A pair of two-character plays now on area stages illustrate the crucial importance of casting. With only two actors – both of them, in these cases, onstage the whole time – the stakes increase. The players not only have to complement each other, artistically and dynamically, they have that much more responsibility to fully embody the play. In one of the current productions, a cheeky piece of type casting turns up trumps; in the other, a shocking example of miscasting skews a promising production.

Debra Jo Rupp’s middle name, if she didn’t already have one, could be Kooky. She’s known to a national audience as the mood-swing mama with the buzz-saw laugh on That ’70s Show, and around here from numerous regional theater appearances, most memorably her solo turn as the irrepressible sexologist Dr. Ruth. Rupp’s diminutive frame, nasal speech, bustling energy and comic flair make her a natural as slightly eccentric, wisecracking women.

Which is exactly what she’s currently playing at Chester Theatre Company, and triumphantly transcending the type. Her character in Memory House, and the play itself, are often very funny, but Rupp also makes the serious, even painful, core moments grow organically out of her offbeat character.

Maggie is the divorced mother of 17-year-old Katia, a quirky New Yorker who uses sarcasm and self-deprecating humor to deflect feelings of failure, both professional and parental. It’s New Year’s Eve and she’s at home (“I used to have a life”) peering into The Joy of Cooking in her first-ever attempt to bake a pie – a running gag that provides the drama with regular jolts of hilarity.

Katia, meanwhile, is avoiding a college application essay that’s due before midnight. the assignment, to travel through her “memory house” of childhood experiences, has brought up all her questions and insecurities about having been adopted from Russia. She’s not procrastinating so much as acting out her anger, resentment and confusion – as well as treating her mother to her full repertoire of adolescent button-pushing skills.

Caitlyn Griffin is the other half of this two-hander. She’s a college student making her professional debut, but she more than holds her own with her experienced colleague. Her role is rather underwritten, leaning too heavily on Katia’s moody truculence, which made me just as exasperated with her as Maggie is for much of the play. But Griffin clings as tenaciously as her character to her through-line with impressive presence and poise.

Kathleen Tolan’s play tracks the ebb and flow of this mother-daughter brawl, and Sheila Siragusa’s sensitive direction gives it shape and tension. But it’s far more than that. Much of the sometimes scalding give-and-take revolves around the politics and ethics of cross-cultural adoption from poverty-stricken nations and families.

Katia says she’s unable to construct a “memory house” because she has no early memories, at least none that have anything to do with her American self. She concedes that her adoptive parents saved her from the seedy Russian orphanage where she was housed (“I owe you my life. I hate that,” she spits). But the sense of having been ripped from her “bleeding country” into “the country of bullies” rankles and cannot be resolved – certainly not for a glib application essay.

The issue isn’t resolved in the play, either, though there is a resolution that beats the midnight postmark deadline, with a satisfyingly unexpected payoff. But the question of cultural and economic looting of the impoverished world hangs over this sizzling battle of love and need, and will follow you home.

No big global issues are explored in Frankie and Johnny in the Clair de Lune, now playing at the Berkshire Theatre Group – unless, of course, you count the universal longing to love and be loved, to make a human connection in this cold, harsh world.

Terrence McNally’s play begins with the kind of human connection that involves panting and moaning and ends in shouts of delirious pleasure. We hear all this in the dark (sorry, voyeurs) and when the lights come up we find the title characters in contented afterglow. While she’s idly wishing she hadn’t quit smoking, he’s feeling that “something is going on in this room – something important.”

Despite the coincidence of their names with the famous song, Frankie and Johnny are not lovers, just acquaintances from work – she a waitress, he a short-order cook. For her, this has been merely a “That was nice, let’s do it again sometime” kind of evening. So she’s startled and a little freaked when he suddenly, passionately, proposes.

As in Memory House, one of the characters here is quirky and surprising while the other one mostly does the expected. Johnny is both a longtime loser and a die-hard dreamer. Stuck in a dead-end job, he’s trying to improve himself by reading Shakespeare and by willing himself, awkwardly and recklessly, out of a diffident shell. “I’m not good with people,” he confesses at one point.

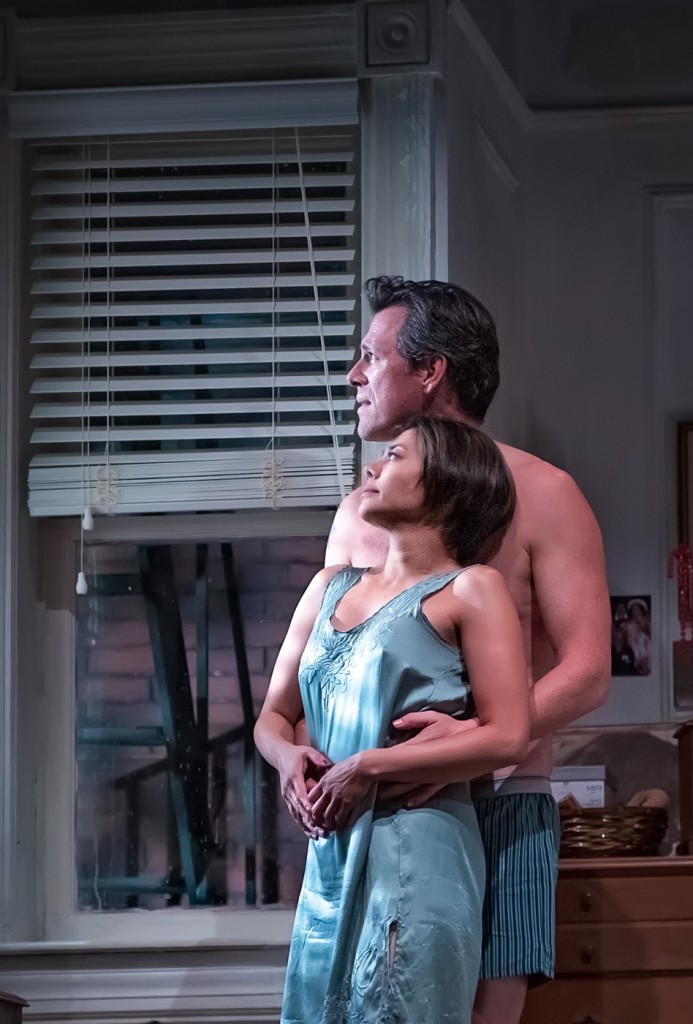

Angel Desai and Darren Pettie in “Frankie and Johnny in the Clair de Lune.” Photo by Michelle McGrady.

So it’s hard to fathom why Darren Pettie’s Johnny is so smooth and cocky, even smarmy. The words he says bespeak a dogged openness and a clumsy charm, but his expression, tone of voice and body language are cool and comfortable. I didn’t see a burning heart fighting through loneliness – I saw a player. Given that, it’s not hard to understand why Angel Desai gives so much energy to Frankie’s puzzlement and distrust, and relatively little to the woman’s growing attraction to this gauche Romeo.

McNally’s 1982 play is a rare heterosexual love story from a much-lauded chronicler of gay celebration and sadness. I didn’t know this play before opening night, and what I got from the dialogue was that the play is supposed to be a hesitant coming together of two lonely souls, one emotionally naked and boyishly romantic, the other literally naked for much of the early going but wary of moonlight romance. (Thus the title: A full moon shines into the one-room apartment, and Debussy is on the late-night radio.)

It’s hard to know if the director, Karen Allen, wanted to put a whole different spin on the character dynamics, or was simply given an actor with a one-note range. Pettie’s performance tilts the play’s tone and thrust until I, at least, was more suspicious of the guy than Frankie is. Indeed, when she repeatedly asks him to leave and he doesn’t, it’s hard to see why she doesn’t call the cops.

This dynamic also impedes Frankie’s own journey out of her own defensiveness, though I totally bought Desai’s Frankie – down-to-earth, street-smart, wearing her own shell toughened by disillusion and New York. That said, I think she’s too attractive for the role – they both are, really. The script implies they are ordinary-looking folks, hovering around 40 and worrying that time is running out. But Desai is a real beauty and Pettie has the cut good looks of a soap star.

Despite the differences of topic and feel, Memory House and Frankie and Johnny share some traits. Both track a pivotal encounter in real time. Both involve women carrying disappointments into middle age – Frankie and Maggie are artists, an actor and a dancer, who’ve put their dreams aside. And both plays look hard but sympathetically at the guts it takes to face down your fears, whether they arise from a half-forgotten past or an unknowable future.

If you’d like to be notified of future posts, email StageStruck@crocker.com