If you caught much of the Rio Olympics this summer, you may have noticed a blitz of sports beverage commercials featuring Olympic athletes like boxer Shakur Stevenson swilling fluorescent blue Powerade, or Usain Bolt and Serena Williams pushing Gatorade. Aside from a heavy-handed dose of inspirational words and imagery, the ads have something else in common. They both seem to be directed at kids, with child actors portraying the athletes’ younger selves.

For Powerade, it’s part of their “Just a Kid” advertising campaign aimed at attracting the next generation of aspiring Olympians to its product. Gatorade, which has been advertising to kids since its “Be Like Mike” campaign debuted 25 years ago, ran ads featuring Usain Bolt and Serena Williams being coached by childhood versions of themselves. The implication is clear: if you want to become a successful athlete, sports drinks can help get you there. But are they really the kind of thing kids should be consuming if they hope to go for the gold one day?

Soft drink sales are at a 30-year low in the U.S., but a study from the Beverage Marketing Corporation shows that the “refreshment beverage market” expanded in 2015, due in large part to increases in demand for lower-calorie, healthier options.

Dr. Samuel Headley is a professor of exercise science and sports studies at Springfield College. He’s been teaching sports nutrition for over 20 years.

“I laugh when I see these little kids coming into the gym with a bottle of Gatorade for a basketball game that’s lasting 32 minutes,” Headley says. “But they’re bringing in their Gatorade bottle because they see Kobe on TV promoting it.”

Sports drinks like Gatorade and Powerade, Headley says, are formulated to help endurance athletes stay adequately hydrated during long periods of demanding physical exercise — not for brief bursts of activity. They contain electrolytes — like sodium and potassium, which help the body absorb and retain water — and carbohydrates, which help athletes keep energy levels up and avoid the “crash” that comes with a drop in blood sugar.

According to Dr. Melissa Roti, director of the exercise science program at Westfield State University, sports drinks just aren’t the right choice for the non-athlete.

“It’s no different than having a soda or drinking juice. It’s extra calories, extra stuff that they don’t need,” Roti says. “Ultimately, they’re more appropriate to be consumed by someone who’s exercising.”

Headley and Roti are both adamant that sports drinks are a valuable asset to competitive athletes, but suggest a simple rule of thumb: for periods of exercise that last less than one hour, water is the preferred beverage. If you’re not exercising for over an hour, the carbohydrates and sodium that you’re already getting from your daily diet are sufficient. In terms of post-exercise recovery, Roti says that your best bet is to eat a hearty meal within two hours of ending your workout.

So what about hydrating during exercising? It may seem like a no-brainer to many of us, but the recommendations for sports hydration have changed a surprising amount over the years. As recently as the 1970s, marathoners were advised to avoid hydrating altogether. In 1996, the American College of Sports Medicine — considered the authoritative body on the subject of sports medicine by professionals — was advising athletes to drink as much as they could tolerate. Then in 2007, that was rolled back to 0.4 to 0.8 liters per hour.

“If you go back in history with Gatorade,” Headley says, “one of the messages that came out of that system was that you needed to drink beyond your thirst, meaning don’t just drink until you quench your thirst, but drink even when you don’t feel thirsty.”

Headley declined to comment further on the influence of the beverage industry on sports medicine.

According to a July 2012 issue of the journal BMJ (formerly the British Medical Journal), which focused on the science behind sports drinks, the science doesn’t support the claim that athletes should drink beyond their thirst. One article, titled “Mythbusting sports and exercise products” cited claims made on sports drink manufacturers websites at the time:

Gatorade says “Your brain may know a lot, but it doesn’t know when your body is thirsty. You need to drink during exercise before you feel thirsty in order to get enough fluids in your body to maintain your performance level.” Powerade advises customers that “To avoid dehydration … you should drink before, during, and after sport” and that, “You may be able to train your gut to tolerate more fluid if you build your fluid intake gradually.”

Claims like these had become conventional wisdom in the world of athletics in no small part because of the beverage industry. It started because of the way the body’s thirst mechanism works. Headley and Roti explained that there’s a lag between when we start to dehydrate and when we start to feel thirsty. The sensation of thirst is brought on when receptors in the hypothalamus — the part of our brain responsible for telling us when we’re tired, hungry, or thirsty — respond to a thickening of the blood due to fluid loss through sweat. If the fluid isn’t replenished, it can lead to dehydration, resulting in decreased physical and mental performance. Hence, athletes should drink even when they don’t feel thirsty, the industry said, just to stay ahead of the curve.

This idea remains controversial to many in sports medicine, but there is research to suggest that slightly dehydrated athletes actually perform better. A 2011 paper published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine found that athletes who hydrated according their level of thirst performed significantly better than those who drank beyond or below it. In fact, the study showed that athletes who were dehydrated up to 2.3 percent of their body weight performed significantly better than those who were more hydrated.

The 2012 issue of BMJ mentioned earlier also ran a scathing investigative piece called “The truth about sports drinks” by Deborah Cohen, which claimed that scientists who were paid by sports beverage companies to research hydration were also responsible for guiding policy within sports medicine organizations.

Sports drink manufacturers have set up research institutions — like the Gatorade Sports Science Institute, founded in 1985 — which funded extensive research into sports nutrition and exercise science. The report says that some of the most influential science of the time was funded by such institutions.

“Perhaps one of GSSI’s greatest successes,” Cohen wrote, “was to undermine the idea that the body has a perfectly good homeostatic mechanism for detecting and responding to dehydration—thirst.”

While recommendations from bodies like the ACSM and claims from sports beverage manufacturers have been dialed back in recent years, a legacy of confusion remains. Dr. Chrystal Wittcopp is the director of the pediatric weight management program at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield. She says that both kids and parents often misunderstand the role that sports drinks play.

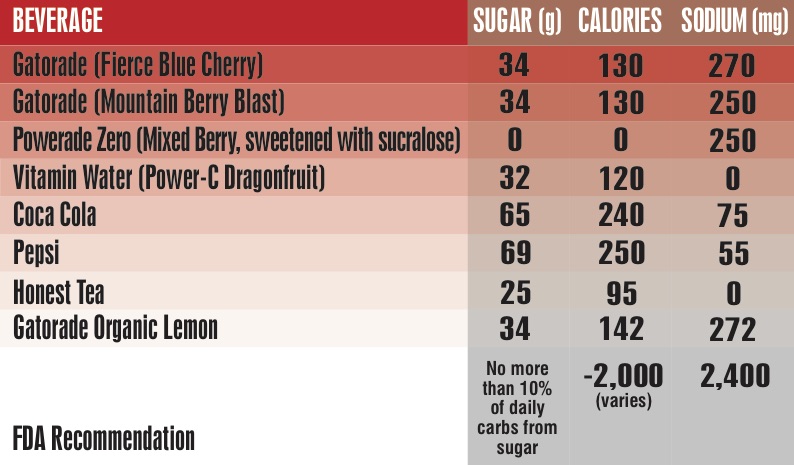

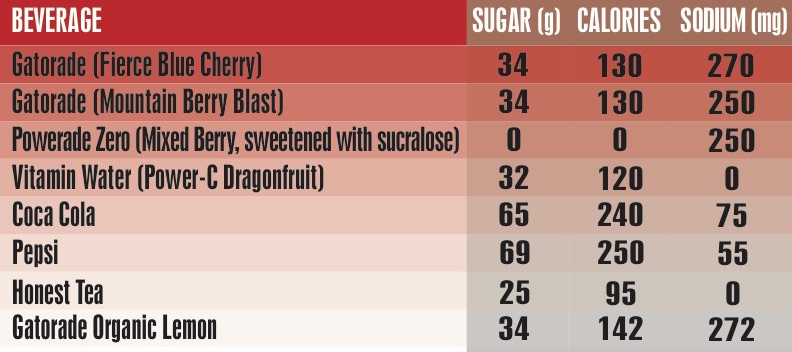

“We see a lot of children who drink a lot of sports drinks thinking that they’re a healthy alternative [to soda],” says Wittcopp. “Children are very good at buying into advertising, which advertisers know, so they fall hook line and sinker for the advertising and don’t really realize that most of the sports drinks are mainly sucrose or glucose or a high fructose corn syrup additive that sometimes are equal to what you’d be drinking in a soda or straight juice product.”

Wittcopp worries about the impact that sugary sports drinks are having on childhood obesity rates and says that there’s not much of a place for sports drinks in a child’s diet. She’s reluctant to recommend sports drinks to a child at all, she says, unless that child is performing more than 90 minutes of strenuous exercise in the heat.

“They also could just eat a banana and drink some water,” she says.

Contact Peter Vancini at pvancini@valleyadvocate.com.