At the end of Act One in Shakespeare’s play, Othello is dispatched from Venice to command the garrison on the island of Cyprus, a strategic outpost on the eastern rim of the Mediterranean that is under attack from the Turkish fleet. So although he’s “the Moor of Venice,” Othello’s tragic fall, spurred by “the green-eyed monster” jealousy, takes place not in that canal-threaded city-state, but in an seaside fortress overlooking a deep blue harbor and on the busy cobbled streets at its foot.

Last month I had the thrill of standing high on the Venetian Wall abutting “Othello’s Castle” in the Cypriot town of Famagusta. I could just imagine Othello’s bride, Desdemona, looking out from those ramparts for the arrival of his ship, and the general himself atop the citadel, mad with heartbroken fury.

Last month I had the thrill of standing high on the Venetian Wall abutting “Othello’s Castle” in the Cypriot town of Famagusta. I could just imagine Othello’s bride, Desdemona, looking out from those ramparts for the arrival of his ship, and the general himself atop the citadel, mad with heartbroken fury.

I was in Cyprus with my partner, Naomi Miller, who was speaking at The Othello’s Island Conference, an annual gathering of Renaissance scholars. Her talk focused on Shakespearean adaptations and re-visionings that give “a local habitation and a [new] name” to the originals’ plots and themes, “as imagination bodies forth the forms of things unknown” – as another of Shakespeare’s characters put it. Modern-day riffs on Othello include plays by Toni Morrison and Paula Vogel that take Desdemona’s point of view and Afro-Canadian playwright Djanet Sears’ Harlem Duet, which recasts the tragedy in an all-black world.

Othello’s Castle has only taken on that name since the British – last in a long line of imperial powers – occupied Cyprus in the 19th century. The fortress is a Renaissance-era descendant of the original stronghold built in the 1300s by the Prince of Tyre (not the same Prince of Tyre as Shakespeare’s Pericles), expanded and fortified under Venetian rule. Though Othello is pure fiction, it’s possible the character was suggested by a Venetian governor of Cyprus in the early 16th century, one Cristoforo Moro, whose surname is Italian for Moor.

Cyprus also reminded me of other Shakespearean plays: Romeo and Juliet, about “two households, both alike in dignity,” sharing one town but divided by ancient enmities; King Lear, about a partitioned kingdom; Henry V, about a battle over disputed territory. For Cyprus is an island divided, its capital city, Nicosia, split in two and marked by international checkpoints.

About two-thirds of the island is a Greek-speaking member of the Eurozone, while the northern segment is occupied (in both senses) by a putatively independent country whose language and currency are Turkish and is in all but name a Turkish province. This unhappy division arose from longstanding rival claims on the island by Greece and Turkey and clashes between ethnic Greek and Turkish Cypriots that began almost immediately after the end of British rule in 1960.

These came to a head in 1974, when a coup intended to unite Cyprus with Greece was met by a Turkish invasion, leading ultimately to a political division enforced by a United Nations buffer zone. An island-wide referendum on a proposed two-state federation was rejected by the Greek Cypriot majority in 2004.

These came to a head in 1974, when a coup intended to unite Cyprus with Greece was met by a Turkish invasion, leading ultimately to a political division enforced by a United Nations buffer zone. An island-wide referendum on a proposed two-state federation was rejected by the Greek Cypriot majority in 2004.

You have to show your passport at the Green Line separating the two sides, but otherwise the border is porous and relations are strained but cordial. We stayed in the Greek section of Nicosia but crossed into Northern Cyprus several times, including on our way to Famagusta.

In 2014, after years of neglect, Othello’s Castle was renovated under an EU-sponsored program spearheaded by a coalition representing both communities. It reopened last summer with an on-site performance of Othello featuring a mixed cast of Greek and Turkish Cypriots – a dramatic statement of the desire for resolution. And last year talks aimed at reconciliation, if not reunification, began again.

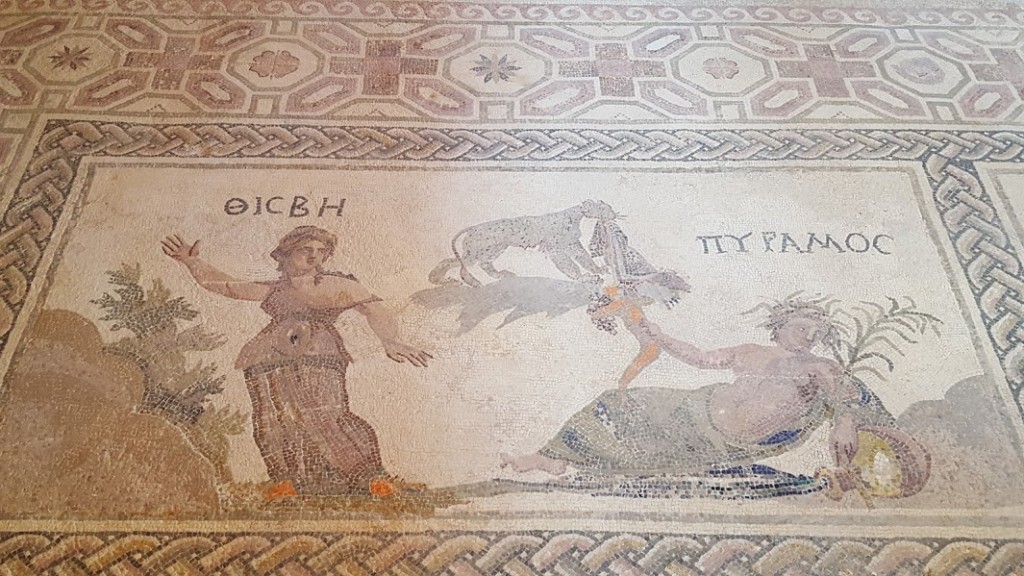

More Shakespearean echoes sounded in a day trip to the other end of the island from Famagusta – Paphos, where they say the goddess Aphrodite floated ashore on that clam shell.  The Archaeological Park at Kato Paphos contains evidence of centuries of Greek and then Roman occupation. We skirted the remains of a Roman villa known as the House of Theseus – he’s the one who extols “the poet’s pen,” which “gives to airy nothing a local habitation and a name” in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Then, looking down at the carefully restored mosaic floors in the House of Dionysus, we spotted another resonance from that play: a depiction of Pyramus and Thisbe, the lovers whose tragic tale is comically enacted at the celebration of Theseus’ wedding to the Amazon Hippolyta.

The Archaeological Park at Kato Paphos contains evidence of centuries of Greek and then Roman occupation. We skirted the remains of a Roman villa known as the House of Theseus – he’s the one who extols “the poet’s pen,” which “gives to airy nothing a local habitation and a name” in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Then, looking down at the carefully restored mosaic floors in the House of Dionysus, we spotted another resonance from that play: a depiction of Pyramus and Thisbe, the lovers whose tragic tale is comically enacted at the celebration of Theseus’ wedding to the Amazon Hippolyta.

The site also contains a Roman odeon, a semi-circular mini-amphitheater built from limestone blocks, seating 1200 and still used for musical and theatrical performances.  Just above it, overlooking the sea, is a gleaming white 19th-century lighthouse. Seeing that ancient/modern juxtaposition, I imagined 2nd-century actors on that stage performing, perhaps, the Plautus farce that Shakespeare would one day turn into The Comedy of Errors. And I thought of the generations after generations of performers throughout the world, whose talents and imaginations have “bodied forth” that most ephemeral, and at the same time most enduring art form: theater.

Just above it, overlooking the sea, is a gleaming white 19th-century lighthouse. Seeing that ancient/modern juxtaposition, I imagined 2nd-century actors on that stage performing, perhaps, the Plautus farce that Shakespeare would one day turn into The Comedy of Errors. And I thought of the generations after generations of performers throughout the world, whose talents and imaginations have “bodied forth” that most ephemeral, and at the same time most enduring art form: theater.

If you’d like to be notified of future posts, email StageStruck@crocker.com