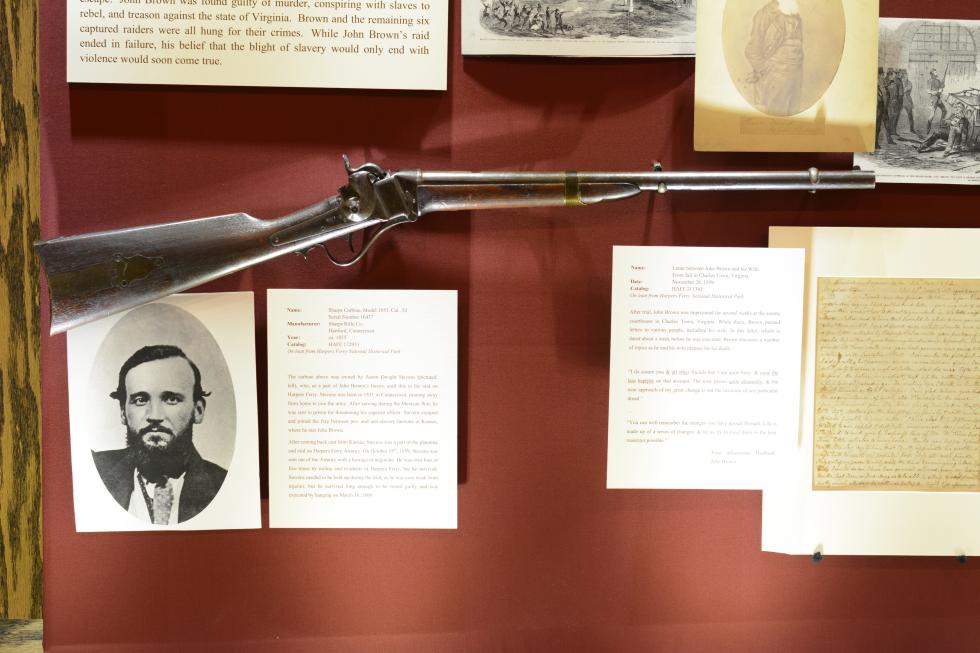

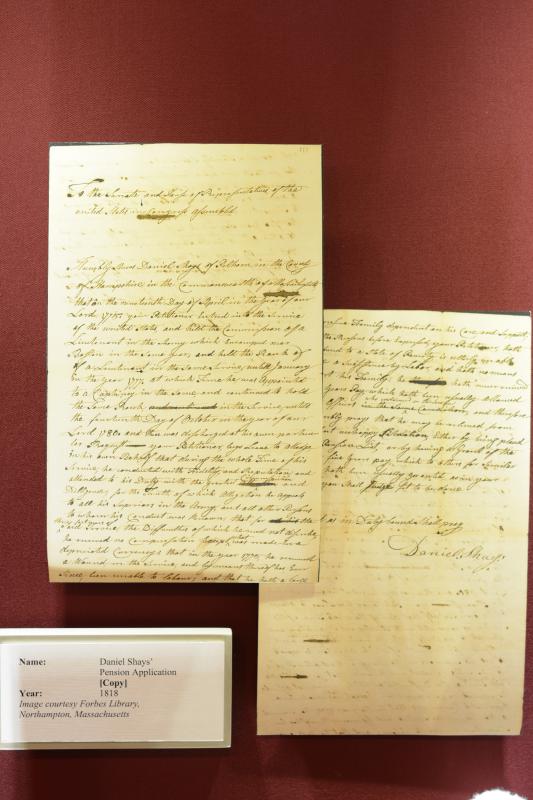

Aaron Dwight Stephens was born in Connecticut in 1831. As a young man, he ran away to join the army and served in the Mexican War — until he was sent to jail for threatening the life of an officer. Stephens escaped from prison, however, and relocated to the Kansas Territory during the violent pro- versus anti-slavery pre-Civil War era known as Bleeding Kansas. There he joined up with abolitionist John Brown. Later, Stephens traveled with Brown and his band to Harpers Ferry, Virginia (now in West Virginia) and participated in Brown’s failed attempt to take over the arsenal and end slavery in the United States by distributing weapons to slaves throughout the Appalachian Mountains. Brown and his men were famously defeated by troops led by soon-to-be Confederate war hero Colonel Robert E. Lee. Despite being shot four times during the raid, Stephens survived the battle — only to be sentenced to death by hanging. Today, the rifle Stephens used in the attack at Harpers Ferry sits behind a glass case in the Springfield Armory, part of the new exhibit Arsenals Under Attack! Daniels Shays’ Assault on Springfield and John Brown’s Raid on Harpers Ferry, which runs through March 22, 2015. “Stephens survived just long enough to get hanged,” Springfield Armory curator Alex MacKenzie tells me as we look at the glass case. Below his rifle, Stephens stares back at us from an old, black-and-white photo. Arsenals Under Attack! explores the controversy and impact of both raids, not just through objects and images, but also via period quotes responding to each event. The space in the armory occupied by the exhibit is small — a mere 250 or so square feet — but the information contains much to digest and ponder. Both present-day national historic sites, Springfield and Harpers Ferry were the two oldest armories in the country. The arsenal at Springfield was established in 1777, 10 years before Shays’ Rebellion. In 1794, it was selected by George Washington as one of the first two federal armories in the country. The other was Harpers Ferry. Both attacks, as well as the men who led them, have long been controversial. Even those sympathetic with the motivation for Shays’ rebellion (preventing the government from financially oppressing farmers and Revolutionary War veterans) and Brown’s raid (the abolition of slavery) often disagree with the violent methods both men chose. Arsenals Under Attack! embraces this incongruity. “The creation of the exhibit was a matter of good timing,” says MacKenzie. “There are clear similarities between John Brown and Daniel Shays — not least of which is the fact that they attacked what would later become two national parks — and an exhibit discussing those similarities seemed like a great topic. We were able to work with other institutions, mainly Harpers Ferry National Historical Park and the University of Massachusetts, to secure items on loan, and the exhibit just came together.” The exhibit is part of the armory’s ongoing attempt to focus on school groups. “Educators from Springfield and the surrounding communities are lining up school groups who study both Shays’ Rebellion and John Brown’s Raid in middle and high schools,” says chief of interpretation Joanne M. Gangi-Wellman. “The special exhibit is fascinating, disturbing, and encourages visitors to grapple with the actions of these passionate men who lived in Springfield and Western Massachusetts.” Shays lived in Pelham, and today Route 202 is known as the Daniel Shays Highway. Along with his band of Regulators, he made a practice of breaking folks out of debtor’s prison. But it’s surprising to hear that Brown had Western Mass. roots, too. “The Lyman and Merrie Wood Museum of Springfield History has much more information on this topic, which is fascinating,” MacKenzie says. “Brown spent time here trying to make a living as a wool merchant, though he was still involved in the anti-slavery movement with the League of Gileadites, and even hosted Frederick Douglass while living in town.” Items on display include three of the 954 spear-like pikes with which Brown intended to arm slaves, a copy (the original is at the Forbes Library in Northampton) of the letter Shays wrote to apply for his government pension — in which he failed to mention his role in the armory attack that bears his name — and a John Brown stuffed doll from the gift shop at Harpers Ferry National Historical Park. As we walk through the exhibit, MacKenzie points to an anti-Shays’ Rebellion broadsheet that was created by then-Massachusetts governor James Bowdoin. Following its publication, MacKenzie notes, Bowdoin lost his re-election bid to John Hancock. On the wall behind the glass case containing the broadsheet are a series of quotes, both supportive and critical of Shays’ Rebellion. The same kind of display is repeated for Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry. In both cases, it’s interesting to note who was on which side. “God forbid that we should ever be 20 years without such a rebellion,” Thomas Jefferson famously said in response to Shays’ attack on the Springfield Armory. “The tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants. It is natural manure.” But Ben Franklin and Abigail Adams weren’t so sure. Neither was Samuel Adams, who supported rebelling against a monarchy, “but the man who dares rebel against the laws of the republic,” the display quotes, “ought to suffer death.” Shays’ Rebellion, the exhibit notes, reawakened class tensions and divisions that had existed since the Revolution. “Historian Leonard Richards called Shays’ Rebellion ‘the last battle of the Revolution.’ Mainly, a lot of the poorer classes — many of whom fought in the Revolution — didn’t realize the promise of an independent America until the country was reorganized under the Constitution,” MacKenzie says. “Shays’ Rebellion called attention to these issues, and affected the way the Constitution was crafted in 1787, shortly after the battle at the Springfield Arsenal.” Reactions to the raid at Harpers Ferry were similarly divisive. While the display shows support from influential voices such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, several daily newspapers were quite critical. “If there were any Abolitionists silly enough to take part in such an affair,” the Hartford Daily Courant wrote in October, 1859, “we devoutly hope they were most of them killed in the act.” But regardless of the reactions to the rebellions then and now, each raid left its mark on history, and the causes which fueled them were eventually successful. “Each attack failed. Neither Brown nor Shays were able to successfully take their immediate objectives, which were the weaponry in storage at each place that would assist in their larger cause. However, their overall goals,” MacKenzie says, “were ultimately achieved through the creation of the Constitution and later amendments.”•