Sarah Sousa

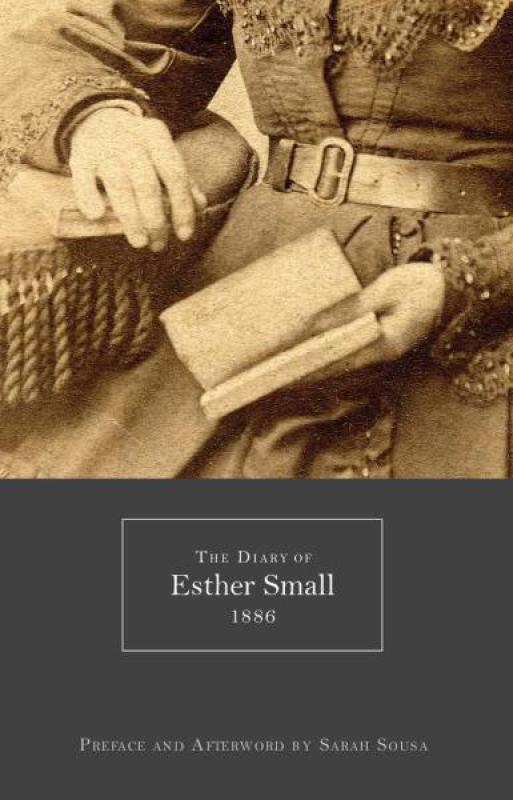

The Diary of Esther Small

(Small Batch Books)

The poem “Independence Day, 1886” is about the life of a woman Sarah Sousa first met in a faded 1886 pocket diary in an antiques store.

Sousa — an award-winning poet and writing teacher, who has received acclaim for her two books of poetry, Church of Needles and Split the Crow — was living in Phillips, Maine, when she found the red leather diary, with the name “Esther” pencilled in the front. The tiny pages were filled with handwriting in faded pencil and browning ink. She had the diary for about a year before she transcribed and edited The Diary of Esther Small while completing her master’s degree.

“Both the Diary and Church of Needles came out within one month of each other,” said Sousa, who moved from Maine to Ashfield six years ago with her husband, Grammy Award-winning musician Ray LaMontagne, and their two sons.

She saw Diary as a companion book to Church of Needles, Sousa’s book of poems, which couples diarist Esther Small’s details of 19th century marriage with contemporary themes and voices.

“I really did it because I wanted what I discovered in my research about the diarist to be available,” said Sousa. “She had tenacity and strength. I wanted to give her the voice she didn’t have through writing in her diary.”

Sousa found the pocket-sized diary in an antiques store in Maine. “I put it

away for awhile, because it was too small to read. She was saying her husband was beating her.”

As it turned out, Sousa discovered Esther had lived just two towns over from where she was living. “I did an online search of cemeteries in the county when I found her. It happened very gradually.” One of Esther’s diary entries lamented: “Why have I ever come to this small family,” which was an important clue. “The family name was ‘Small,’” Sousa explained. “She moved from New York, where her family was, before she married. She was saying ‘Why did I ever come to this Small family.’”

Sousa said the diary was a straight transcription. “They almost looked like little poems,” she says of the entries. “She wrote about the weather, about churning the butter. She cried because she was so homesick. I like to see the details of [women’s] lives,” Sousa said. “In her diary, she’s pregnant with what turned out to be her last child, at age 42. [But] she never says she’s pregnant in the diary. I looked it up in the census records; then I could see the clues. She talked about getting someone ‘to help her’ because she’s ‘not very well.’” Sousa said. Esther wrote that her husband, William, kicked her while pregnant, because her father-in-law said something about her that enraged him. She later learned that William was a Civil War veteran who served three to four years in the Union Army. William had called Esther “a New York whore,” according to Sousa. “He accused her of flirting with every man in town and kicked her,” she said.

“Some of the poems are very connected to what [Esther] was writing about. She has an almost apostolic voice in the diary, because she’s almost speaking to you, to the reader.” Sousa calls the poems inspired by Esther Small “persona poems.” “They’re like monologues in another voice,” she said. But to do the poems, “You have to find something in the character that resonates with you. Then you write from your own humanity. You open to your own experience and you draw on a well of feeling inside.”•