On a recent trip to the Bay Area to visit family and friends, I also (of course) saw three shows – a smart new comedy, a hit Broadway musical, and a big-tent extravaganza in which circus meets horse whisperer.

When this area’s summer-season lineups are announced in the spring, I’ll bet money that Stage Kiss, the latest from Sarah Ruhl to hit the regions, will be among them. Part of my certainty is the audience appeal of the playwright – author of Dead Man’s Cell Phone, The Clean House, In the Next Room (or The Vibrator Play) and other repertory favorites – and part of it is the play’s appealing premise and package: a backstage farce wrapped in a burlesque of dramatic styles within a cheeky satire of the theatrical life.

It opens in predictable but promising romantic-comedy territory: When two fortyish former lovers who parted bitterly are cast opposite each other in a sappy 1930s revival, their stage kisses quickly turn real and they fall back in love. But Ruhl’s play soon shoots off like a Roman candle in a shower of Ruhlsian gags and twists and not one but two plays within the play: art imitates life imitates art.

The suddenly reunited pair are called simply She and He – She married to a stolid, staid banker, He living with a chirpy schoolteacher half his age. Their director is a self-regarding nincompoop who follows up their stage reunion with another preposterous vehicle – a pseudo-gritty melodrama about a prostitute and an IRA gunman. The greasepaint hits the fan when Her husband and their alienated daughter show up, along with His ditzy girlfriend.

Stage Kiss, then, is a comic pastiche that takes affectionate, scattershot aim at showmance, self-indulgent theater folk, bad playwriting, overacting and other theatrical sitting ducks, including stage combat protocols, not to mention marital ties strained by sexual fantasy. Most of the seven-member cast play more than one role, often as parallel characters. The heroine’s husband in the first play-within-the-play is also Her real-life husband, and Her real-life daughter is also the play-heroine’s daughter.

Through a mixup about the curtain time, I arrived late for the performance at the San Francisco Playhouse, the city’s self-styled “off-Broadway company,” so it was hard to judge the production as a whole. The play demands a tricky stylistic balance between overlapping realities, both the on/offstage shifts and Ruhl’s trademark flights of fantasy (at one point everyone suddenly bursts into song). To this latecomer’s eye, that equilibrium didn’t quite settle. Some of the performers – most of them familiar Bay Area faces – overplayed both their “onstage” and “offstage” roles, just in different styles, while others navigated the shifting currents more adroitly.

It will be fascinating to see how the play’s cascading layers of fantasy and fun are handled in next summer’s production(s?) in this area – and I’m taking bets there will be.

I saw A Gentleman’s Guide to Love and Murder in its premiere at Hartford Stage, before it went on to Broadway and last season’s Best Musical Tony award, and loved it for its fresh take on the musical form, its affably cynical plot and its hilarious appeal to the peculiar human fascination with violent death. Now it’s on a national tour that stopped in San Francisco’s grand old Golden Gate Theatre for most of December, and I was glad to see it again.

The show is based on an Edwardian-era novel and the classic film it inspired, Kind Hearts and Coronets, in which a shabby young Englishman suddenly discovers he’s eighth in line to inherit an earldom and a fortune, and proceeds to slaughter his way to the front of the queue. The touring production is an exact replica of the East Coast versions, directed by Hartford Stage’s Darko Tresnjak and bringing along Alexander Dodge’s ingenious set, which recalls the gaslit music-hall era with a gaudy proscenium stage nestled into the larger setting.

In the original production and again on Broadway, Jefferson Mays played all eight of the ambitious young man’s ill-fated cousins, including a tweedy country squire, a toothy vicar, a matronly do-gooder, a stuffy banker, a hairy-chested body-builder and a melodramatic diva. Here the octet of blue-blooded victims was performed with Mays’ quick-change virtuosity, but without his playful panache, by John Rapson, who relied too heavily on broad burlesque and shameless mugging.

The cast, largely young – typical of road companies, composed of actors willing to leave the Big Apple for extended sojourns in the provinces – clearly enjoyed the opportunity of playing in this venerable old house to a sold-out audience of 2,000. Several company members have Bay Area ties, highlighted in the program in first-person vignettes that sought to give this big-business tour a cozy community-theater feel.

I don’t like animal acts. Most of them seem designed to show how smart the trainers are in making their charges do things that are unnatural to them; and in many cases, the animals’ cooperation is produced through pain and fear and hunger.

Circuses, of course, are the worst offenders, whipping and bull-hooking their captive “wild” beasts into submission, followed closely by the likes of Sea World, where naturally far-ranging, intensely social whales and dolphins are confined in pools the relative size of a hamster cage. It’s gratifying to report that the public has taken note: Sea World is in financial straits, and Ringling Bros. circus has just announced that it will take its elephants off the road this spring.

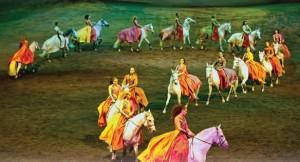

So I approached Odysseo with some misgivings. Billed as “a magical encounter between human and horse,” it’s a kind of rodeo-meets-Cirque de Soleil (though for that matter, rodeos are pretty brutal too), a massive spectacle with soaring music and bigger-than-IMAX projections, performed on a half-acre ellipse of sand under the world’s biggest Big Top by a cast of 60 riders, acrobats and musicians and 40 horses.

Cavalia, the show’s creators, make a big point of their humane practices, “designed to ensure the horses enjoy training with us and performing on stage.” No whips, spurs or hard bits are used, and commands are defined as “requests” which are “adapted and respectful of what they [the horses] are ready to offer.” And in fact, in the show I saw on the San Francisco waterfront, it was pretty clear that the horses were not tightly regimented, despite some remarkable synchronized movement. There were spontaneous moments of equine independence and individuality, which the crowd enjoyed as much as the more precise choreography.

Cavalia, the show’s creators, make a big point of their humane practices, “designed to ensure the horses enjoy training with us and performing on stage.” No whips, spurs or hard bits are used, and commands are defined as “requests” which are “adapted and respectful of what they [the horses] are ready to offer.” And in fact, in the show I saw on the San Francisco waterfront, it was pretty clear that the horses were not tightly regimented, despite some remarkable synchronized movement. There were spontaneous moments of equine independence and individuality, which the crowd enjoyed as much as the more precise choreography.

Indeed, with a couple of exceptions, the show seems aimed at demonstrating freedom rather than obedience, and partnership instead of mastery. Some of the most thrilling moments, for me, came from simply seeing bareback riderless horses suddenly galloping onto the stage, or clustering around a lone woman who followed their movements as closely as they did hers. (Women were at least half the trainer/riders, not merely circus-style mounted mannequins, though there was a bit of that too.)

There were acrobats and other circusy performers, including a South African troupe of dancer/drummers. A show-jumping sequence was staged as a high-spirited “competition” between the horses and high-springing humans, in contrast to an incongruously traditional solo dressage demonstration.

I was encouraged by the evident interspecies connection between the performers, and impressed, though not moved, by the eye-and-ear-boggling magnitude of the production. (Toward the end, the stage was flooded with water – environmental-consciously recycled, of course – for a big, splashy climax.) It struck me as the same kind of spectacle-creep that has been infecting Broadway for a couple of decades – technology as the obligatory salesman for art, in this case one-upping both Cirque and circus. Personally, I prefer seeing horses in a pasture and theater in a playhouse.

If you’d like to be notified of future posts, email StageStruck@crocker.com