In the later sixteenth century, about a century after the introduction of the print, Renaissance humanists evolved a novel literary genre, the Essay. The name itself was probably coined by the French thinker Michel de Montaigne. He felt he needed a written mode that would allow him to capture his own thoughts on an important subject, to test their validity, to speculate about their deeper meaning, and to accomplish all this in a fashion that both pleased his readers and instructed them. So Montaigne invented the essais, or “attempt,” from a French verb meaning “to try.” It was a very appropriate choice. For Montaigne was really trying—that’s the key word—to clarify his thoughts. His essays are steps along the road to understanding, not understanding itself. There is nothing really finished about them. They are speculative probes into the unknown, risky forays into possible worlds, brave excursions into what might be. What is said in them may be true, or it may not be true. That is really for others to decide. And that, of course, is the point: to set forth what he believes might be the case so that others may consider it. The essay is not only an exercise in exploration, but in collaboration as well.

In the later sixteenth century, about a century after the introduction of the print, Renaissance humanists evolved a novel literary genre, the Essay. The name itself was probably coined by the French thinker Michel de Montaigne. He felt he needed a written mode that would allow him to capture his own thoughts on an important subject, to test their validity, to speculate about their deeper meaning, and to accomplish all this in a fashion that both pleased his readers and instructed them. So Montaigne invented the essais, or “attempt,” from a French verb meaning “to try.” It was a very appropriate choice. For Montaigne was really trying—that’s the key word—to clarify his thoughts. His essays are steps along the road to understanding, not understanding itself. There is nothing really finished about them. They are speculative probes into the unknown, risky forays into possible worlds, brave excursions into what might be. What is said in them may be true, or it may not be true. That is really for others to decide. And that, of course, is the point: to set forth what he believes might be the case so that others may consider it. The essay is not only an exercise in exploration, but in collaboration as well.

And here we come to an important consideration. Montaigne and those essayist who followed him—Francis Bacon being first among them—knew very well that if you wanted people to think with you, you had to be brief but not too brief. Montaigne looked around him at the genres made available by print and didn’t really like what he saw. On the one hand he had books of proverbs, maxims, and aphorisms. Pithy sayings were all the rage in the Renaissance, probably because they were easy to remember and could make pretentious courtiers look smarter than they were. But they were often so short and so catchy that they stymied thought. A saying like “A stitch in time saves nine” doesn’t invite you reconsider something, but rather reinforces what “everybody” already knows. On the other hand, Montaigne had shelves full of weighty treatises, discourses, and dissertations. But these were too long to hold the interest of any but the most devoted scholar or leisured gentleman. Nobody really read them.

So the early Renaissance essayists designed a piece of writing that was not adapted to the narrow confines of human memory—like the proverb—or to the far reaches of human endurance—like the dissertation—but rather tailored to the brief but not too brief attention span of readers with a bit of spare time on their hands. Just how long “brief, but not too brief” was depended on the essayist. Bacon’s essays tend to be on the short side: his piece “Of Truth” contains just under 900 words. Montaigne’s tend to be longish: his essay “On Cannibals” runs about 6,000 words. But whether short or long, the essay was very convenient. Some could be read in a few minutes—for example, while you waited for the kettle to boil—others in an hour—the amount of time that you have before you fall asleep. The essay, in a word, “fit” who we are and life as we live it.

It’s little wonder, then, that essays became incredibly popular and still are. In fact, most of the things we read on a day-to-day basis are essays. Newspaper and magazine articles, reports and briefings, memos and letters—all of them bear the mark of the essay.

Yet it would be hard to deny that the essay is changing. And the reason is plain: the Internet. The web offers many new opportunities for people to write, publish, and read essays. You can find millions of them in online-magazines, personal blogs, and community discussion sites. But perhaps the most curious—and certainly the most novel—Internet essays are those found on video sharing sites such as YouTube. These are essays such as Montaigne and Bacon never imagined because they are not intended to be read. No, their authors want you to watch and listen to them. We should recognize them for what they are: video essays, a new, promising variation on an old form.

Some years ago I created a project with my students aimed at exploring the form and substance of the evolving video essay. We chose as our subject “Mechanical Icons”: photographs (mechanically produced) that have become symbols of things larger than themselves (icons). The photographs were chosen precisely because they are well known—you’ve probably seen most of them. This familiarity gives us—the essayist and audience—a common point of departure for our exploration. In the voiceovers, we tell you what we think the iconic photographs “mean,” that is, we rendered an interpretation. No doubt we were wrong about a lot of things, and you will justifiably disagree with some of what we have to say. But that’s really the object: to challenge you to think about these familiar objects of our collective experience, to consider and reconsider what they and the events they represent mean for our common enterprise. By drawing all these things to mind, by thinking them through, by turning them over and over again, we accomplish just what Montaigne and Bacon intended—we become more human. We hope you enjoy our essays.

Some years ago I created a project with my students aimed at exploring the form and substance of the evolving video essay. We chose as our subject “Mechanical Icons”: photographs (mechanically produced) that have become symbols of things larger than themselves (icons). The photographs were chosen precisely because they are well known—you’ve probably seen most of them. This familiarity gives us—the essayist and audience—a common point of departure for our exploration. In the voiceovers, we tell you what we think the iconic photographs “mean,” that is, we rendered an interpretation. No doubt we were wrong about a lot of things, and you will justifiably disagree with some of what we have to say. But that’s really the object: to challenge you to think about these familiar objects of our collective experience, to consider and reconsider what they and the events they represent mean for our common enterprise. By drawing all these things to mind, by thinking them through, by turning them over and over again, we accomplish just what Montaigne and Bacon intended—we become more human. We hope you enjoy our essays.

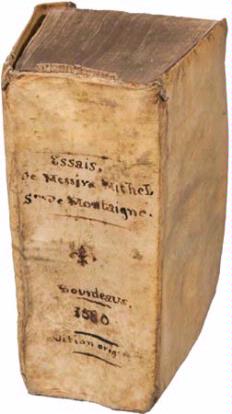

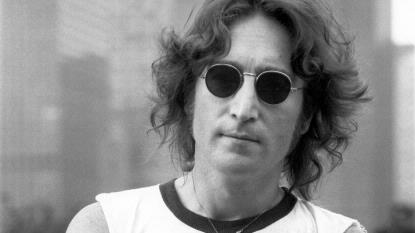

Photos, top to bottom:

First edition copy of Michel de Montaigne’s Essais (1580; Essays).

John Lennon by Bob Gruen, 1974