When Massachusetts Attorney General-elect Maura Healey takes office on Wednesday Jan. 21, she will become the chief law enforcement officer of a state in which heroin, opioid, and prescription drug addiction has been sharply on the rise for over a decade.

Last March, Gov. Deval Patrick declared drug addiction in Massachusetts a public health emergency, saying that opiate overdoses in the state rose 90 percent between 2000 and 2012. In 2012, the overdose rate reached 10.1 deaths per 100,000 residents. Earlier this month, Healey announced the creation of a task force within the attorney general’s office to devote fresh time and energy to tackling the growing epidemic.

Her plan, which she detailed during her campaign, is multi-pronged. She wants better real-time monitoring of prescription histories by physicians and more police on the ground at drug trafficking hotspots. She supports the pharmacy lock-in program used by 46 other states, in which those suspected of misusing prescriptions must get them through a single pharmacy and prescriber. She is advocating for reforms to the criminal justice system, more beds and services for substance abuse programs, and increased education programs for medical students, prescribers, school children, and the public.

Healey’s centralized task force will study data, analysis and comments from local health care workers, ER staff, physicians, teachers, counselors, and law enforcement officials. Then, of course, there are all the meetings to be had about how to find sustainable funding models for her plan.

That new task force won’t be the only one focused on these statewide troubles. The Opioid Task Force of Franklin County & the North Quabbin Region, for one, has been elbows-deep in these issues since it formed in September 2013.

The Advocate spoke with several key Valley players to draw some distinctions between the strategies that are working well and those that need improvement, as well as a few complications that Healey has not yet addressed in detail, such as the rising costs of the medication Narcan.

Franklin County’s opioid task force was only a few months old when Marisa Hebble came on board as the program’s lead coordinator last April. Hebble said she was wowed by the turnout at the first few task force meetings, which were hosted by Greenfield Community College.

“Interest in solving these problems has exploded,” she said. “Everyone in our communities is affected by them in some way, and there is so much pent-up feeling about it.”

Addressing drug addiction has to happen on four levels, Hebble said: prevention, intervention, treatment, and recovery. This calls for what she termed “collective impact” across many fields. “If only hospitals took this on, or only clinics, or only the police, we wouldn’t be able to make real change.”

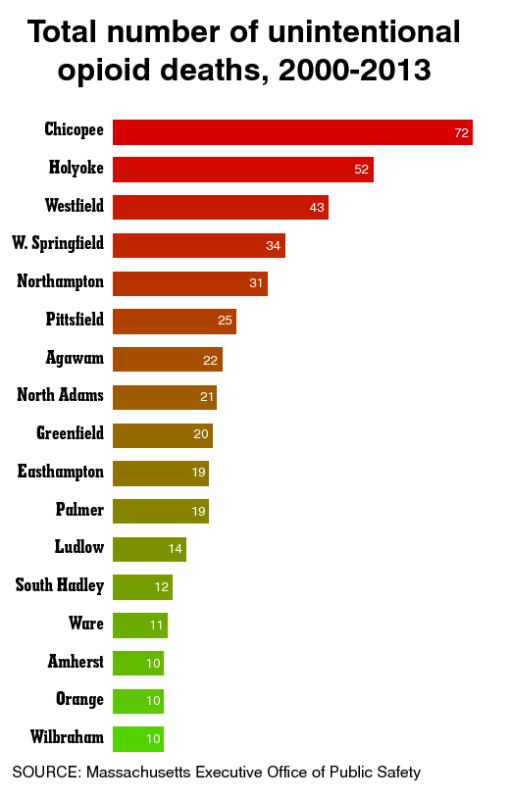

During a campaign stop in Greenfield in mid-October, Healey met with Hebble and her colleagues to discuss the task force’s working relationships with courts, schools, clinics, families, hospitals, and law enforcement. During that talk, Hebble mapped out some key trends over the past 10 years, including regional opiate overdose rates, prescribing rates per capita broken down by town, and the rise in statewide hospital admissions for abuse of opioids.

“We’re a very data-driven task force, and I think it was pretty enlightening for her,” Hebble said. Healey’s continued emphasis on combating opioid abuse is encouraging, she added. “Grassroots involvement is crucial, but all of it is bolstered by state leaders investing time and resources in this.”

Amanda Wilson, the CEO of the Massachusetts-based outpatient addiction treatment organization Clean Slate, is a member of the Franklin County task force. Healey’s push for an internal task force is “honorable,” she said, but it will only yield results if Healey collaborates on the local level.

And still the problem grows. Since Clean Slate was founded in 2009, Wilson said, the company’s 10 regional centers have taken in addicts ranging in age from 16 to 80.

“Every person I talk to seems to have one degree of separation from someone who is using. It’s that prevalent now,” she said, reiterating the need to consider this a public health issue. “If the number of deaths from, say, tuberculosis were skyrocketing at this rate, everyone would be panicked.”

The challenges in combating opioid addiction never get any less complex. For one thing, quantifying the problem is difficult, explained Hebble. People don’t typically volunteer information about their addictions.

“It’s been the hardest population we’ve had to track in all the years I’ve been here,” said John Merrigan, Franklin County’s Register of Probate and a co-founder of the Franklin County task force. “This is a new beast,” he said. “We’re not going to arrest our way out of this.”

For those addicts caught up in the criminal justice system, there need to be clear pathways to getting medical help, Hebble said. That means tightening the gaps in communication between law enforcement and health service providers.

The more an addict cycles back repeatedly through the courts without ongoing treatment, Merrigan said, the more it costs the taxpayer, and the harder it becomes for the addict to recover.

When it comes to connecting addicts with treatment for the first time, Hebble also sees promise in a new screening program currently in development at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield. It’s called Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment, or SBIRT. It is, Hebble explained, a universal substance abuse screening administered to every new patient. If a healthcare professional determines that a patient shows signs of risky substance use behaviors, they can initiate a brief conversation to provide advice and feedback on the topic, followed by a referral for those in need of additional treatment.

Other hurdles to treatment are less tangible. One, Merrigan said, is the stigma attached to drug addiction.

“We need to help people come forward. When you get referred to as an addict, or a junkie, or a loser, you tend to clam up and hide.”

Keeping policy makers focused on treatment, said Wilson, can also be difficult. “I hear a lot of ideas from drug court officials and the police about how to prevent the drugs from getting out there in the first place. But that won’t help the people who are already dependent.”

The more patients are engaged in their care, she added, the less likely they are to relapse. “You can give a patient all the medication and counseling they need, but if they’re homeless, or they don’t have the means to get back to the clinic, that’s another set of barriers to success.”

Increasing public access to the medication naloxone, Hebble said, would help tremendously. Marketed under the trade name Narcan, the medication counters the effects of opioid overdose.

“We need to get Narcan into the hands of friends and family and active users,” she said. “Anything that puts a barrier in front of getting people Narcan is not a positive thing.”

One of Healy’s goals, which Hebble shares, is to get Narcan on a statewide standing order at pharmacies, which would allow someone to walk in and get it without a prescription.

More and more police, firefighters, and first responders carry Narcan. But the cost of the medication has been going up over the past couple of years. Amphastar Pharmaceuticals now charges about $80 for a single two-ounce pack of the nasal spray, compared with an average price of $45 in previous years.

During her visit to Greenfield last year, Healey told the Franklin County task force that she would look into this rise in cost, calling it “ridiculous.” But confronting a company like Amphastar may prove to be a battle unto itself, said David Sullivan, Northwestern District Attorney and another co-founder of the local task force. Sullivan wants to see Healey and others place more focus on the role that pharmaceutical companies play in the expansion of addiction to prescription drugs.

“You have to hold these companies accountable for their sales and marketing,” he said. “Americans are prescribed such an incredibly large number of drugs. It’s not that we have more pain to treat than anyone else. It’s that opioids have become the first option we look to as opposed to the last.”•

Hunter Styles can be reached at valleyadvocate.com