On a recent Saturday, I stared out an airport window at an Airbus 330, emblazoned with green and the Aer Lingus shamrock. For the first time in a long time, I was staring at a plane I was about to get on. I did a lot of work to get there. Still, it was a moment of commitment a lot like steadying oneself to jump from a crane with a bungee cord attached. So yeah, no drama.

Fear of flying — a very common phobia, affecting as many as one in three people — is, like most phobias, tough to cure. Unlike most phobias, it comes with a massive hurdle most of us can’t avoid, one which makes it even harder to cure. If you’re afraid of, say, heights, you can take advantage of exposure-based therapy, in which you expose yourself to ever-increasing heights. Start with a step-stool, work up to skyscrapers over a long time.

But flying? Unless you have access to loads of cash and your own airport, you’re probably going to have a tough time going to a boarding area, then sitting on a parked airliner, then taxiing in an airliner without taking off, and so on. Even if you manage that, there’s still something irrevocable about taking flight — once the wheels leave the ground, you have to go up for a while to come back down. It’s such a leap that a lot of people just can’t manage to make it.

Even virtual reality exposure is just that — virtual. The real thing is qualitatively different.

So what’s a white-knuckler to do?

There’s always talk therapy, a pretty major commitment of its own. You can talk for years about how it feels to commit yourself to an airborne metal tube, wax eloquent about the tsunami of terror evoked by the shutting of the boarding door. And at the end of it, you might still find yourself white-knuckled in a chair in a boarding area, unable to step foot on a plane.

If you’ve been particularly traumatized by an airborne experience, EMDR (eye movement desensitization and reprogramming) is an oft-recommended treatment methodology. A lot of folks have reported success with the method in dealing with such tough-to-address matters as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. All the same, even if you’ve been freed of some of the effects of trauma, that doesn’t automatically translate to freedom from phobia, since it’s about reaction in the moment. And again, launching into thin air can be a rough way to test one’s success. Failure ain’t pretty, and it’s hard to get partially on an airplane.

I like to travel. I’ve been to Europe many times, even worked there for a couple of brief stretches. I wasn’t willing to never go back. So I made getting rid of my flight phobia a mission. I talked to experts, and I gave several methods a try. Some bore obvious fruit — I even got rid of some of the jarring effects of a true near-disaster I experienced in a small plane. Still, nothing convinced me I was ready to really step over the threshold from jetway to actual jet.

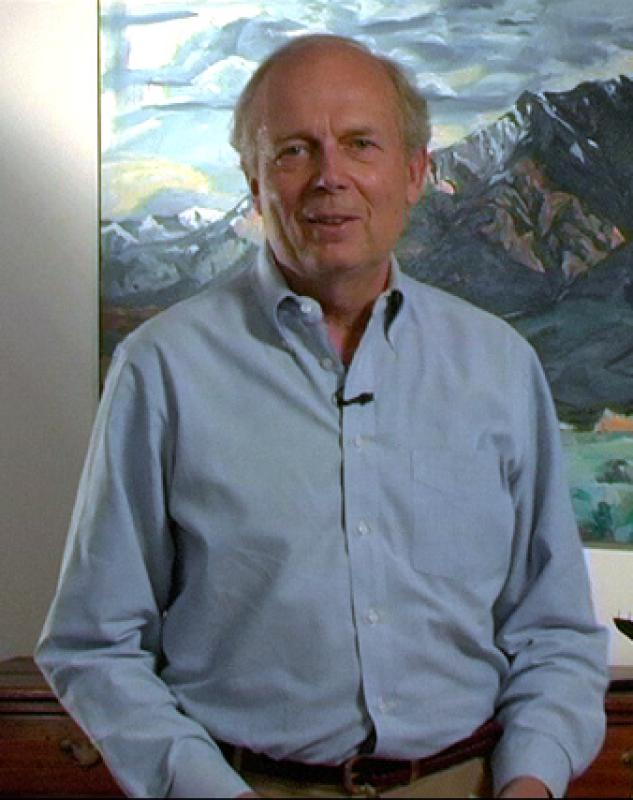

For me, the final push onto the Airbus came courtesy of Tom Bunn, former airline captain, psychologist, and head of the SOAR fear of flying program. Bunn has spent 30-plus years trying to develop the best possible method of treatment for flying phobia. His studies brought him to an unusual approach — in short, short-circuiting the amygdalae, which are more or less the brain’s alarm centers. For phobic flyers, they’re more alarmist than merely alarm. When something frightening or just out of the ordinary happens, the amygdalae deliver a jolt of stress hormones, putting us on high alert. Most of the time, we figure out that what’s happening isn’t dangerous, and the hormones subside.

It’s a tough slog to counteract an alarmist amygdala. But Bunn’s clients are often successful, and he’s become a go-to expert on fear of flying as a result.

Most people, Bunn says, don’t really know what’s going on internally when they fly — the regulation of stress hormones just happens automatically. An anxious flyer, on the other hand, is thinking about how to control the perceived threat. “In the air you don’t have anything you can do,” Bunn says. “On the ground, your backup is escape. In the air, you can’t do that, either. If you don’t have automatic calming, you don’t have much possibility to control the situation. There are two main troublesome times — turbulence and takeoff. They’re one shot of stress hormones after another.”

Bunn says that many of the usual approaches — things like breathing and relaxation exercises — just aren’t sufficient to counteract the build-up of so many jolts of stress. Panic is eventually just one bump, noise, or frightening thought away. Bunn also doesn’t recommend the preferred poison of many an anxious flyer: Xanax. That anti-anxiety medication can, for some, blunt the effects of being aboard a plane, but Bunn says it has an additional, quite detrimental effect. Use it, and you don’t gain experience with the reality of flying. Fly with it and then without it, and Bunn says your panic might well be even worse.

Bunn instead touts what he calls “the Strengthening Exercise.” It’s an attempt to circumvent the over-reactive amygdala enjoyed by fearful flyers. Instead of counteracting stress hormones, Bunn’s method aims to prevent their release in the first place. There are times when the amygdala’s reactivity is short-circuited, times when, via romance or empathic connection, our guard is totally down. Link flying with those moments, and the amygdala never gets the “panic” message. Regulation becomes automatic, a matter of preparation, not in-the-moment coping.

That’s not all there is to Bunn’s approach — he augments it with in-depth knowledge of aviation, with disarming visualizations of turbulence and other flight occurrences, and with a rather extraordinary level of personal availability to his clients. He’s also a big proponent of a surprisingly simple addition to all of that: meeting the pilots.

That offers, he explains, “a sense of control by proxy,” and a sense of the pilots’ competence. “We sense whether or not we are safe with another person both via conscious assessment of the person and by signals the person unconsciously transmits and we unconsciously receive,” Bunn adds. “The signals indicate whether we are physically safe with the person. If we sense that we are physically safe, the vagus nerve is stimulated, slowing the heart rate and activating the parasympathetic — the calming — nervous system. This overrides to some degree the stress hormones, setting aside the urge to run or fight.”

Bunn’s Strengthening Exercise felt right to me, like an approach that might actually get me on a plane. I tried several methods to uproot my phobia, so I can’t say for sure if any one thing alone did the trick. But on that recent Saturday, the boarding call came, and I switched off a video of Capt. Bunn on my phone. I’d brought his method with me, gone all in. I grabbed my bags and rolled onto the jetway.

A most curious thing happened. What had before seemed like a walk to a firing squad was just a stroll down a metal hallway. Stepping on the plane felt like stepping into my own living room. The shutting of the door — occasion for brain-splitting angst in days past — had no effect at all. Taking off didn’t even increase my heart rate. Bunn’s Strengthening Exercise seemed to have done its job.

As I watched the tops of the clouds fall ever farther behind, I couldn’t help but smile. I was a hard case. I stayed out of the air for years. But here I was, calmly sipping seltzer at 32,000 feet, heading to Ireland. All that work, finally, paid off.

It’s a thorny problem, flying phobia. It doesn’t go to bed quietly, but now I know: it can be beaten.•