“The truth is stirless,” our yoga teacher recites during a moment of closed-eye silence.

Seconds later, a boisterous squirrel in an overhead tree knocks loose something heavy. A cone-like fruit lands with a thud between my face and my neighbor’s, and we jump reflexively.

But this is yoga. We shake off extraneously plant matter, breathe in deeply, and once again close our eyes.

Other force — may be presumed to move — This — then — is best for confidence — When oldest Cedars swerve.

In the moment, I take the stanza from Emily Dickinson to mean that the truth may be stirless, but not much else is.

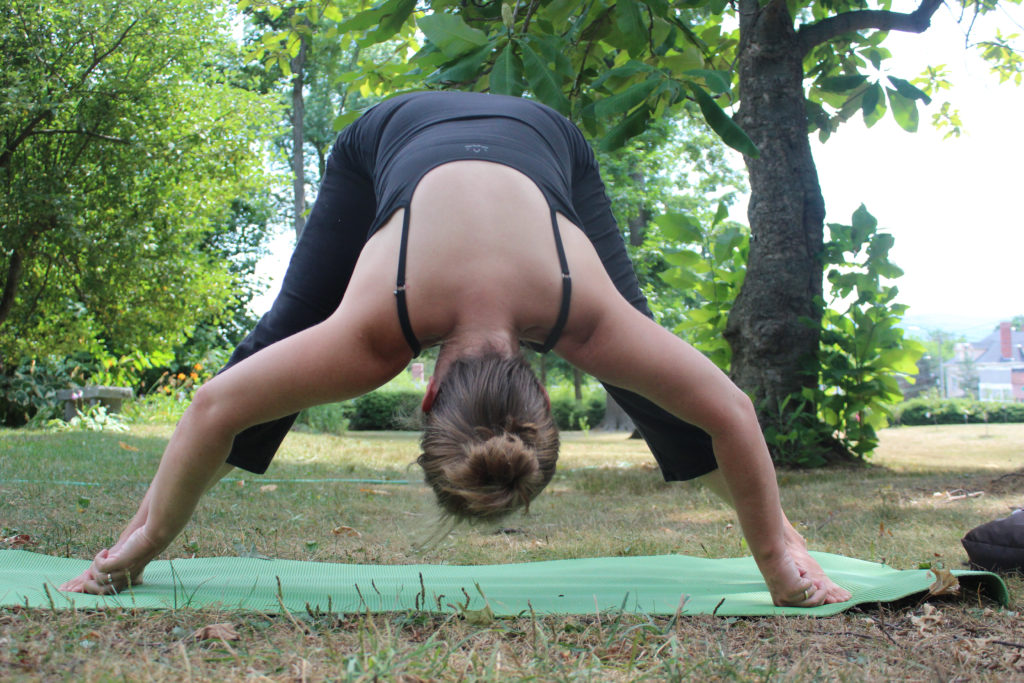

As we move through an asana at the edge of Dickinson’s famous garden, cars zoom along Amherst’s Main Street. Choruses of cicadas seemingly engage in call and response from within the trees towering above us. I resist the urge to jump out of my skin as a spider crawls up my arm and onto my chest — for the third time.

This yard, this garden — these critters, whom she called “Nature’s People” — are the way Dickinson experienced the world, and therefore created her famous works. The way the earth outside her home teems with life provides a window into what the famous recluse was seeing as she wrote her verses.

“She uses these living things out there to explain the inner workings of her own mind, you could argue,” says Michael Medeiros, public relations coordinator for the museum. “It was kind of a meditative place for her.”

Many yoga teachers stretch reality in their efforts to inspire motion — ‘touch the ceiling with your fingers,’ ‘or open your heart toward the sky’ — but few explicitly meld them together into a series, like the one held on Saturdays from 10:30 a.m. to 11:45 a.m. through August 20.

The series, say museum coordinators, was inspired by Dickinson’s use of the garden as an expansive space.

“I don’t think anyone was doing downtown yoga in 1855, but she was stretching the bounds of her imagination from the beginning,” says Medeiro of Dickinson. “Isn’t that what we want from yoga sometimes?”

Yoga Center Amherst co-owner Matthew Andrews instructs the series, using a poetic style of instruction. The style, he says, is not unique to the series.

“Feel the lungs pouring down through the shoulder girdle,” he says, as we hinge at the waist and hang our arms toward the grass. “You and the earth, pulsing and breathing together.”

We’re New England yogis, so naturally we’re used to doing yoga indoors. The earth is uneven, and it sends us tumbling. Andrews’ voice is lost in a chorus of nearby cicadas. Plant matter falls on our faces as we try to lose ourselves in cevasana. I can almost feel Dickinson among us, watching and laughing at our awkwardness.

“I was reared in the garden, you know,” Dickinson wrote in a letter from 1859.

As the class progresses, the lines between yoga and poetry begin to blur and boundaries between creature and body dissolve. Andrews reminds us to breathe — “how amazing that the air you breathe feeds the trees” — just before launching into a recitation of Dickinson’s “Air has no Residence, no Neighbor.”

Andrews seamlessly integrates instruction with prose, but chooses the verses at random before class based on “what grabs me.”

He says the beauty of the practice — in this garden and elsewhere — is to move the body from the inside out, downplaying outerworldly distractions.

“It’s not about being on the cover of Yoga Journal,” says Andrews.

Thank Dickinson that’s not the case, I tell myself, as I leave with leaves stuck in my hair.

Contact Amanda Drane at adrane@valleyadvocate.com.