Last November, fish biologists working at an undisclosed location in the Farmington River watershed came across three mounds of stones. Ordinarily, this discovery wouldn’t have been particularly significant. But mounds like these, filled with tiny orange eggs, had not been seen at the watershed — which stretches from southern Hampden County into central Connecticut — in over 200 years. The biologists recognized them as salmon nests, or redds, which meant that Atlantic salmon had spawned in a tributary of the Connecticut River. There have been a handful of similar reports since the species was wiped out here in the early 1800s, but the last documented redd was found in the Salmon River, another Connecticut River tributary, in 1991.

In December, in celebration of the discovery, the biologists posted their findings to Facebook. This led to some hopeful — but misleading — media coverage. Many speculated that a 45-year program to restore salmon to the Connecticut River, which was cancelled in 2012, may yet pay dividends.

As it turns out, the causes for celebration are as few as the salmon themselves.

“Everybody wants to make this into this wonderful recovery story, this story of rebirth, and it’s not,” says Steve Gephard, a fish biologist for the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection. He’s a leading expert on Atlantic salmon in the Connecticut River — and the author of that Facebook post.

“This has been blown out of proportion,” he says. “Lots of people have made comments … saying, ‘Wow, there’s still hope for Atlantic salmon in the Connecticut River. The restoration is finally showing progress.’ Bullshit. The restoration program has been cancelled.”

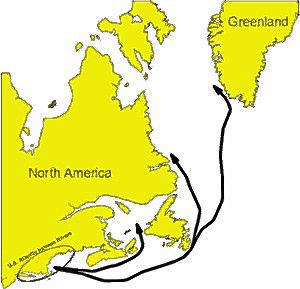

The truth, according to Gephard and Ken Sprankle, Connecticut River coordinator for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, is that the discovery of the redds likely heralds a last hurrah for the iconic fish, at least in the Connecticut. The last major stocking event of Atlantic salmon young, or fry, took place in 2013. Since the fish typically spend about two years in fresh water and an additional two in the Atlantic Ocean off of Greenland before returning home, their occurrence in the Connecticut after 2017 will be exceedingly rare.

In its heyday, the program raised fry by the millions and released them into tributary streams, only to see a handful of spawning adults returning to the river each year. A couple of wild salmon redds seem unlikely to succeed where the massive restoration program failed. So how is it that a 45-year program that returned millions of fish to the wild each year was simply unable to help the Atlantic salmon population rebound?

The answer is complicated. A dizzying array of factors are responsible for the decline of the Atlantic salmon — not all of which which were recognized at the program’s inception — the most significant of which are the damming of rivers, water pollution, and climate change. Efforts to pass fish upstream using fish elevators or fish ladders have produced mixed results. During the same period of time, populations of other fish species, like the American shad, were able to achieve some success in maintaining a stable population.

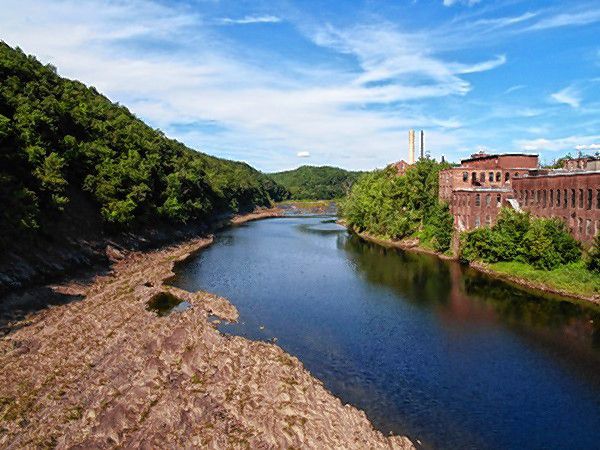

Prior to the Industrial Revolution, the Atlantic salmon runs totaled in the tens of thousands, while American shad could run in the millions. Atlantic salmon originally disappeared from the river in the early 1800s because of the damming of the Connecticut — which was originally meant to facilitate barge navigation of the river and eventually led to hydropower — and because of the absence of effective fish passage facilities.

But a significant American shad run persists, although it is greatly diminished. Shad are able to spawn in the mainstem river, whereas salmon need to reach smaller coldwater tributaries further upstream in order to successfully reproduce.

For behavioral reasons, American shad tend to be fickle with regard to the fishways they’re able to pass. However, fishways that pass American shad successfully are always effective at passing other fish species. For this reason, the American shad has been the focus of scientists that study fish passage.

Better research and technology have led to ever-improving fish passage, but issues remain. Not all fishways are created equal. For example, the fish ladder at Turners Falls has been an abysmal failure by all accounts. U.S. Fish and Wildlife figures show that an annual average of less than five percent of total fish that are passed in Holyoke are passed at Turners Falls, which is 37 miles upriver.

“We pass a lot of fish at Holyoke,” Gephard says. “On the other hand, Turners Falls sucks … it’s very, very disappointing. A relatively small percentage of the fish that pass through Holyoke move up through Turners Falls. Meanwhile, the next fishway up in Vernon, Vermont, works really well. They pass almost all of the fish that come through Turners Falls. … When you see that 80 to 90 percent of the fish that come through Turners Falls go through Vernon, it shows that these fish still have stamina and still have the ability.”

Five hydroelectric facilities in the Connecticut River watershed area, including Turners Falls, are currently in the midst of relicensing for 2018. Under section 18 of the Federal Power Act, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has the right to prescribe improvements to fish passage prior to relicensing. Under that measure, Gephard says that FirstLight Power Resources, the operator at the Turners Falls dam, will be installing a fish elevator like the one in Holyoke to improve American shad passage.

Salmon and other species may benefit from measures to improve downstream passage and increase repeat spawning as well. Holyoke Gas and Electric recently completed a major construction project on the dam aimed at improving downstream passage, which may help salmon, as well as other fish species that migrate upriver, to spawn a second or even a third time.

Despite improvements, fish passage has its fair share of critics. A 2013 paper published in the journal Conservation Letters called fish passage a “half-way technology” and argued that the restoration of migratory fish populations to historic levels would be impossible without the removal of dams. Sprankle and Gephard agree with the assessment that dammed rivers will never be as good for wildlife as unimpeded rivers. But according to Sprankle, the development of fish passage facilities is an “iterative process” which keeps improving.

“It’s unfair and inaccurate to say that fishways cannot work,” Sprankle says. “There are serious issues that exist on large-scale fishways [across the nation]. There are clearly significant issues. But that’s not to say that you should totally discount … these hydropower facilities. If you want to be pragmatic, you can’t assume that you’re going to have all the dams taken out in these rivers.”

It may seem great that the Connecticut’s fish have increased access to their historical habitats. But not so fast. While Gephard and Sprankle are cautiously optimistic about the next fifty years when it comes to American shad, they’re not holding out any hope for the Atlantic salmon in the Connecticut. The reason probably won’t surprise you.

“When we first started trying to restore fish populations in the 1960s,” Sprankle says. “No one was thinking about climate change.”

Nor could they have predicted the dire result it would have on the Atlantic salmon. The Connecticut River is at the very southern end of the salmon’s native range. The shad in the Connecticut, on the other hand, are right in the middle of theirs, rendering them better equipped to deal with the climatic changes underway.

Warming ocean temperatures, Gephard says, have led to the melting of ice caps, which in turn disrupts global ocean currents. These currents affect not only weather patterns but the movements of marine organisms. The current that Atlantic salmon swim against on their journey to the Labrador Sea is becoming stronger and colder as a result. In turn, warming southern waters have drawn exotic predators and competitors north, throwing the northern oceans into ecological bedlam and further diminishing survival prospects for salmon. To top it all off, a perfect storm of partisan politics has paralyzed restoration programs in the U.S., making funding increasingly hard to come by.

Taken together, these factors are the death knell for the Atlantic salmon in the Connecticut. While it is not inconceivable that salmon may one day swim as far north as the headwater lakes of northern New Hampshire, the prospects for such a recovery remain dim.

Andrea Donlon, the Massachusetts river steward for the Connecticut River Watershed Council, says the organization doesn’t support the cancellation of the salmon restoration program, but understands the criticism.

“We were always supporters of it,” Donlon says. “We felt like restoring salmon was also good for other species, so the effort to restore salmon meant better fish passage [and] attempts to take down dams … We understood people’s criticism of the costs that went into it for the benefit that came back, in terms of the numbers of fish. It’s just unfortunate that it was sort of an all-or-nothing thing.”

In Massachusetts, resources for the salmon restoration program have been reallocated. The former salmon hatchery in Sunderland will now serve as a breeding and research facility for the endangered puritan tiger beetle. Connecticut’s legacy program still perseveres, distributing salmon eggs to classrooms so that school children can hatch them and distribute them to streams.

The greatest legacy of the salmon program may not be the contributions it made to the recovery of the Atlantic salmon, but the improvements it spurred in fish passage facilities. It seems that for the foreseeable future, we are likely stuck with hydroelectric dams. And while the technology is still imperfect, improved passage is likely to benefit the host of other migratory fish that utilize the Connecticut and its tributaries each year.

Still, suggestions that the salmon program could, or should, be revived are misguided. Gephard, who has spent his entire career on the salmon program, sums it up this way:

“Had we been able to get it started a couple years earlier, before the downturn in the Atlantic Ocean occurred, maybe we’d have met with some success. But as things are now, the conditions in the Atlantic Ocean are horrible. The conditions in government funding are horrible. Between the lack of money and the poor survival rates in the Atlantic Ocean, as much as I like that program, it just doesn’t make sense.”•

Contact Peter Vancini at pvancini@valleyadvocate.com.