it to listen to those who have a different version of the social contract? How much are we willing to risk to effect change if we think the social contract is under threat? What have we done when we knew we had to do something? We talked for an hour straight and we are still talking. We are still thinking. I suspect many of the attendees are as well. I hope so.

For those who wish to join in this conversation and engage the humanities as a way to enrich and strengthen the democracy in which we live, please come join me later this week as Mass Humanities continues to celebrate 40 years of supporting and promoting the place of the humanities in the Commonwealth. Come and share your voice at one (or both) of the remaining conversations this month. We will be screening portions of films and talking on Thursday October 23 at the Berkshire Museum in Pittsfield, 7-10 PM and at the Worcester Public Library: Main Branch on Sunday October 26, 2-5 PM. Your wisdom and insight is desired.