Police brutality in places like Ferguson, Cincinnati, and New York City sparked the Black Lives Matter movement and a national debate about how police use their power to detain, arrest, and deploy potentially deadly force.

Citizens — including ones in the Pioneer Valley — sometimes find themselves on the receiving end of that power and raising questions about whether officers have gone too far.

Michael Ververis is one of them.

As the bars were letting out early one morning in January 2011 in Springfield’s entertainment district, Ververis sat in the passenger seat of his friend’s car when an officer told them to move along. He smacked the vehicle with a flashlight or nightstick, according to a lawsuit Ververis later filed against the city.

His friend asked the cop for his badge number, the lawsuit alleges. Four officers then dragged Ververis out of the sport utility vehicle, kicked him, and choked him into unconsciousness, the suit says. When he came to, he found himself being charged with disorderly conduct, assault and battery of a police officer, resisting arrest, and attempted larceny of a firearm.

Ververis was later tried and acquitted of all charges, and the city settled the lawsuit by paying out $175,000. But the case wasn’t over; questions about the officers’ conduct went before Springfield’s Community Police Hearing Board.

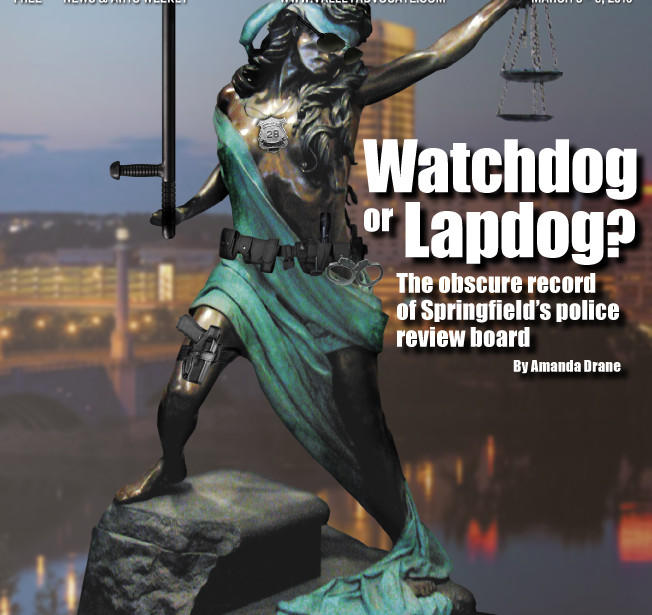

The seven-member board was created in 2010 by Mayor Domenic Sarno, largely in response to public outcry over the 2009 beating of Melvin Jones III, a black motorist struck 20 times with a flashlight by former Springfield officer Jeffrey Asher, leaving him partially blind and with broken facial bones. According to Sarno, the board has served as an important check on the power of police and should reassure the public that no complaints about police conduct go unaddressed.

“The fact that there has been civilian oversight of every single complaint involving a police officer has prohibited any complaint from being ‘swept under the rug,’” Sarno said in response to questions from the Advocate.

In the case of Ververis, the board concluded in Dec. 2011 that the officers had been guilty of misconduct in the incident earlier that year and recommended disciplinary action. But final say went to the city’s top cop, then-Police Commissioner William Fitchet, who sustained charges against all officers involved except one, ordering that all found guilty of wrongdoing receive re-training. Fitchet later sent Ververis a letter informing him that an unspecified punishment was imposed.

In too many cases, critics say, the board and police administration gloss over cases of police misconduct ranging from foul language to physical abuse. They complain that the board is made up of mayoral appointees who rely on police officers to investigate their colleagues’ work, that some citizen complaints never make it to the board, and that people in neighborhoods with heavy police presence have little faith that their allegations will receive serious and independent review.

Chelan Brown, who founded the Springfield anti-violence organization AWAKE, said there’s a rift between the residents of Springfield and its officers. Brown said she has a difficult time convincing young people to file complaints because they fear they’ll face harassment and unjustified criminal accusations.

“They have no trust in the process,” Brown said. “You go to the police department and they give you the runaround.”

A major source of distrust, said Brown and the others, is the board’s failure to live up to its pledge of public accountability. While some details of its investigations are confidential because they involve personnel issues, the board is supposed to provide an annual public report giving at least some information about the cases that come before it.

After producing those reports in its first three years of operation — a 2011 report released in May 2012, and a report combining years 2012 and 2013 released in March 2014 — the board is more than six months late in producing the report for the 183 cases it reviewed in 2014. Last week, in response to questions from the Advocate, Sarno’s office released an overview of that year’s work, some statistics about 2015 cases and a promise to provide the full 2014 report in March. Sarno said he expected the law department to release the 2015 report as well.

According to that summary, the board reviewed 183 cases in 2014, recommending retraining or disciplinary sanctions against officers in 12 cases — about 7 percent of them. In all but four of those cases, Springfield Police Commissioner John Barbieri followed the board’s recommendation. Barbieri accepted all but two of the 76 recommendations made by the board in 2015. Of the 141 total cases reviewed by the board last year, 35 resulted in retraining or disciplinary action.

The delays in providing public reports show the gap between Sarno’s promise and the board’s delivery, say critics.

“I think that the system we have is completely broken and it’s unacceptable that they haven’t issued a report in two years,” said City Council President Michael Fenton, who feels the board has adequate resources but that it’s not enough of a priority. “It’s unacceptable that there isn’t more public accountability and transparency.”

Other questions linger, including this: If the board is a public body, why are many of the meetings it holds to review cases conducted with just one or two members of the seven-member board?

City Solicitor Ed Pikula defends these meetings, saying they are an efficient way for the board to conduct an initial screening of complaints before deciding which ones to schedule for a hearing with the full board.

But records show that only a tiny percentage of complaints make their way to a full board hearing; the board held hearings on only three of the 183 cases examined in 2014, and another three out of 141 in 2015. The remaining complaints were either dismissed or advanced to the commissioner after a meeting involving only one or two members of the board.

Bill Newman, director of the Western Massachusetts office of the American Civil Liberties Union, worried that one or two board members have the power to act unilaterally on the board’s behalf.

“This strikes me as an asinine procedure,” said Newman. “It’s worse than that — it’s non procedure. This board isn’t functioning as a board. It’s operating as seven separate autonomous judges.”

Commissioner John Barbieri said that even if it’s not obvious to the public, the board puts in hard work.

“I think that the members of the Community Police Hearing Board take their roles very seriously,” said Barbieri. “They take into consideration the requirement for police personnel to serve our community respectfully while balancing the tremendous difficulties officers have policing in an urban environment.”

Pikula said that while there are some kinks to work out with increasing transparency and data collection, the biggest issue the board has is credibility not only with residents, but also with police.

“Right now you have the police who feel the board is out to get them,” said Pikula. “And you have the community — who benefits from this review, who have complaints — believing the board’s out there to protect the police.”

Policing the police

Springfield started taking steps toward civilian review in 2007, when a report conducted by Northeastern University professor and director of the Institute on Race and Justice Jack McDevitt and his associate Amy Farrell highlighted the need for accountability and laid out the basic structure for a review board.

Farrell and McDevitt produced the report at the behest of former Springfield mayor Charles Ryan, who was working to address a 2004 complaint from the Pastor’s Council of Greater Springfield with the Massachusetts Commission Against Discrimination, which alleged “that the [Springfield Police] department had engaged in a continuous pattern and practice of racially discriminatory conduct towards members of minority groups in the city.”

In response, Ryan formed the Community Complaint Review Board in 2007, at the tail end of his administration; Sarno was first elected in November of that year. That board was widely criticized as a “no-teeth” group throughout its short lifespan, until Sarno dissolved it and replaced it with the current board in February 2010, granting the new body subpoena power to use in its deliberations. With the power to hold hearings, the upgraded board is authorized to subpoena witnesses, compel evidence and attendance at hearings, administer oaths, and take testimony. Pikula said subpoena power is used by the board only sparingly.

“If you need to compel a person to testify by a subpoena, the fact that they are unwilling to testify voluntarily indicates that it will be difficult, if not impossible, to elicit favorable testimony,” said Pikula. The power to subpoena, Pikula added, comes in handy, however, with relevant records that would otherwise be unavailable.

Springfield was one of the first cities in Massachusetts to create a civilian police review board — Cambridge was the first in 1984, while Boston formed one shortly before Springfield in 2007 — and such boards are increasingly common in large cities including New York and Albany.

Last year, the Worcester City Council voted against forming a civilian review board. In the spring, Boston Mayor Marty Walsh called for an overhaul of the city’s civilian review board amidst calls for subpoena power and more resources.

Sarno asserts that the process of civilian review is still maturing. Nobody, he said, has it perfect.

“The implementation of this board, and its evolution to date show that civilian oversight and review of the investigation of complaints and use of force incidents has become a standard practice for the Springfield Police Department,” Sarno said. “The issue is no longer whether there should be civilian oversight, but rather, what type of civilian review is most appropriate for Springfield. No matter what process is followed, each will have their own strengths and weaknesses.”

How it works

People wanting to lodge a complaint of police conduct must expend some shoe leather. Because there’s no online form, residents must file their complaints in person at City Hall, the Police Department or the New North Citizens’ Council, according to board chair George Bourguignon. There are perhaps other locations where forms are provided, he added, but he’s unaware of them.

Complaints then go to the department’s Internal Investigation Unit, which launches an investigation. The results of that internal probe then go to the Community Police Hearing Board (CPHB), which decides whether to dismiss the matter, recommend a disciplinary sanction or to hold a full hearing. In addition to considering civilian complaints, supervising officers will sometimes, as in the case of Ververis, deem an incident worthy of internal review and initiate an internal investigation.

The commissioner makes the final call in all cases. Based on recent data, Barbieri accepts the board’s recommendations in almost every case.

According to the preliminary data released last week, the board reviewed nearly twice as many complaints in 2014 as in 2013, during which the board reviewed 92 cases. They reviewed 86 matters in 2012, 160 in 2011, and 136 in 2010.

Data for 2015 shows disciplinary action is on the rise; 35 out of 141 cases reviewed resulted in retraining, suspension, or another form of discipline, or about 25 percent. That’s up from 7 percent in 2014. In 2013, 14 percent of matters reviewed resulted in retraining or discipline; and in 2012 13 percent resulted in department action.

“These numbers support the fact that the CPHB has helped ensure accountability and transparency and has placed the Springfield Police Department in line with nationally accepted best practices for civilian oversight,” Sarno said in the press release.

Denise Jordan, the board’s liaison and Sarno’s chief of staff, said the city’s Law Department has been slow to produce the report “because there’s been so many things going on with [the planned casino by] MGM that there hasn’t been time.”

Window dressing?

Talbert Swan, president of the Greater Springfield chapter of the NAACP, said he’s long had serious questions about whether the police board can provide the kind of review the public will trust.

Several things trouble Swan, including the fact that all seven members are mayoral appointees, and that the board’s decisions hinge on investigations conducted by the police themselves. He said the people of Springfield should have a greater say in who sits on the board.

“We really have no real citizen’s review of police activity,” Swan said. “It’s a farce — it’s window dressing. Springfield can do better than that and should do better than that.”

Brian Rizzo, a retired New York City police officer and a criminal justice professor at Westfield State University, said that because the current system allows the department to call any number of board members in to review mounting complaints, officers are free to “cherry pick” any members who they feel treat them more favorably. He said anything less than a pre-set panel of at least three members “screams impropriety.”

He said that one board member deciding cases for the board also seems a vestige of the good-ol’-boys days.

“And that’s the thing they’re trying to get away from,” Rizzo said.

Luke Ryan, a lawyer who’s represented several clients with cases reviewed by the board, said the way it functions remains largely a mystery to him. “It’s happened before where I’ve had clients I thought were very credible who never got to have a hearing,” said Ryan.

Board Chair George Bourguignon acknowledged that the board needs to provide more public information. Six years in, he said, “we’re still trying to inform people that we exist.”

Chelan Brown said she’s tried several times to figure out how the complaint process works through the mayor’s office, city council, and the police department and has never received the information she needs to better serve her community.

“Besides [going to] the NAACP, people have no real idea what to do,” said Brown. “They don’t know what to expect and that scares people. I’ve had kids tell me that they get beat up by cops when they get pulled over — but that’s just how it is. They’re lucky to make it home.”

One complainant wasn’t even aware his complaint was reviewed by the board until a reporter contacted him for this story. He, like many others, complained about feeling disrespected when calling upon officers for help.

“I was shocked by the way [officers] responded,” said James Villalobos, 20, who filed a complaint three years ago alleging that police behaved abusively when responding to a family dispute. “They were swearing at my sister,” he said. “It kind of explains why relations are the way they are.”

Villalobos said Charles Youmans, a city police officer and his mentor, urged him to file the complaint with IIU. “I remember thinking after the incident: I’m a pretty respectful kid from Sixteen Acres so I could only imagine how people in other neighborhoods are treated. It’s pretty scary to think about.”

A couple of months after that, said Villalobos, he received a letter from former commissioner Fitchet saying the officers had been disciplined. But there were no details. “I don’t think it was adequately resolved,” said Villalobos. “There needs to be more communication.”

The most recent data available from the board shows rudeness as the leading allegation in citizens’ complaints about officers. McDevitt said that that’s not unique to Springfield; allegations of police rudeness accounts for the majority of grievances lodged statewide.

Villalobos’s complaint was one of 34 alleging rudeness in Springfield in 2013, out of 81 total complaints for the year; 26 others alleged violations of rules and regulations; 15 more pertained to hands-on use of force; five related to use of force with officers’ equipment; and one complaint alleged criminal activity.

According to city records, one of the officers involved in the incident with Villalobos had a previous complaint lodged against him for his language during a family dispute. Following the incident with Villalobos, records show his supervising officer, Capt. Cheryl Clapprood, issued a verbal reprimand in response to the complaint and reminded him of the previous one.

Early warning system

Swan, Ryan and others said it’s this kind of pattern-tracking that is one of the board’s most important functions.

“We need an early warning system,” said Swan. “We shouldn’t have had to see (Officer) Asher beating Melvin Jones before dealing with Jeffrey Asher.”

Former board member Sal Circosta said complaints about officer language were the least worrisome to him, saying he would often dismiss a complaint over foul language unless a child or an elderly person was on the receiving end.

The ACLU’s Newman, however, said that’s not right. “Here you have a police officer with his loaded gun, his handcuffs, his mace, his nightstick, his flashlight — which we know from the Melvin Jones case they’re willing to use as a weapon — screaming vulgarities,” said Newman. “That’s a lot more scary than an average person in that situation.”

Sarno said that every allegation of police misconduct gets a board review, but some community activists are unsure.

Swan said the NAACP regularly hears from people who say their complaints never went anywhere. “We’re getting some seriously conflicting information.”

Swan said that because of confidentiality issues he could not cite specific examples.

City lawyer Pikula said he is working with Sarno on revising the board’s operations to increase public faith. He said that with all the critical press the board has gotten in recent weeks due to the report’s tardiness, he hopes the community — City Council included — will be wide awake and ready to make some improvements.

“I would like to see the city council adopt the [revised] executive order as an ordinance,” said Pikula. “To make clear the board’s authority in all respects, whether it is power to subpoena records or acknowledgment that there are civilian eyes reviewing every complaint made to this department can only help to improve things.”

Contact Amanda Drane at adrane@valleyadvocate.com.