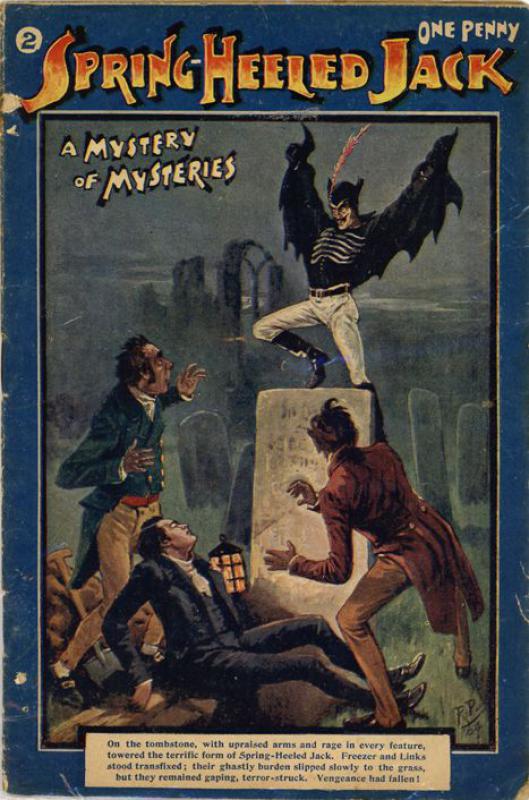

Spring-Heeled Jack, in addition to being the best-named apparition since the Mad Gasser of Mattoon, was a frequent haunter of Victorian London and, eventually, other parts of Great Britain. He was known and feared for his habits of sudden attack via tearing with metal claws and breathing blue fire, and the black-caped scoundrel often left the scene of a crime via inhuman leaps.

There’s an odd echo of Spring-Heeled Jack in the pantheon of Massachusetts anomalies. The Bay State has hosted a surprising number of monsters, ghosts, and entities. The catalogue starts early in the state’s history — mysterious visitors with unusual, futuristic technology and abilities supposedly visited colonial Gloucester. More recent times have seen such inexplicable occurrences as the so-called “Dover Demon” of Dover, Mass., a diminutive, big-headed creature spotted by more than one observer in 1977, and a miscellany of anomalies (even Bigfoot) around the “Bridgewater Triangle” in southeastern Mass. The list of hauntings here is, of course, substantial. But a particularly villainous Provincetown specter ought to give potential Cape Cod vacationers pause.

Chances are high he’d go unnoticed in contemporary P-town, overshadowed by folks like the omnipresent bicycler of recent years who’s dressed like, well, a pastel chess piece, maybe? But the Black Flash, says many an online source, spent a few years scaring the wits out of P-town folks, from 1938 through the end of World War II. He shared Spring-Heeled Jack’s penchant for a black cape. At least one observer reported the breathing of blue fire, and another claimed that the Black Flash got away courtesy of leaping a 10-foot hedge. It’s hard to avoid the question of whether Spring-Heeled Jack hopped aboard a transatlantic clipper.

Steve Desroches, writing in Provincetown Magazine in 2011, traced the Black Flash story to its origins. Desroches says it all began with kids who came home reporting terrifying encounters with “something big. Something that growled. Something all in black.” But then an adult P-town resident ran into the thing, and from her came reports of glowing blue eyes, incredible jumping ability, and, oddly, silver ears. As happens with many an anomalous encounter, it seems that everyone wanted in on the act, and reported sightings increased.

A great account of the Black Flash can be found in the 1997 Joseph Citro book Passing Strange, an excellent read about New England weirdness past and present. Citro based much of his version on the work of the now-deceased folklorist Robert Ellis Cahill, author of the 1984 volume New England’s Mad and Mysterious Men, who talked to P-town residents about the Black Flash. One of his interviewees reported that he was “black, all black, with eyes like balls of flame, and he was big, real big … maybe eight feet tall. He made a sound, a loud buzzing sound, like a June bug on a hot day, only louder … he disappeared like a flash.”

Troubling indeed. Stories like that led Desroches and others investigators like writers Theo Paijmans to dig deeper into the record. For better or worse, behind all the tales was, alas, a more prosaic truth. They found that the first written record of the Black Flash incidents comes from the Provincetown Advocate of October 26, 1939. There you’ll find a front-page story that acknowledges the ongoing tales, but chalks them up to cabin fever and, with a tone more Onion than New York Times, features a quote from a Capt. Phineus Blackstrap: “We’ve had the ‘Black Flash’ here every fourth year ever since I was a man and boy and he never harmed no one. Some usta say he was looking for his vessel that was lost oc [sic] the Race and others usta to say that he has a date to eat skully-joes with the Devil out at Peaked Hill when the first ones is ripe. I never seen him without he’s gnawing away at a skully-jo.”

Desroches claims to have gotten to the bottom of the business via a later newspaper quote from a former police chief who chalked the business up to four teenagers. One would get on another’s shoulders, he said, don a black cape and use a flour sifter for a mask, hence the account of silver ears.•