When the railroad tracks that run through the Valley were improved for heavy freight trains and passenger rail service, people were excited about the potential of ditching their cars and using the train to get up and down the Valley, taking it to work or to a show and back.

But that’s not happening now. Instead of getting all aboard with a cup of coffee and bagel in the morning before work, people are using the new service to take weekend-long trips to points south, like New York City, Washington, D.C., and Philadelphia.

Valley residents eagerly await commuter service, but it’s going to take a lot longer to head down that track than local officials and planners had hoped. In the meantime, people are still pretty happy to be able to get on the train in Northampton and Holyoke.

“It’s kind of exciting that it happened just as I was going to college,” said Quinn Doherty, 19, of Northampton. Doherty attends Ursinus College just outside Philadelphia. At the Northampton station, waiting for the train to take him on a five-hour ride back to school following the long Columbus day weekend, Doherty said he planned to write a paper along the way. His father, Michael Doherty, 49, said the ride isn’t cheap — $207 round trip — but it makes it much easier to get Quinn back and forth. Michael says he would use the train, too, if he can take it to Montreal.

“Me too,” said Quinn with a grin.

“Because the drinking age is 18,” his father needled.

“Yeah,” Quinn Doherty said with a chuckle. He looked down at his phone. “The train’s late today.”

Increasing connectivity along the Knowledge Corridor, the stretch between New York City and Northern Vermont serviced by Amtrak’s Vermonter line, is a goal that’s been in play for years. Commuter rail service remains a major piece of the planning puzzle.

For 15 years the tracks that run from Springfield, to Holyoke, Northampton, and Greenfield lay dormant. After the tracks fell into disrepair during the 1980s, stakeholders saw a dive in ridership and rerouted the train into Amherst and Palmer instead of repairing them. Between climate change and unstable gas prices, interest in trains returned in recent years and so the U.S. Department of Transportation launched the Knowledge Corridor project, which brought $73 million in construction aid to the railways along the Connecticut River. Former Gov. Deval Patrick was a proponent of the project and helped direct state funds to the cause, including commuter rail.

Commuter service was originally scheduled to arrive in the Pioneer Valley by 2016, but Pioneer Valley Planning Commission’s executive director Tim Brennan said that bringing commuter service to the Valley could take as many as six more years.

Still, ridership along the improved line has been on the rise. Boarding at Valley stops new and old has increased by 70-90 percent over last year, Brennan said. And according to Craig Schulz, a spokesperson for Amtrak, the company has seen a 3.4 percent increase in the overall Vermonter ridership over the past fiscal year.

The change-over

Brennan said the delay is largely due to a new administration — Gov. Charlie Baker took office in January.

“Now this has turned into advocacy because we have a new governor and a new administration, so in a sense we have to start over again,” Brennan said. “There are new men and women who have to be convinced of the merits of what we’re looking for.”

To increase transportation up and down the Valley, ease traffic congestion, and provide a more environmentally friendly transportation alternative, Brennan is working with state and local officials to bring two morning trains (in both directions) through Valley stations and two in the afternoon, including one that would coincide with rush hour traffic.

In a new report the Pioneer Valley Planning Commission released in August, researchers outline three viable options for bringing commuter rail service to the Valley. Two of the options begin with obtaining retired equipment from MBTA lines — three locomotives and two to three coaches per locomotive — sending them away for analysis, and rehabilitating them accordingly for use in the Valley. From there, Brennan said, ownership of the commuter trains could either be put in the hands of a local commission, just as a local board governs the Pioneer Valley Transit Authority, or be ceded to Amtrak.

Step one for both of those options requires the MBTA to retire and release the locomotives, Brennan said. The MBTA is slated to release the trains next month once new equipment is up and running. If professional analysis shows that recycling the trains is feasible and cost-effective, the $30 million the Department of Transportation has earmarked for the Knowledge Corridor will be used for the locomotives’ rehabilitation.

A third option, which Brennan said is unlikely as it is more money than the project has earmarked, would send existing shuttles already running between New Haven and Springfield up and down the Valley to offer commuter service. Right now, Brennan said, several shuttles sit in Springfield upon arrival. They could easily provide the service, he said. But high rates would be tacked onto the north and south runs because of congressional mandates that Amtrak charge flat rates for their services, Brennan said.

Let’s get things in motion

With $120 million already invested locally on platforms and additional infrastructure, Brennan said he’s urging leaders in Greenfield, Holyoke, and Northampton to write to the Baker administration, to “reinforce the interest about adding service to the existing corridor, now that the capital improvements are essentially done.”

“We want a return on that investment,” Brennan said.

Northampton Mayor David Narkewicz said he’s drafted a letter — addressed to Baker’s administration — that is currently circulating between his office, Holyoke Mayor Alex Morse’s office, and that of Greenfield Mayor William Martin.

“Obviously a lot of people work up and down the Valley so there’s all kinds of potential we see in terms of economic development,” Narkewicz said.

In the Valley, rail service is here, but it isn’t necessarily easy to hop on the train.

For one, all tickets need to be bought in advance either by calling Amtrak or using online purchase options — none of the Valley stations has kiosks to purchase tickets. And the stretch between Springfield and New Haven is under construction, causing cancellations in the shuttle service as well as delays and disruptions along the Vermonter line.

Before heading over to the Northampton platform, I tried to buy a ticket on Amtrak’s website, but a series of error pages told me the website was experiencing technical difficulties and instead offered a phone number to call. I decided to take my chances and went to the Northampton platform.

Waiting there with a couple dozen other people, I heard some joke that Northampton already needs a bigger platform.

Jim Sullivan, 66, of Northampton, said he’s taken the train to New York City four times to visit a friend since service returned last year. “It makes a big difference being able to walk to the station,” said Sullivan, adding that he also loves the social aspect of the ride and the knowledge that he’s doing something good for the environment. “It makes life a lot easier for students and older people, like myself.”

Hopping on the southbound Vermonter alongside Quinn Doherty, I was grinning at the prospect of something like the T coming to the Valley.

Assistant conductor Justin Winiarc, who is young, friendly and helpful — thankfully, given my lack of ticket — ushered us inside. The chug, chug, chug of the train set us in full motion and Winiarc began going seat to seat checking passengers who had tickets on their smartphones.

“Next stop: Holyoke, 12 minutes,” crackled an overhead voice.

We jostled and squeaked down along the Connecticut River. The windows on either side were a whir of fall colors.

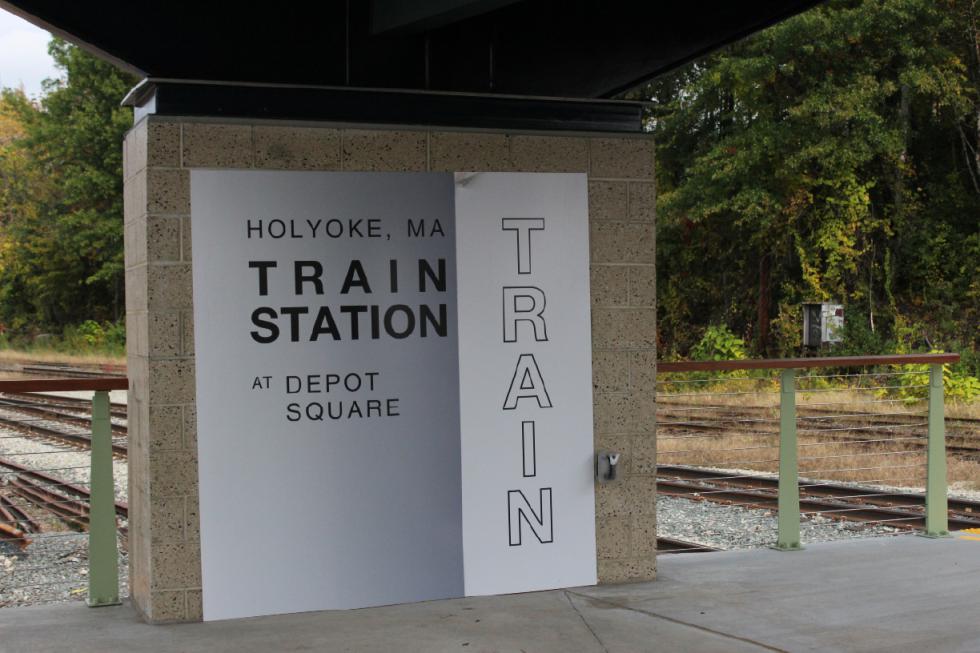

I step onto the platform at Holyoke’s train station at Depot Square and am greeted by a view of Holyoke that looks like it belongs on a Hallmark card — beautiful mill buildings, changing leaves, and City Hall all in one snap-worthy frame.

Commuter rail service may be a while, but it’s certainly exciting to be riding a train at all.•

Contact Amanda Drane at adrane@valleyadvocate.com

Because a lot of work has already been put into capital improvements, local officials are eager to see a return on the investment. Here’s a breakdown on the progress.

SPRINGFIELD: Large-scale renovations to Springfield’s Union Station — built in 1926 and unused in large part since 1973 — have been a long time in coming, but construction kicked into high gear over the spring and summer. The project, which rebrands the site as the Union Station Regional Intermodal Transportation Center, is helmed by the Springfield Redevelopment Authority. It will cost over $80 million in federal, state, and local funds.

Workers will overhaul the pedestrian tunnel connecting the terminal to the train platforms, restore the original terminal building and concourse, and replace the station’s canopy roof. The project also calls for construction of a 377-space parking garage and a 26-bay bus terminal.

The project is planned to be completed in fall 2016.

NORTHAMPTON: Northampton saw the return of passenger train service on Dec. 29, 2014, at a new platform built a couple hundred feet south of Union Station. That historic building, which opened in 1897, serviced train riders until 1966. It has since been converted to a nightlife hub, most recently with the opening of Union Station Banquets and the Platform Sports bar last year.

AMHERST: Service to the 161-year-old Amherst station ended last December as trains running the Vermonter line rerouted from Northampton directly to Greenfield. The little brick building — half of which is run as Amherst Pilates — was a no-frills waypoint, but it was not without its ridership: a fact sheet published by Amtrak shows 13,357 passengers getting on or off the train in Amherst in 2013, many of them university and college students, faculty, and researchers.

The future of the building is unclear, as Amtrak no longer leases the space from the owner of the Pilates studio.

GREENFIELD: The John W. Olver Transit Center in Greenfield opened in 2012. Construction of the center, which provides regional and local bus service in addition to Vermonter rides, cost $12.8 million. The facility relies in large part on solar and geothermal energy, making is the first zero-net energy transit center in the country.

HOLYOKE: Passenger train service returned to Holyoke on Aug. 27, via a newly-built $4.3 million station platform at Depot Square along Main and Dwight streets. Construction had begun in December 2014.

This is the first time Holyoke has had passenger rail service since 1967. Back then, trains stopped at the historic H.H. Richardson train station at Bowers and Lyman streets, built in 1883. But officials have stated that reopening the Richardson station was not feasible, since the track at that site features curves that modern trains are not able to safely navigate.

Instead, said Holyoke’s Director of Planning and Economic Development Marcos Marrera, the new platform is located at a separate historic spot — right where the original rail depot was first built, where both passengers and freight would arrive at the city.

“The platform is providing a valuable gateway to connect residents and visitors beyond this region, particularly south to New York City. It’s also provided significant lighting and increased sense of safety in the area,” said Marrera. “It’s already serving as an attraction to new investment, where developers see it as the first step in transit oriented development. Beyond that, our goal is to get increased passenger rail service throughout the corridor that lands us several trains a day, at an affordable price point.”