When I was a younger man, I looked at my father’s record collection as if it were a collection of lost gospels. He was a Dylan nut who branched out to collect lesser-known folk types, and while my friends were keeping up with what was happening in our own time, I often found myself tangled up in attempts to decipher some lyrical knottiness that promised (even if it didn’t always deliver) to enlighten me about some deeper truth.

I caught up with my own times eventually, but I’ve never quite shaken the sense that music has never meant as much as it did in the ’60s and ’70s. Certainly, today is a different world entirely, and the wild democratization of music-making and distribution has forever altered the landscape — and very much for the better, I believe. But when my dad went off to college, he was the only person on his dormitory floor who owned a turntable; when a new album came out, everyone gathered in his room to listen.

In a way, it was the very limitations of that earlier era of the industry (fewer choices for listeners, difficulty in finding new releases, etc.) that made music so very important, so politicized, and such a part of so many people’s identities.

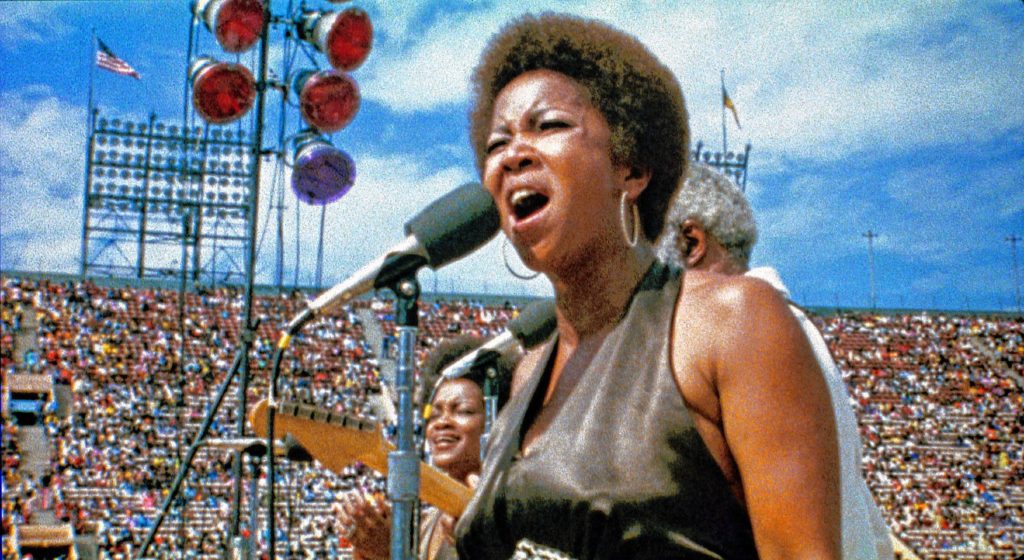

For much of America, the culmination of that idea would come with Woodstock. But for a richer understanding of the ’60s/’70s milieu, it is hard — very hard — to beat the experience of Wattstax. The 1973 concert film, screening at Amherst Cinema on Thursday, July 7 at 7 p.m., is a chronicle not just of the fabulous concert that gives the film its title — staged by famed soul label Stax Records and stacked with an amazing roster of performers, the 1972 show would draw over 100,000 predominantly black concertgoers to the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum — but also of the world surrounding the show.

Director Mel Stuart (best known as the director of the 1971 Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory) sent his crews out into the neighborhoods of Watts to interview everyday people in barbershops, churches, and a local nightclub, where Stuart filmed a relatively unknown Richard Pryor for hours on end as the comedian laid bare the state of race relations in America (it was just a few years earlier that Watts had been the epicenter of devastating riots sparked by racial tension). It seems somehow exactly right that the man who helped Gene Wilder bring Dahl’s iconoclastic Wonka so vividly to life was also the man who captured Pryor on the verge of bringing his dangerous wit to the American living room.

The concert — which was branded as the “black Woodstock” — proved both eclectic and electric. Performers included the Staple Sisters, the Bar-Kays, Albert King, and Isaac Hayes, whose film-ending performance, originally cut due to a rights beef, has been restored for this release. Further restoration was done to the film’s audio, which was completely remastered from the original concert tape.

The result is a look back that is never just a time capsule. Instead, Wattstax continues to sound a clarion call, showing us even now that the power of music to bring us together is not simply a call to dance and celebrate, but also a call to question, a call to resist, and a call to heal.

Also this week: in dueling Sunday shows, two other films turn their lens on the power of music. At 2 p.m. at local Cinemark theaters (with an encore show on Wednesday), the 1952 classic Singin’ in the Rain unspools, spinning a tale of Hollywood’s big change, in the late 1920s, from silent film to talkies. Gene Kelly stars as Don Lockwood, the star who finds his big break as his partner finds her own star falling in the new era.

And back at Amherst: Matthew Bourne’s The Car Man, directed by Ross MacGibbon, goes off at 1 p.m. A dance show specially conceived for cinema screens, Bourne’s show is loosely based on Bizet’s opera Carmen. But here the 19th-century Spanish cigarette factory is transformed into a greasy car-stop in 1960’s America, in an insular town torn apart by a stranger’s arrival. Filmed live at Sadler’s Wells Theatre in England in August 2015, The Car Man aims to bring something fresh to today’s screens.

Jack Brown can be reached at cinemadope@gmail.com.

Images: Wattstax courtesy Fantasy Inc.