If you’re like me, you studied William Cullen Bryant’s poem “Thanatopsis” in high school English class, and haven’t given it or its 19th-century author a thought since then. Well, I paid the man and his work a return visit the other day at his hillside homestead, courtesy of Enchanted Circle Theater. It was an eye- and ear-opening experience that was worth the wait. A Fiery and Still Voice is a brief, peripatetic two-character play performed at the Bryant Homestead in Cummington, Mass., a scenic half-hour drive from Northampton – an ideal autumn outing.

Enchanted Circle, the Holyoke-based educational theater, is so good at this kind of site‐based “living history,” going the Old Sturbridge Village and Plymoth Plantation–style historical recreations one better. In previous productions like The Skinner Servants’ Tour, a visit with the household of one of Holyoke’s mill moguls, the performers inhabit the very rooms still ghosted by their subjects, and in this one the author’s own words, drawn from his meditative poems and a lifetime of correspondence, fill the air he breathed.

Enchanted Circle, the Holyoke-based educational theater, is so good at this kind of site‐based “living history,” going the Old Sturbridge Village and Plymoth Plantation–style historical recreations one better. In previous productions like The Skinner Servants’ Tour, a visit with the household of one of Holyoke’s mill moguls, the performers inhabit the very rooms still ghosted by their subjects, and in this one the author’s own words, drawn from his meditative poems and a lifetime of correspondence, fill the air he breathed.

If Bryant is remembered at all today, it’s as a poet whose “still voice” has long since dropped out of the curriculum. But as I learned from this play, in his own time he was known more as a fiery abolitionist, crusading journalist, political activist and campaigner for conservation and civic improvement. He was the first advocate for the creation of New York’s Central Park (Bryant Park, at the New York Public Library, honors his service to the city) and the first to bring a young Illinois lawyer named Lincoln to national attention.

A Fiery and Still Voice, written by Priscilla Kane Hellweg, Rachel Kuhn and Steven Angel, was commissioned from Enchanted Circle by the Trustees of Reservations, the statewide non-profit that operates the Bryant Homestead, as a way to draw more visitors and create a more vivid “tour” of the house and grounds.

Gathering on the porch that wraps around one corner of the sprawling Victorian “cottage,” we’re greeted by a lively young docent, played by Enchanted Circle veteran Melissa Redwin. She takes us back 150 years, to the fall of 1866. Frances, Bryant’s wife of nearly a half-century, has recently died, just before they were due to retire from the lively bustle of New York to the solitude of their Berkshire retreat. Now he’s here alone, aged 72, still reeling from her death but continuing to work on his series of Letters of a Traveler and persistently revising the poem for which he will be most remembered.

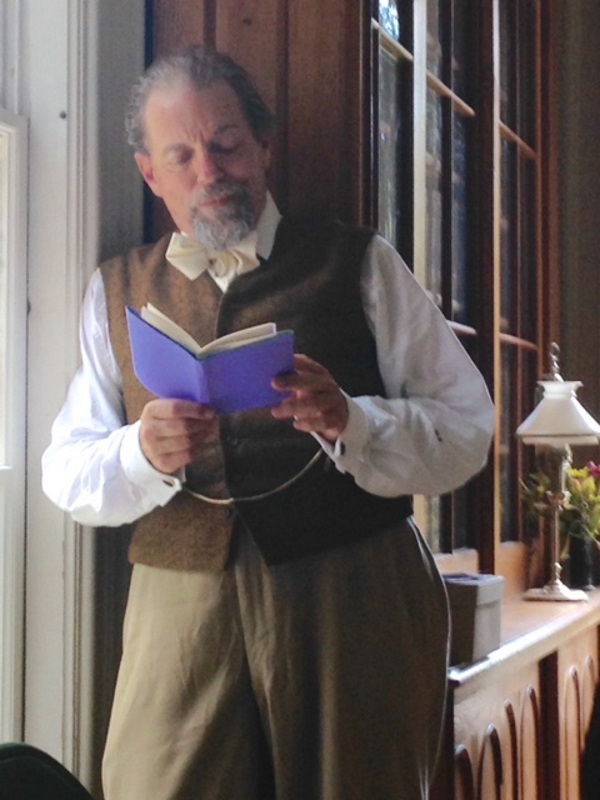

As the docent speaks, around the corner of the house strolls a living antique, a 19th-century gent in top hat and frock coat, musing and muttering to himself as he tinkers with the wording of the opening lines of “Thanatopsis,” a paean to the spirit of Nature:

As the docent speaks, around the corner of the house strolls a living antique, a 19th-century gent in top hat and frock coat, musing and muttering to himself as he tinkers with the wording of the opening lines of “Thanatopsis,” a paean to the spirit of Nature:

She has a voice of … – What? A voice of joy? pure joy? No – gladness.

She has a voice of gladness and a smile

And eloquence of beauty.

Court Dorsey plays Bryant, and while his beard is less luxuriant than his model’s (in later life Bryant’s whiskers, if not his verse, rivaled those of his contemporaries Whitman and Longfellow), he creates a rich portrait of the man’s restless intelligence, eccentric nature and deep feeling for family, nature and nation.

We follow him into the house, where we cluster along the walls of the dining room, unseen eavesdroppers on his solitary breakfast of brown bread and milk, in accordance with his devotion to simple living and homeopathic principles. From there to his study, where he sorts through piles of letters and documents – “Lincoln. Lincoln. Evening Post. The Orient. Turkey. Olmsted. Naples. Tinctures. Central Park. Lincoln.” – and recalls his own criticism of the president’s Emancipation Proclamation, which Bryant considered a timid half-measure: “Gradual emancipation! There is no grosser delusion ever entertained by man.”

We follow him into the house, where we cluster along the walls of the dining room, unseen eavesdroppers on his solitary breakfast of brown bread and milk, in accordance with his devotion to simple living and homeopathic principles. From there to his study, where he sorts through piles of letters and documents – “Lincoln. Lincoln. Evening Post. The Orient. Turkey. Olmsted. Naples. Tinctures. Central Park. Lincoln.” – and recalls his own criticism of the president’s Emancipation Proclamation, which Bryant considered a timid half-measure: “Gradual emancipation! There is no grosser delusion ever entertained by man.”

Finally, we find Bryant outdoors, seated under a spreading maple overlooking the spacious meadow that rolls down toward the old-growth forest memorialized in his poem “The Rivulet,” recalling his lifelong companion: “I never wrote a poem that I did not repeat to her, and take her judgement upon it. She loved my verses, and judged them kindly, but did not like them all equally well.”

Photos by Priscilla Kane Hellweg

If you’d like to be notified of future posts, email StageStruck@crocker.com