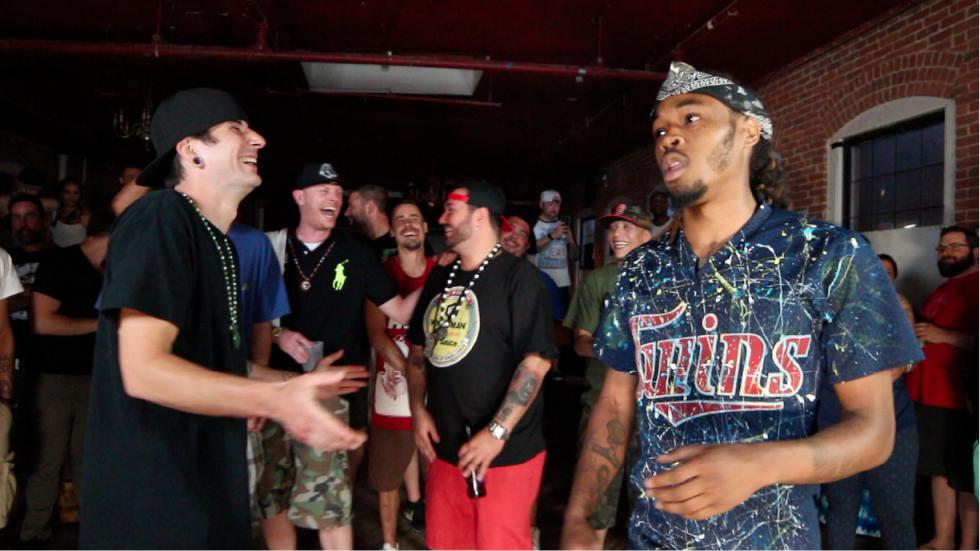

At the Waterfront Tavern in Holyoke, a rap battle between Hoodie Cruger, who is black, and Petey Mitch, who is white, turns racist.

“I got rap sheets to rival my rap sheets,” spits Petey. “For your life, somewhere someway, had to pay two cents a day. That’s not what I meant to say — I’m really not racist.” The crowd — about 60 people, almost all men — goes from hooting loudly to hissing and whispering. New to the rap battle scene, I scan the horizon for the nearest exit.

Hoodie smirks, priming for his turn.

“I’m from Springfield where niggas spring steel,” Hoodie starts. “The cops’ll show up like whoah, this is a raw scene. I put 16 holes in this cracka like he a saltine.”

Holyoke has one of the highest crime rates of the state’s small cities, but on this battleground words become violent, and it stops there.

“It’s all a big show. It’s like grown men writing poems for each other,” says Jason Weeks, co-owner of the 413 Battle League, the show’s organizers. “They have the goal of making the other person look smaller, but no one’s going to kill each other.”

Holyoke Police Sergeant David O’Connell says he isn’t aware of officers being deployed to one of the Battle League’s monthly shows at the Waterfront. “Never heard of them,” O’Connell says of the League. “That’s probably a good thing.” However, not all local shows are so peaceful. In April, for example, three people were shot in the lobby of the Hippodrome in Springfield following a concert.

Weeks, 33, and co-owner Tony Daniele, 35, started the 413 Battle League in 2012. The two Valley natives — joined by a mutual love for the art — started bringing people together for rap battles, found there was no shortage of interest, and so decided to formalize the scene into the 413 Battle League. The duo schedule and promote the shows as well as decide which opponents will face off in battle. Artists are paired based on how well their styles will match or clash. They do all of this on top of their day jobs — Weeks is a chef and Daniele a “therapeutic mentor for at-risk children in Springfield.” They’ll leave it at that, they say, for fear their involvement in the hip-hop scene will be perceived as a professional conflict. Sponsors, they say, help cover the event costs — the venue, videography, DJs, and occasional cash prizes for tournament winners. When asked about the dollar figures, Weeks declined to get specific.

“We’re not in this for the money,” Daniele says, laughing. “Definitely not,” Weeks agrees, shaking his head.

It’s Saturday, and tonight’s battles are just one phase of a months-long tournament, for which the eventual winner, chosen by a jury of local rappers, will receive a $413 cash prize. The battles take place in a large room at the rear of the space — some of its windows are boarded up and cobwebs hang from the ceiling, but the acoustics are good. Rappers go head-to-head in this evening’s seven battles. Each lasts about 15 minutes. In between battles, DJ Benny Black spins hip-hop and the crowd grabs drinks at the front of the tavern, bringing their beverages out to the patio to take in views of the Connecticut River.

Daniele and Weeks introduce me to Chris “Brash” Rapple, who they say they’ve rapped with for years. With a last name like Rapple, you’d think he’d leave his rap name at that, but Brash is a name he says he “got stuck with.” Rapple says the battles are all about taking your “lumps” and putting on a good show. He says creativity comes in their ability to devise interesting ways to insult an opponent.

“Every human being has faults,” Rapple says. “In what kind of weird ways can I insult this person?” When a line that the artist expected would draw crowd reaction falls flat, Rapple explains, that messes with momentum. Crowd control is important. “There’s no music to hide behind,” Weeks points out.

Daniele doesn’t rap, but is an avid listener. He stands less than a foot away from the battling artists. He has a visible tell when a rapper drops a “sick bar.” He bites his lip, squints his eyes, and nods his head in affirmation.

Tightly woven schemes in rebuttals earn points, Rapple explains. “It shows you can go off script.”

A lot of it’s psychological, says Rapple. “I’ve seen a lot of emcees get distracted because they start making eye contact with people.”

It’s easy to see how that could happen. Each rapper has his own way of handling an opponent spewing insults inches away from his face. Hoodie Cruger likes to stare them down.

On this night, a slight smile is visible at the corners of Hoodie’s mouth as Petey raps that Hoodie isn’t that gangster. Then Petey gets into a good rhythm: “I’ll beat you in the heat until your dreads loosen,” the crowd starts hooting and jeering, and Hoodie’s eyes come up from the floor to meet Petey’s in a steady gaze.

“They’re talkin’ about you and when the crowd’s reacting to what they’re saying, you’re either gonna get mad or accept it,” says Hoodie — Kavante Brantley, 21, of Springfield. “I enjoy it. I sometimes lock eyes to see if he’s as into the art as I am.”

Rapple says there’s an artistic bond that stems from the rivalry. And sure enough, in another battle, just after Colly C and Learic finish tearing each other apart, I see them palling around on the back patio. “If you’re not connecting deeply with the people you’re rapping with then you’re missing the point of hip-hop,” Rapple says.

Many of the artists tell me that things can “get heated” in the sense that two opponents sometimes truly don’t like each other. “Beef happens,” says Weeks. “It’s settled over the battle. We’re not solving every gang war, but it’s an outlet.”

To that point, Brantley says “I’m never angry. It’s like going to the court and shooting hoops — I just wanna win.”

I find Presha “running lines” in the back room in preparation for his battle. Like a prize fighter shadow boxing, his hands jab out in front of him as he spits lines.

“The competition keeps me coming back,” says David “Presha” Colon, a Holyoke native. “I want someone who’s gonna challenge me.”

Presha’s lines are rich with metaphor, simile, word play — and guns. “I’m a product of my environment,” Colon says.

“Break the habit — you catch a sacred marriage — let it ring out the box like it came from Jared.” He describes this line as a “gun bar” because the line’s “let it ring” does double symbolic duty.

Colon says once the match-ups are announced, he starts preparing. The artists have about a month before each battle to extensively research their opponents.

“You find out everything you can about your opponent and bring it to him,” Colon says.

For many of the artists, who refer to stints in jail and life on the streets, rap battles are a way to vent, to say things they can’t normally say.

“I can shoot and I can kill him — that’s easy,” says Colon. “This is how we channel our aggression. There’s a mutual respect. You air out what you have to air out instead of going to shoot people. You can kill ’em 15 times in one verse. That’s battle rap.”•

Contact Amanda Drane at adrane@valleyadvocate.com.