Kamil Peters steps away from his metal shop to lead me on a walk through 17,000 square feet of new working space. He saunters from room to room in a cavernous old industrial mill building along the canal in Holyoke, pointing out the work spaces for artists: an oil painter and a printmaker here, a glass blower and a jewelry maker there, and rooms around the next corner for photography, horticulture, commercial products design — even creative cement pouring.

Together they make up the BRICK Coworkshop, a collaborative working space now in its second year of operations at Wauregan Building 1 on Dwight Street.

“It was divine intervention that 12 local people all needed new shops to do their work right at the same time,” he says. “We really run the gamut in here.”

Peters, 35, is a metal artist and sculptor whose commercial work can be seen all over Northampton and Amherst — he created the exterior signs for Hinge, The Dirty Truth, High Horse, The Moan & Dove, Mission Cantina, and others — and he says the work is never-ending. At least he hopes so.

“There’s no 401K when you’re an artist,” he says. “I may get a big job here and there, but even so, everything is paying for the present. You can squirrel away some savings here and there, but then you need a new power saw.”

Peters grew up in Amherst and lives there now with his wife and his son, who is almost three. BRICK was his brainchild, the manifestation of his need for a full-sized professional workspace. So far, he says, it feels perfect.

“You get in here, you clean it up, and you see how a good facility can provide for people. Now I can bring people in here. I feel like a business.”

This space contains endless possibilities, and so does Peters. He’s a creative entrepreneur: resilient during the shaky years following the 2008 recession and willing to embrace off-the-wall ideas — like BRICK — in order to evolve his business. His is one in a series of stories we’ve collected to look at how artists design their lifestyles to overcome the difficulties of rising rent and property costs, limited availability of space, unpredictable funding, and competitive urban markets.

Adaptability allows artists in the area, and everywhere, to strive for that undying dream: to sustain oneself through one’s art. But in order to put food on the table, you first have to frame your work in a professional way, says Seth Lepore, co-creator of the communal workspace Co.Lab in Easthampton.

Lepore is a performing artist who says he spend “about 86 percent” of his time doing arts administration. It is a community and workspace for anyone from novelists and graphic designers to computer programmers and translators — which is why he feels less confident sticking the label “creative” or “artist” on people these days. Those categories, he says, are getting really blurry as the Internet and technology continue to change how ambitious young people with new ideas distribute their work and sell their skills.

“I feel very strongly that artists have to be entrepreneurs,” he says. “If someone just wants to make art all day, cool. But if they actually want to make money, they have to get the skills, or they’re fucked.”

Lepore just wrote an article on this topic for the performing arts website Howlround, and he tours a workshop called “The Nuts and Bolts of Being a Performing Artist.” Making the business argument to artists hits a nerve, he says, in part because of a dearth of career conversations within arts programs at colleges and universities.

“Some teachers have never been outside the school environment,” he says, “and when you have all these resources around you, you don’t realize that you’re churning out the future waitstaff of America. If you tell a student they’re great and they’ll do well, and then they go out into the real world and get discouraged in five or 10 years, that’s not okay.”

According to the U.S. Census, the number of Valley professionals reporting their occupation as “artist” rose between 2001 and 2013 in most towns and cities. The number of reported artists employed in Northampton rose from 2,027 to 2,136 during this time. In Easthampton the count rose from 334 to 464, and Amherst saw the largest increase: from 1,257 to 2,113. The only local area to see a decrease was Holyoke, which reported a drop from 1,890 to 1,732 working artists.

Peters’ tour of the BRICK space leads us back around to his metal shop, where he leans against a rack of cut steel and tells me about his biggest recent professional hurdle: the lack of affordable workspace in the Valley for artisans like him.

All conversations among artists seem to return at some point to this quandary. To borrow a phrase from Bill Clinton: “It’s the rent, stupid.”

“If Amherst could harness us, or Northampton, we might be there instead of Holyoke,” he said. “But it’s close to impossible.”

Certain commercial buildings could handle the manufacturing work he needs to do but are cost-prohibitive. Peters is happy to be working in Holyoke right now, where the space is plentiful and the rent is much lower. BRICK pays about five dollars per square foot to rent the space, compared to locations Peters says he scouted in Northampton, Easthampton, and Amherst, which were charging three to four times that much.

“Even when I’m getting big jobs, why would I want to spend much more to work in Northampton?” he asks. “Just so I can say I’m a Northampton artist?”

Side work helps Peters pay the bills — he is a shop manager at Hampshire College, where he got his B.A., and he also works construction and odd jobs. And though he has five metalsmithing commissions lined up right now — plus a possible chance to exhibit some of his artwork at a New York gallery this summer — he still describes his work life as “sustaining by multitasking.”

Occasional money from local gigs is great, he explains, but a steady income would come from selling art pieces in New York. That’s the market he’s been trying to break into over the past six months.

He points to one wall, where he has hung 38 custom-made metal masks. That wall has about $25,000 worth of stock hanging on it — it just needs a market.

“When I go through Amherst and Northampton, I see my stuff everywhere,” he says. “But how many businesses are going to ask me to make them a sign? I’m not getting rich from that. I’m still broke as shit. Diapers are expensive.”

Rising costs of living are also driving young artists to Easthampton, where rent is cheaper and many industrial mill buildings resemble the expansive real estate in Holyoke.

The best-known among those rescued mill buildings is Eastworks on Pleasant Street, where about 100 artists and commercial clients rent work spaces and studios. These artists — some of whom have been in the building since it opened in 1997 — make fine art, jewelry, clothing, books, and various other products to support themselves, says Kim Carlino, a resident artist and administrator at Eastworks.

“Some artists here make their income from their work, and some don’t,” she says. “It’s really, really challenging nowadays to make your living from selling work, especially locally.” Many of the artists who do sell their work, she adds, have galleries in Boston and New York. Other make money by traveling around the country selling at craft fairs.

Professional artists have to do everything themselves, from marketing and self-promoting to accounting, Carlino says. “And it’s hard not to get caught up in that self-generated momentum of putting your work out there and selling.”

That’s why it’s important, to Carlino’s mind, for an artist to not put pressure on their work to be their sole income. “There’s a balance to find between working enough so that you have enough to live on, but also enough time to make work and do projects and collaborate. I’m constantly struggling with that, and it’s a tricky thing for people right now.” Carlino wishes there were more flexible spaces available where artists could do performances and pop-up events, especially in Northampton. Still, she says she would recommend this area to most young artists seeking a home. She remembers finding space to curate a project called The Laboratory, which involved 23 artists. “I would never have been able to do that in New York. Those are opportunities that you can only negotiate in smaller towns.”

Carlino takes me on a walk through Eastworks, and we end up in a design studio run by metalsmith and jewelry maker Heather Beck. The past two years in Eastworks helped lay the groundwork for her business, says Beck, as she stands and pours water and coin-shaped metal discs from a rock tumbler.

Now she works almost entirely on commission, much of which comes from word of mouth. And a growing number of new projects come from Instagram, she says. She posts “process shots” to tease a final product — a necklace, for example — and her followers online get in touch with her to request their own custom work.

“I have more work than I know what to do with,” she says. “It’s coming out my ears. That’s new. It’s really awesome.” Beck is 31, and she is excited that her primary income now comes from commissions rather than from her bartending job. A big chunk of her income also comes from teaching, she says — she leads a 10-week metalsmithing class here for adults, which costs $710 per student. Most pay on an installment plan, which provides steady income.

“To see the economy sustain entrepreneurs now, coming up after that huge crash, is amazing,” she says. “So, to be able to live my dream this way … pushing towards full-time is huge for me.”

Beck has found a business model that works for her, but some artists find that it’s possible only to plan a few months ahead. Carlino put me in touch with another recent Eastworks tenant: Esther White, an artist and event organizer who owns a small publishing house called Sister Sister Books. Last fall, White helped to curate a three-month program in the building called the Fugitive Arts Project, which hosted a dozen events showcasing experimental artwork.

The main reason that project was temporary was because of funding, she says. “We had a particular amount of money and we spent it.” Although the project was a success, she says, it could only go on for so long without anyone getting paid.

After a project in May, the future isn’t entirely clear to White, who is 29 and owns a house in Northampton with her husband and their three-month-old. She is also a board member for the Northampton Arts Council. Her husband, who works as a computer programmer, currently covers the family’s expenses.

Northampton has the resources to host finished art projects — in spaces like the APE Gallery on Main Street, for instance — but White says she sees Easthampton as the better incubator for projects being built from the ground up.

Case in point: her work with a Northampton project called Headquarters, which ran an event space and gallery out of a storage unit on Hawley Street a few years ago. Events were attended well during their year and a half there, she says, but then they couldn’t afford to pay the rental costs anymore.

“Something like that should happen again in Northampton,” she says. “It’s all so walkable. Having alternative arts spaces close to downtown would really activate the city in a way that I would love to see.”

For the most part, White says she makes work without thinking about how she is going to sell it. She sees her bookmaking and textile art as less commercial than other endeavors, such as when she made and sold T-shirts last year. Recently she has been taking some crowdfunding and PR workshops.

“I have two ideals: that art should be accessible, and that artists should be paid for their work,” she said. “It’s a symptom of our economic system that there’s a contradiction there. I don’t have an easy answer for how to fix that on a local level, but it’s something I think about often.” That’s why small publishing appeals to White. “When I make a book, that’s art that anyone can own for five dollars. That’s wonderful.”

Local sales play a key role in many Valley artists’ careers, but some steer clear.

Silas Kopf, a 65-year-old Easthampton woodworker, says he has no local clients at all.

Kopf moved to the area in 1978. He lives in Northampton and has a studio in the former Easthampton fire house, where he does marquetry work on furniture pieces. He is represented by Gallery Henoch in Chelsea, and he says a proximity to New York is part of the reason he’s remained in this area.

A self-professed cheerleader of the Easthampton arts scene and a former participant in local craft fairs like the Paradise City Art Festival, Kopf gravitated over time toward making larger, more elaborate objects. Eventually, he priced himself out of the craft fair market.

Selling art objects, no matter what they are, is not easy, he says. His pieces are now expensive to the point that a local community can’t support him, and that requires “casting a wide net” in hopes of attracting buyers on the national market.

Cassandra Kellam, a 27-year-old ceramics artist based in Florence, is also focusing on clients in New York, although she says she would like to exhibit more locally. Kellam, who works out of a studio in the Arts and Industry building on Pine Street, is putting most of her energy toward one client: a graphic design firm in Brooklyn that creates prototypes of art objects, such as flower vases, on a 3D printer. The group sends Kellam the prototypes. She makes molds, then produces them in clay.

“Right now this is how I make all my money,” she says. “I support myself on this, and I’m learning a ton doing it.”

Her income goes up and down — “I’ve made six grand one month and then two hundred dollars the next month” — but she’s gathering clients and spreading her name around. Financial stability is the goal. Until then: “I’m always here, except when I’m sleeping.”

Kellam says she would like to license her own designs to a company like Crate and Barrel someday, which is why she’s looking into taking a computer modeling class. “I hate using computers,” she says, “but I want to be the most valuable person for this work that I can be.”

She describes the Valley artist community as supportive — for better or worse, “like a mother that doesn’t want to let their kids leave for college” — but she says that TLC helped her settle quickly when she arrived in 2013. The main thing that’s missing, she says, is a culture of artists gathering just to shoot the breeze, salon-style.

“Those art conversations are always needed,” she says. “But you have to get people together who want to talk. Anything true can’t be forced.”

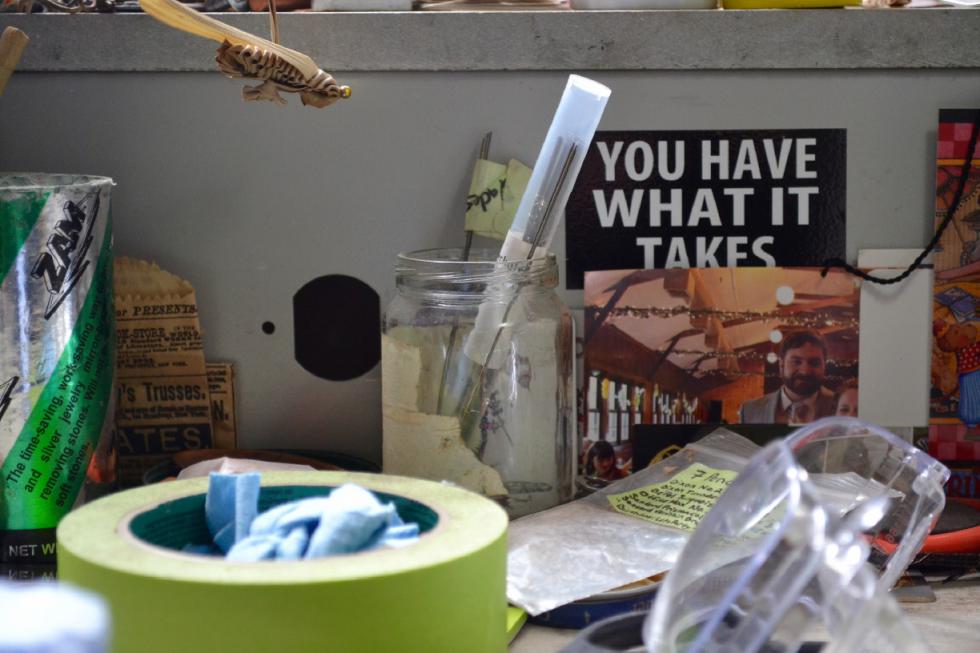

At the BRICK Coworkshop, Peters flips through images of his work on an iPad. “Everything I make is art,” he says. “Doesn’t matter who it’s for.” He shows me a long ornate railing, installed along the upper level of a private home. “She wanted it to look like the four seasons. See? So I’m hammering out all these ferns and flowers.”

He flips to another image. “Bar taps at the High Horse. Looks like a Viking ship.” He flips to an outdoor sculpture of a giraffe. “That’s Pablo. Eleven feet of propane tanks.” The next image is of an enormous steel tuna fish. “This guy from New York wanted it. Who knows what someone’s gonna ask you for?”

Such a wide range of commissions, many of them large objects, prompted Peters to seek out a workspace this big. But places of craft should be places of learning too, he says, which is why he’s looking to bring groups of young people into this space more often to learn about math, science, and history through hands-on instruction.

Peters just hosted a group visiting from the North Star learning center in Hadley, as well as 35 kids from Holyoke High School. He’s optimistic about the shop’s capacity to provide some alternative learning.

“A student that comes through my space might not become a metal sculptor,” he says. “I’m just trying to tell them that they can do this if they want to. Mostly kids get told what they can’t do. That’s what they get told in school — to settle. In high school they told me I’d make a good janitor.”

Peters raises his eyebrows, throws his arms up, and gestures to his shop. His implication is clear: a strong, simple belief in what you’re good at will take you far.

These days, he is watching for leaks in the ceiling. He’s trying to stay warm in a building without heat. He’s taken a big financial hit so far — here, the first and last month’s rent plus a non-refundable security deposit isn’t small change. But day to day, every artist here is getting by.

“I’m not trying to change the world,” Peters says. “Maybe if this were a money printing factory. But it’s not. It’s just us, and we work hard, and we’re trying to do something good.”•

Contact Hunter Styles at hstyles@valleyadvocate.com