There’s something strange happening on college campuses here and across the nation. Reports of rape and sexual assault are skyrocketing.

In 2013 the University of Massachusetts Amherst — a campus of 28,635 students this year — reported 22 forcible sex offenses, according to data collected by the Department of Education. That same year, the much smaller Hampshire College — a campus of 1,400 students this year — reported nearly the same number of cases: 20.

At first glance, it may seem that Hampshire’s rate of sexual assault is scary-high. But no reasonable person would conclude that Hampshire students are 18 times more likely to commit forcible sex offenses than students at UMass. What is revealed here, powerfully, is a difference in the culture of reporting.

Nationally, the rate of reported sexual assaults is going up. And thank goodness it finally is.

A report from the Department of Education, released by US Senator Barbara Boxer’s office on May 5, shows that the number of reported sex offenses at American colleges nearly doubled over a five-year period — up from 3,357 in 2009 to 6,073 in 2013. And it looks like the rate of reporting will continue to climb. In late February, a bipartisan group of senators in Congress reintroduced the Campus Accountability and Safety Act, which would require universities and colleges to publish the results of anonymous surveys on rates of sexual assault.

This legislation is an attempt to inject some hard numbers into the national conversation about student safety and sexual violence. And it’s about time, said Jordan Perry, the Director of Wellness Promotion at Hampshire College.

Perry is encouraged by Hampshire’s rising rate of reported sexual assaults. “I want to encourage people to think of this as a good thing,” she said. “The better we are at reporting, the more we can support survivors and hold perpetrators accountable.”

Perry estimates that between 20 and 25 percent of women experience some form of sexual violence in college. “When a school has a small number of reports, it’s easy to not see it as a problem,” she said. “But the reporting rate should be much, much higher to reflect what’s really going on.”

This is a critical issue in the Five College area. In 2012, former Amherst College student Angie Epifano submitted a letter to the school newspaper detailing her sexual assault at the hands of another student. And on March 30 of this year, a jury found UMass student Emmanuel T. Bile Jr. guilty of two counts of aggravated gang rape of a student in her dorm room. Bile is the first of four men to be tried on these charges.

Schools across the country are putting new programs in place to encourage reporting and bolster student safety. But do programs that raise awareness really make students feel safer? Do students feel that their schools are doing enough to protect them? What are the limits to an administration’s ability to prevent violence?

The hurdles are larger at a school the size of UMass Amherst. That’s why the university needs to provide students with information on sexual assault constantly, said Becky Lockwood, an associate director at the Center for Women and Community on campus.

“There’s room for improvement,” she said. “We need to find a way to reach out to every student, every year, over and over again, in as many ways as possible.”

To Lockwood’s mind, that would mean longer and more detailed discussions at orientation for freshmen and transfer students. It would mean more year-round, campus-wide emails on the topic. It would mean increased visibility of campus resources in residence halls, among students groups, and in certain conversations with faculty. And it would mean educating students and parents about Title IX, the 1972 federal law mandating that educational institutions condemn sex-based discrimination.

At UMass, a comprehensive plan is still being developed, said Lockwood, but it is a challenge to reach every student. “Certain groups are more likely to know about reporting and survivor support,” she said, “like student athletes and members of student government. But there’s a less clear plan for the other groups of students, who are just going to class and living their UMass life.”

We talked to a handful of those students. Some were on their way to class, while others were lounging on the grass or chatting in study groups.

Freshman Corey Shore said she has noticed some posters and university-run discussions, as well as some student activism, although she couldn’t speak about it in detail. “I know there are people on campus who are bringing about awareness, so that everyone is smarter about it,” she said.

Mei Li Dzindolet, a sophomore, has noticed bulletin boards in each dorm building detailing resources for sexual assault survivors. “I think students and RAs make those, not the school,” she said.

Sophomore Abby Williams offered a concrete suggestion to improve student safety: several campus street-lamps around her Honors College dorm are burnt out, creating dark spots in the heavily trafficked area. “Those few I’m thinking of have been broken for a few semesters now.”

Her friend Krystan Norris, a junior, nodded. “The university has a lot of money. How much money does it take to screw in a few light bulbs?”

Brendan Hoffses, a UMass senior, said he feels that there is not enough conversation happening about sexual assault. “It’s disturbing, and it’s real,” he said. Hoffses said he’s aware of the university’s sexual assault counseling programs and services, but isn’t familiar with the details. “I don’t see them advertised much. I certainly don’t know about them, and I don’t think the average student knows either.”

When Perry took her job in the Wellness office at Hampshire College in August 2013, addressing sexual violence was an important, but limited, aspect of her job description. Since then, she said, her role has shifted dramatically. “My job now is 80 to 90 percent about sexual assault prevention and response,” she said. “It’s time to focus on this. It’s a once in a lifetime opportunity to educate while people are really paying attention.”

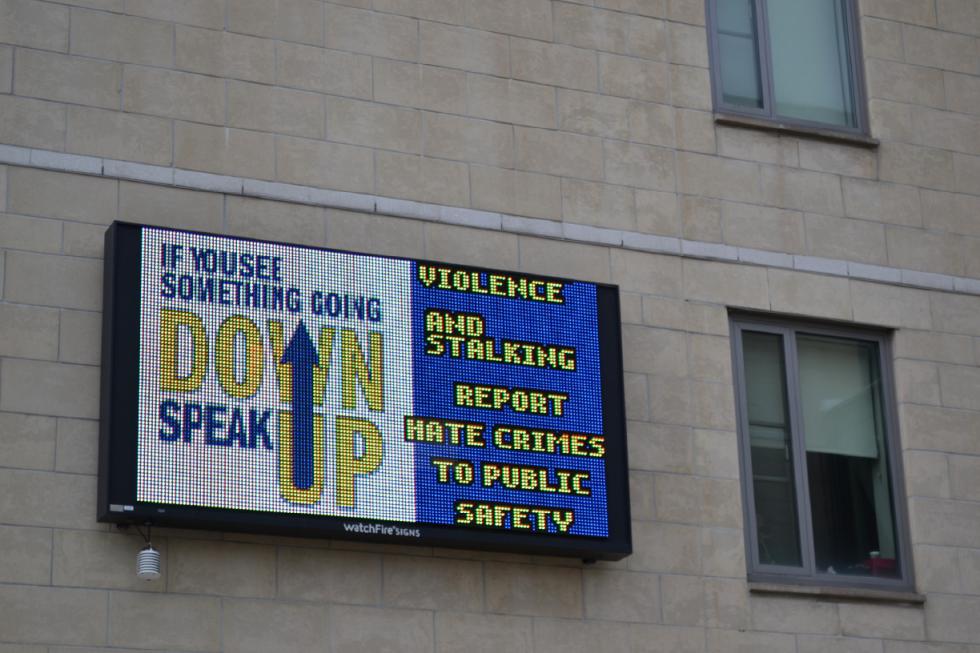

The small size of Hampshire empowers staff to revise and add policies continuously, Perry said. Most of her attention right now is on the bystander training program, a new initiative this year designed to increase students’ willingness to speak up or intervene when they see potentially harmful or violent activity among their peers.

To get this program off the ground, Perry asked her work study students which of their friends on campus they look up to and trust. “We selected 800 names. Then we picked out the folks who were mentioned by three or more students, which left us with about 50 students,” Perry said. Out of that group, so far 29 have gone through an eight-hour training on intervention and support.

“We’re hoping it has a ripple effect on campus,” she said. “I can’t do an eight-hour training for every student, as much as I would like to. This is our way of using peer pressure for good.”

Arianna Rose, a graduating Hampshire senior, has been working closely with Perry over the past two years to help get the word out about sexual assault. “I don’t think there are enough students at Hampshire taking this seriously,” she said, adding that several times she has had to take down posters advocating for consent after they were defaced. “We really care about feminism and social justice on this campus,” she said, “but that also means we’re more likely to underestimate the problems that exist at Hampshire.”

Two years ago, Rose founded a support group for survivors of sexual assault — a community in which she counts herself. She did this, partly, out of a sense of frustration. “I felt a very strong lack of resources for survivors that went beyond people telling us, ‘We’ll do what we can to get you justice and hold the perpetrator responsible,’” she said. “Once you identify as a survivor, what do you do with that? We needed a new group. Not for therapy, but for community and solidarity.”

The survivor group is primarily for Hampshire students, although Rose said a handful of students from other area colleges have reached out and asked to join.

Should school administration have thought to create this group first? Rose doesn’t think so. “This is for us, by us. It doesn’t concern the administration. They aren’t students. They don’t know what the climate is like for students right now. I want this group to be as untouched by the school as possible.”

Instead, Rose hopes the school will create a full-time position for a counselor dedicated to working with people who have experienced sexual assault. “There are plenty of people you can go to at Hampshire, but in order for survivors to feel truly respected and listened to, they need someone who really has time and energy to sit down and listen,” she said. “That administrative position is crucial, and it’s needed.”

Some campuses are tackling this conversation with more urgency than others. The students we spoke with at Westfield State spoke with confidence about the level of safety on campus, and several observed that discussion of sexual assault is initiated more often by the administration than by the student body.

“I haven’t heard much discussion among students,” said Jennifer Torres, aside from posters and a few events each year. Torres, a senior, said that she has heard about a sexual assault on campus once or twice since she arrived.

She remembered a self-defense class for female students, which was put on by the school a few years ago in response to one case. “I haven’t heard of them doing the classes again,” she said, “but I certainly think they should.”

Responses among the students we spoke with on the Mt. Holyoke campus were similarly muted. Sarah Eisner, a freshman, said she thinks the issue gets talked about enough, and that she feels safe on campus. “I think the issue is talked about more here because it’s a women’s institution,” she said. “I really like the feeling of women banding together here to feel safe.”

Part of what makes Mt. Holyoke feel safe is its small size and quiet atmosphere, said Elena Albanese, a junior. “There are parties that go on in the dorms, but when it comes to social life, you have to go seek it out. A lot of students here go to UMass and other schools to party.”

Yael Silver, a freshman, agreed. “I feel safer here than when I’m at other schools around here,” she said. “I’ve been told that if you are going to go to a party at UMass or Amherst, take a buddy. People get assaulted at those schools more frequently than at others.”

Over at Amherst College, freshman Denzel Wood wasn’t sure he agreed with that assessment of his campus, but he isn’t surprised by it either. “Amherst College has had a past with sexual assault, and I think the administration is really acknowledging it now,” he said. “As a freshman, I feel like I’m coming onto a changed campus.”

Amherst has instituted several new programs in recent years to encourage dialogue about sexual safety, including a resource referral group for students called Peer Advocates of Sexual Respect as well as a school-wide day of relationship-themed games and activities called ConsentFEST, now in its second year.

Noel Grisanti, a sophomore and a Peer Advocate at Amherst, led the organizing of this year’s ConsentFEST, which was held in April and featured tables run by a mix of volunteers from sports teams, clubs, and student government. Some tables offered statistics about assault. Others were more interactive, like the table that prompted visitors to play charades with each other. During the game, students struggled to act out complex emotions silently — a good demonstration, Grisanti said, of how hard it is to communicate until you speak up about what you’re going through.

Peer Advocates try their best to be visible on campus, Grisanti said. They put posters in dorm rooms with the names of all 15 advocates, and they now frequently wear vests. “I’m wearing mine right now!” she said during our phone interview. “We really want people to know who we are and what we offer. We do workshops on healthy communication. We meet with students who need to talk privately. We’re trying to get everyone to talk about it more.”

Katie Reilly, a junior, joined the Peer Advocates a year ago. “Angie happened my freshman year,” Reilly said, referring to the former Amherst student who ran an article in the student paper in 2012 detailing her own assault. “That was a lot to take in. We were just getting used to living at college, and then this sort of bomb dropped on us.”

Reilly said she was encouraged to see the campus come together in the months that followed. “We still have a long way to go,” she said. “I am still telling friends a lot that they don’t know about how the prevention and reporting process works.”

It’s a communication challenge, she explained. “We can print posters until we’re out of ink, but we need to brainstorm ways to make this more salient to the student body.”

Bonnie Drake, a sophomore and Peer Advocate, agreed. “Nothing can change until the culture changes,” she said. “Before I got to college, nobody had ever had a conversation with me about consent and what it should look like. I’m glad it was such a large part of our orientation. I’ve had friends and family members be sexually assaulted, and it’s something people just don’t talk about.”

When asked about how the administration might help, Drake offered two suggestions.

First: students need more space on campus for socializing. “Pretty much all of our parties happen in suite-style social dorms,” she said. “They’re built with a common room in the middle and bedrooms branching off from there. Those are small rooms, and when you’re packed in there with the lights low, people just have to touch each other. That can be changed. We need to move parties into larger spaces.”

Second: too many students feel overworked. “I’m in finals right now, and I have 88 pages of writing due over the next week,” Drake said. “A lot of students feel that the only way they can take a break is to binge drink, because they have really small windows of time when they’re not working. That’s just not healthy. We need to look at quality of life, and how stress manifests itself.”

Through all of these interviews about sexual assault, a pattern is clear. Although the issue’s increased visibility is constructive, campus events and discussions have a finite impact on students’ private actions. Campus culture must also change from within.

Or, as Amherst College junior Jeremy Van put it, regarding his fellow students: “We’re good at talking about the issue, but I don’t think people are any more sensitive or cautious now when they’re out trying to get with a girl or otherwise. I feel like everyone just takes a third-person point of view on the whole situation unless something actually happens to them.”

Administrative programs are looking to support students. But do students feel safer on a day-to-day basis as a result?

Van doesn’t think so. And living on a small campus doesn’t help either, he said. “We’re 2,000 kids, and there’s one dining hall,” he said. “If you want to get away from someone, it’s not possible unless you sit in your room by yourself. The question should be — can you deal with the situation without having to change your personal schedule? I’d say no, not effectively. That is a huge issue.”

Van added that he does not blame the college. “There’s only so much they can be expected to do,” he said. “In the end, having close friends you can trust and that are there for you — those are real relationships. That’s more effective than any administration.”•

Contact Hunter Styles at hstyles@valleyadvocate.com.