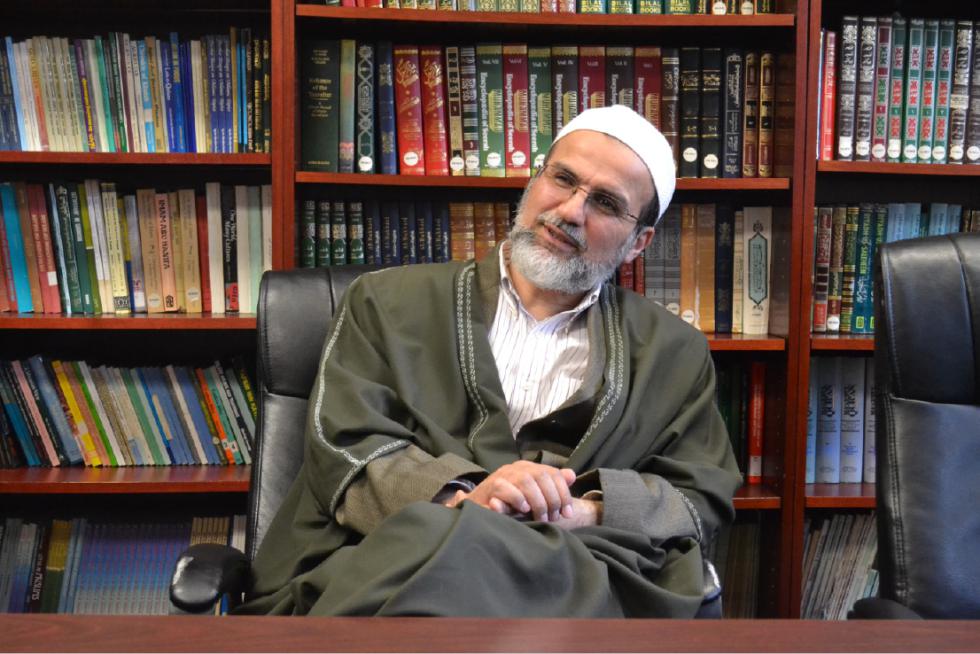

Wissam Abdul-Baki leans forward in his chair.

“Try it,” he murmurs. “Say ‘Allah.’ ”

I do as he instructs, drawing out the second ‘A’ into a long “aww” sound. I think it sounds pretty good, but he pats his chest. “Start from here. Let it come from the bottom of your heart.”

I drop my voice an octave and try again. The low vowel resonates in my chest. “Yes,” he says. He leans back from the conference table, satisfied. “If someone has stress, let them repeat this name,” he says. “Let them say it deeply, 10 times, with deep breaths: ‘Alla-a-ah.’ ” The imam rocks his knees, and his padded swivel chair swings from side to side.

Behind him, shelves and shelves of poetry, literature, and religious texts fill the wall. “If you ask a Christian in Arabic who is his god, he will say Allah,” he says. “If you ask a Jew in Arabic, he will say Allah. This is a word that joins us.”

I’m sitting with the only imam this side of Boston. We’re in a quiet office at the Islamic Society of Western Massachusetts, a mosque and learning center on Amostown Road in West Springfield. The center opened as a nonprofit community organization in 1982, and it serves as a religious and social space for local Muslims.

Abdul-Baki has a paid full-time position here. As the center’s spiritual leader, he leads five prayer sessions each day in the mosque, or “masjid,” to use the Arabic pronunciation. He spends the in-between hours in conversation with anyone who seeks counsel. Right now, this includes discussions of the practice of worship and fasting during Ramadan, the month-long religious holiday that continues through July 17.

He says he did not choose to be an imam — it was fated to turn out this way. But his background shows an extensive interest and devotion to Islam. After his studies in Islamic law at the University of Medina in Saudi Arabia, Abdul-Baki served as imam at mosques in Lebanon, Peru, Bolivia, and Venezuela before returning home to the United States.

As with many rabbis, ministers, and other clergymen, Abdul-Baki leaves his door open to visits from the general public. Around here, that audience is small. But it’s growing. In the United States, where 78 percent of the population is Christian, Muslims comprise less than 1 percent of the American faithful. But globally, one in four people identifies as Muslim, and a report released in April by the Pew Research Center found that Islam is growing more quickly than any other religion in the world. By 2070, the report predicts, the number of Muslims worldwide will surpass the number of Christians.

This mosque is the largest in the area, Abdul-Baki says. He sees enough Muslims visiting the center — plus occasional non-Muslim visitors — to stay busy.

There used to be an imam in Worcester, he says, but now you have to go to Boston to find another imam in Massachusetts.

“Islam has never gone away, and now it is in a rebirth,” he says, referring to the rising number of worshipers worldwide. But this rebirth has brought us a lot of pain and headache.”

Abdul-Baki is referring to the many times in recent decades that extremist factions have hijacked the image of Islam for military and political purposes. “Those people do not represent Muslims,” he says. “My religion stands for the freedom of people to choose. God created you free, and people need to be free. Liberty, equality, freedom, justice — these are essential parts of my faith. Not violence.”

The prophet Muhammed did not force Islamic law onto people, he adds. “He brought them God-consciousness. If you don’t have that, you cannot choose your religion. The word of God has to come with acceptance. If you force people into Islam, it’s not Islam.”

When I arrive on a Wednesday afternoon, he is standing with his shoes off in the corridor outside the masjid, smiling and talking quietly with a young man and his two children who have just arrived to pray. He says he is often engaged in these short, casual hallway talks. Otherwise, he is at his desk dealing with emails, or stopping in at the Iqra Academy — an Islamic school program for teens.

The visiting father goes to the restroom to wash up before prayer, and Abdul-Baki takes me on a tour. The masjid is mostly dark carpet and white walls: bright, open, and sparsely decorated. On the way in, he gestures to several large calligraphic paintings. The interlocking Arabic script is beautifully designed. “Here it says that God created all human beings — male and female — as equals,” he says. “And here is an invitation to enter into peace, and to not follow in the steps of the devil.” Inside, he opens both arms and turns slowly to indicate the space. It is calm and quiet in here. Dhuhr, the second of the five daily prayers, was held here a little before 1 p.m., and Asr, the third prayer, isn’t until just before 5 p.m.

“It is simple in here,” he says. “Color inside does not matter. The idea is to have a roof and a clean space where you can pray. The rest is just details.”

Often, several hundred people attend Friday service. The rest of the week is much quieter. Sunni and Shiite Muslims pray together here. Recently, he says, the masjid has begun to attract more immigrants and refugees from Africa and the Middle East.

During his sermons on Friday afternoons, Abdul-Baki reads passages from the Quran in Arabic, but the service — which applies those religious lessons to issues and news in the local community — is conducted in English.

Although he doesn’t get to roll out his Spanish very often, Abdul-Baki is fluent in that language as well, having served as imam of the largest mosque in South America — in Caracas, Venezuela — before moving here to reconnect with his family, who have lived in the States for four generations.

Since many administrative tasks are handled by the center’s president and board of directors, the imam’s job is mainly to provide education, counseling, and healing to visitors and the larger community. Abdul-Baki represents the center at interfaith events, and he’s a volunteer chaplain at the Baystate and Mercy medical centers in Springfield.

Abdul-Baki lives next door to the center with his wife and five children. When he is not here, he says, he is with them, often traveling together and spending time with local relatives.

I ask him about the rhythm of his work day. This question is easy to answer, he says, because daily prayer provides him with an unchanging structure. “You have to pray in a particular way, and at particular times, and this brings discipline into your life,” he says. “Islam by nature teaches you how to organize yourself.”

In the morning he tends to read: literature, poetry, but also scholarly articles and interpretations of Islamic law. “This school of thought is very flexible and wide, with different viewpoints,” he says of Islamic studies. “However much you read, you need to read more. I am a specialist in this field, but I’m always a student.”

Most of Abdul-Baki’s visitors come from Western Mass and northern Connecticut. But that may change in coming years. As the center grows, more visitors arrive for prayer and counseling. And Abdul-Baki feels more responsibility to his community each year. “It is more work,” he says, using the Spanish word: trabajo. “But the all-merciful God Allah, he helps. And I have good people all around me to lend a hand.”

This sense of gratitude is profound, he says, and it arrives in full force when he wakes in the morning. “That is the most important time for me,” he says. “When I get dressed and put my head down before the all-merciful God. I need it. For me, it is the most beautiful time.”•

Contact Hunter Styles at hstyles@valleyadvocate.com