Three of the four shows I saw at the National Theatre in London last month were star vehicles, and the fourth one’s ensemble cast featured a very well-known face. The first three also, coincidentally, ended in sudden reprieves from ignominious deaths.

Another symmetrical coincidence: We were at the National on the very first night of our UK visit, and at the Amherst Cinema on the first night after our return for yet another treat from Britain’s flagship theater, courtesy of NT Live.

More on that one below. But first, London.

The Threepenny Opera is a new translation of the Bertolt Brecht/Kurt Weill musical, a politically charged satire set in a fanciful Victorian London, about a family business employing an army of ragtag beggars, a criminal gang led by a charming cutthroat, a forbidden love triangle, and a whore with a heart of tarnished gold. Simon Stephens’ adaptation captures the spirit of Brecht’s jauntily caustic script and lyrics, and an eight-piece band, part of the onstage ensemble, does justice to Weill’s Weimar jazz amalgam of melody and dissonance.

The production is muscular but loose-limbed, wearing its working-class politics unapologetically and making plenty of space for humor. Brecht’s fourth-wall-smashing Epic Theater style is loyally evoked with touches like scenery that’s changed as part of the action and labelled, for instance, Big flag for scene 7.

The production is muscular but loose-limbed, wearing its working-class politics unapologetically and making plenty of space for humor. Brecht’s fourth-wall-smashing Epic Theater style is loyally evoked with touches like scenery that’s changed as part of the action and labelled, for instance, Big flag for scene 7.

Rory Kinnear, who has previously played Hamlet and Iago at the National, is a rough-diamond Mack the Knife, ruthlessly charming and disarmingly ruthless. Rosalie Craig, whom NT Live audiences saw this past season as Shakespeare’s Rosalind, is effectively brassy as Macheath’s newly wedded wife, daughter of the Faganesque Mr. Peachum and his sluttish missus (Nick Holder and Haydn Gwynne), though her transition from naïve bride to hard-headed accomplice is implausibly sudden. Sharon Small, whom you might remember as Inspector Lynley’s sidekick in the Mystery! TV series, plays Jenny Diver, Mack’s drug-addled sometime lover who unwillingly turns him in.

At the end of Threepenny, Macheath, sentenced to hang for his crimes, is miraculously reprieved in a gleefully sarcastic climax. At the beginning of The Deep Blue Sea, the central character is rescued from near death after a suicide attempt.

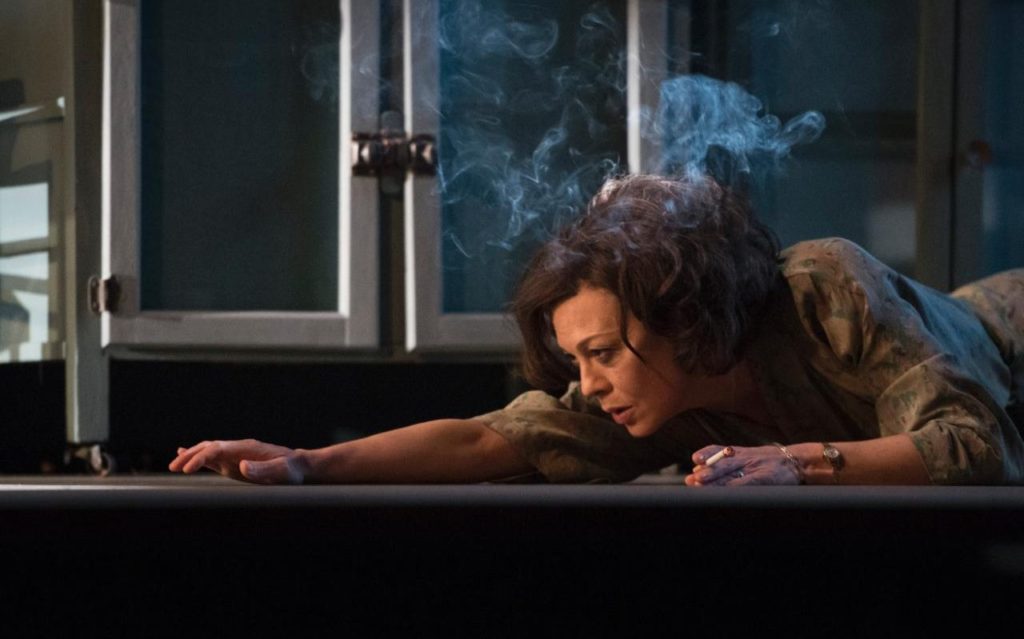

She’s Hester Collyer, played by Helen McCrory, who was most recently seen on the National’s stage as Medea (and currently on the BBC and Netflix in Peaky Blinders), and Hester’s situation is oddly akin to that of Euripides’ tragic heroine. Having abandoned a comfortable existence for an obsessive infatuation, she’s now ignored and demeaned by her new lover. One of her first lines might well come out of Medea’s mouth, as she sums up her feelings of “anger, hatred and shame, in equal proportions.”

But this is no Greek tragedy. Terrence Rattigan’s 1952 drama takes place in a shabby London flat, Hester is no royal princess but the estranged wife of a judge, and her paramour is no adventuring Jason but a handsome ex-test pilot who’s lost his nerve and taken to the bottle.

But this is no Greek tragedy. Terrence Rattigan’s 1952 drama takes place in a shabby London flat, Hester is no royal princess but the estranged wife of a judge, and her paramour is no adventuring Jason but a handsome ex-test pilot who’s lost his nerve and taken to the bottle.

McCrory is magnificent, a consummate performer whose every glance and gesture is charged with meaning. But the material is creaky, a labored psychological study of a soul in torment that fails to make her life-and-death obsession believable (and Tom Burke’s bland performance as the feckless lover doesn’t help) and which introduces irrelevant plot fillers that in a whodunit would be red herrings.

Elizabeth McGovern’s name isn’t featured in the blurbs for Sunset at the Villa Thalia, but her face is by far the most widely recognizable of any in the National’s current season. She played Cora, the American-heiress wife of Lord Grantham, in Downton Abbey.  Here, in a Gidget-blonde wig, she’s June, the doggedly loyal wife of State Department (read: CIA) officer Harvey, an amiable bully played by Ben Miles.

Here, in a Gidget-blonde wig, she’s June, the doggedly loyal wife of State Department (read: CIA) officer Harvey, an amiable bully played by Ben Miles.

This new play by Alexi Kaye Campbell takes place on a Greek island at the beginning and end of the repressive Regime of the Colonels, 1967 to 1974, which was ushered in by a CIA-sponsored coup that foreshadowed other right-wing takeovers in Latin America. It’s a metaphor, really, of American global arrogance and power, in which a young English couple are bulldozed by the pushy Yank into buying a small villa from destitute locals at a knockdown price. Regrets and recriminations ensue, with ghosts real and implied haunting the place and June bridging her conflicted ethics and allegiance with cocktails.

While the script’s allegorical resonance becomes increasingly schematic, the production, in the National’s newly refurbished and rechristened Dorfman Theatre, retains a dramatic honesty with affecting performances, especially by McGovern and Miles, as well as Glykereia Dimou as the villa’s rightful young heir, whose future is wrecked by the intruders’ thoughtless and ultimately cruel sense of entitlement.

If The Threepenny Opera looks at the plight of the poor and their coping strategies though a historical lens, The Suicide (funny how these themes keep recurring) places it in a thoroughly contemporary and wildly farcical frame. Suhayla El-Bushra’s play, based ever-so-loosely on a Soviet-era satire, concerns Sam Desai, an out-of-work Londoner so down on his luck he decides to do away with himself. (As he explains it, “I’m not unstable – my life is shit, that’s all.”)

When his intention is broadcast on social media, he’s immediately besieged by well-wishers – wishing, that is, for his demise, in order to advance their own agendas: the harried social worker to prove she needs a bigger budget, the spiteful local politician (her ex) to prove her incompetence, the café owner who hopes her Last Supper gala will save her failing business, the rap poet whose elegy makes him a YouTube star, and others equally driven by faux-compassionate self-interest.

And where Threepenny insists on its very theatricality, its happy ending pointedly not like real life, most of The Suicide’s characters treat their real lives as performance, public figures in a social-mediated world.  At the online news of Sam’s impending suicide, they become his would-be scriptwriters, making themselves the stars of his story. Ironically, Sam’s intended solution to being an abject failure makes him a celebrity.

At the online news of Sam’s impending suicide, they become his would-be scriptwriters, making themselves the stars of his story. Ironically, Sam’s intended solution to being an abject failure makes him a celebrity.

The popular British comedian Javone Prince plays Sam with a growing sense of confusion and alarm. The topic – and the title – may signal pathos (suicide among young men of color is a growing concern in the UK as it is here) and the playwright’s core aim is social critique, but the play and its performers are fall-down funny. It may, like Sunset, be over-obviously schematic and the characters easy stereotypes, but its pell-mell velocity is joyous and often surprising, including a moment of nudity by the performer you’d least expect.

Perhaps most gratifying, the piece is peopled with biracial characters and interracial relationships, a fact of which absolutely no mention is made. In this community it’s just a given. At this knife-edge moment in both Britain’s history and our own, that’s inspiring.

While Sam Desai’s answer to being down and out is suicide, Francis Henshall’s is frantic improvisation. He’s the hero/clown of One Man, Two Guvnors, a runaway hit for the National Theatre five years ago, now getting an eagerly awaited encore showing in the NT Live series of HD broadcasts.

It’s a literally laugh-a-minute adaptation of Carlo Goldoni’s Commedia dell’ Arte classic The Servant of Two Masters, updated to 1963 London on the cusp of Beatlemania, featuring a live skiffle/Merseybeat band along with a hilariously escalating sequence of sight gags and a jaw-dropping master class in audience participation. It is, in a word, the funniest play I’ve ever seen.

That’s due to Richard Bean’s script, which gleefully mines the inventory of comic archetypes, the era’s smutty nudge-wink humor and the corkscrew plotting of classic farce; to Nicholas Hytner’s ingenious staging, at once freewheeling and clockwork-tight; and above all to James Corden’s pyrotechnic performance, for which he won a virtually unanimous Tony when the show moved to Broadway and which earned him the emcee spot at this year’s awards ceremony.

Corden’s Francis is an unemployed, chronically hungry but endlessly resourceful Cockney who in one frenetic day picks up two gigs as a “minder,” one to a gangster (actually the man’s sister in disguise) and the other to the upper-class twit who has accidentally killed the gangster and is in love with the sister. (And that’s probably more of the blissfully silly plot than you need to know.)

Corden’s Francis is an unemployed, chronically hungry but endlessly resourceful Cockney who in one frenetic day picks up two gigs as a “minder,” one to a gangster (actually the man’s sister in disguise) and the other to the upper-class twit who has accidentally killed the gangster and is in love with the sister. (And that’s probably more of the blissfully silly plot than you need to know.)

Corden’s crafty if reckless hero bounces between confusion, panic and seat-of-the-pants invention, sprinkled with ad libs (both fake and spontaneous) and fueled by a running commentary with the audience in breathless complaints and sly conspiratorial grins. It’s a comic masterpiece with absolutely no socially redeeming features. If you can’t make it to London for a National Theatre show this week, there’s a matinee screening of this one at the Amherst Cinema on July 9th.

Photo credits: Alastair Muir, Richard Hubert Smith, Manuel Harlan, Johan Persson,

courtesy of the National Theatre

If you’d like to be notified of future posts, email StageStruck@crocker.com