The debate over immigration reform isn’t new, but it’s taken center stage in the 2016 presidential campaign. Republican candidate Donald Trump has made it a central part of his campaign and recently made headlines when he vowed to cut funding to so-called “sanctuary cities” — jurisdictions that refuse to cooperate with federal requests for help in detaining and deporting undocumented immigrants.

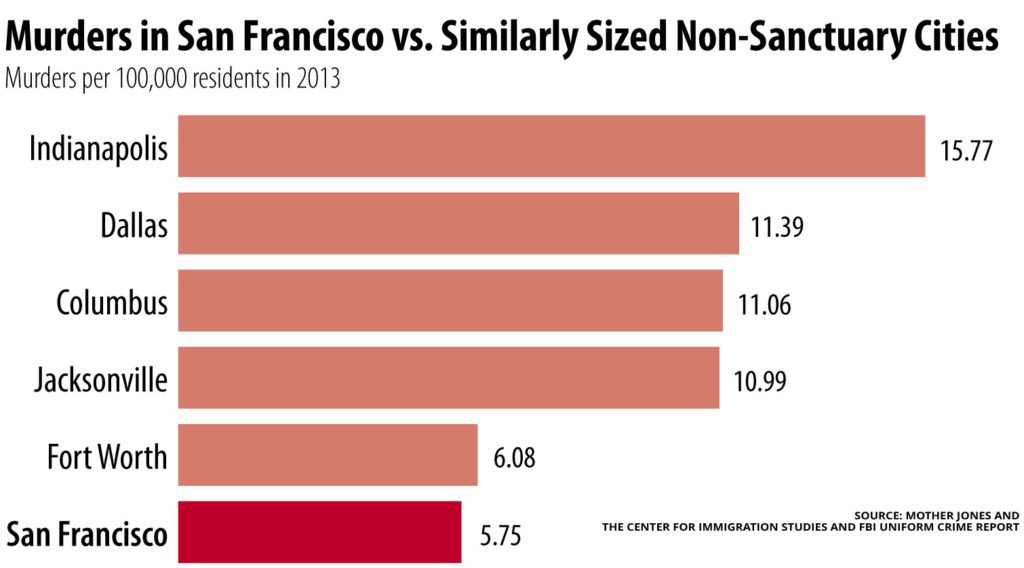

According to Trump, sanctuary cities are havens for dangerous criminals. He cited the killing of a 32-year-old woman in San Francisco — which adopted its sanctuary ordinance in 1989 — by an undocumented immigrant who had been deported five times. (It’s a terrifying story, but data shows native-born people are more likely to be criminals than those born outside of the country: 1.6 percent of immigrant males age 18-39 are incarcerated, compared to 3.3 percent of those who are native-born, according to a 2015 report by the American Immigration Council, a D.C.-based pro-immigrant think tank.)

The discussion has left many wondering exactly what sanctuary cities are and what the impact of becoming such a city might have on those within the community.

Sanctuary cities are not all the same. They offer protections that range from lip service to denying requests by Immigration Customs Enforcement (ICE). What’s more, not every police force interprets “sanctuary” the same way.

For the most part, sanctuary cities are characterized by police departments that deny requests — known as detainers — by ICE officials to delay the release of an undocumented immigrant up to 48 additional hours so that they can be taken into federal custody. There is no federal mandate for local law enforcement agencies to comply with ICE detainer requests, and many — through executive action, legislation, or unilateral action by police departments — choose not to.

A detainer request comes when ICE asks a local police department to hold a person for up to 48 hours — enough time for federal agents to take the person into custody. When a person is arrested, police check for outstanding warrants and whether or not that person has any prior convictions. In addition, the arrested person’s fingerprints are automatically cross-checked against a series of federal databases using an electronic system, including an ICE database of known immigrants and deportees. If the person is in the database, ICE receives an alert. According to Neudauer, such an alert would “indicate an immigration encounter at some point in the past, either positive or negative.”

Locally, western Massachusetts is home to at least two sanctuary communities — Northampton and Amherst — which have passed resolutions containing language directing police departments not to honor federal Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) detainer requests to whatever extent possible.

Additionally, Holyoke Mayor Alex Morse issued an executive order in 2014 directing police not to comply with civil immigration detainer requests, in line with existing police practice in the city, though the city council has not passed a resolution.

Yet, even in communities that consider themselves “sanctuaries,” undocumented immigrants get detained and deported.

In August of this year, the deportation of Jose Alfredo Ramirez Arias, an undocumented El Salvadoran immigrant who was working and residing in Amherst, left some confused about whether Amherst was cooperating with federal immigration officials. Prior to being deported, he was detained in Greenfield for a month, according to a Gazette report earlier this year.

Ramirez Arias was on ICE’s radar due to a Sept. 11, 2012 arrest by Northampton State Police on the charge of operating a motor vehicle under the influence of alcohol, according to ICE. This offense made Ramirez Arias a “Priority 2” undocumented immigrant for ICE, which means he was wanted for being a “recent illegal entrant,” according to an ICE priorities director’s memo explaining the program.

He was placed in “removal proceedings” after being convicted for drunken driving in 2012.

Ramirez Arias, a 38-year-old father of four, had worked as a chef at Bistro 63 and the Monkey Bar in Amherst since fleeing violence in El Salvador. Following his detainment in Greenfield, Ramirez Arias received support from his employer and community members who railed against his deportation, writing letters of support and declaring him an upstanding member of the community.

“We really didn’t have anything to do with that case,” says Amherst Police Chief Scott Livingstone. “I learned about that when I read it in the paper myself … It’s a sad situation.”

Livingstone says it is not his job to make a judgement about whether the decision to deport Ramirez Arias was the right move.

“I don’t think it’s the responsibility of the local law enforcement authorities to be doing the jobs of the federal government,” Livingstone says.

But that doesn’t mean there aren’t instances when detainment makes sense.

The Ramirez Arias incident “would be a perfect example of taking things on a case-by-case basis,” Livingstone says, but added later, “I am, as you know, sworn by law to uphold all of the laws, local, state, and federal.”

The Valley isn’t the only place with a few sanctuaries. States — including Connecticut — counties and cities across the U.S. have adopted similar policies limiting the cooperation of local law enforcement with federal Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

Locally, ICE detainer requests are fairly uncommon. Northampton Police Chief Jody Kasper estimates her department has received two or three ICE detainer requests in the last five years. Amherst Police Chief Scott Livingstone says that he can’t recall Amherst ever having received one. But according to local law enforcement, knowing where a community stands on the issue is important to building trust with the community and protecting the safety of undocumented residents who could become easy targets and unwilling to come forward because of their immigration status.

“It’s certainly something we need to think about because my officers are out there every day,” Livingstone says. “They’re all our citizens and it’s our responsibility to have trusting relationships with these people, so yeah, we need to consider that.”

It’s important to note that there is no legal definition of the term “sanctuary city” because they are not officially recognized by the federal government while legislation at the local and state levels varies.

“Hopefully what it means is that any of our citizens who are undocumented who are victims of or witnesses to crimes feel more comfortable coming forward and participating in the criminal justice system without fear of having a federal response and having them removed from our community,” says Kasper, Northampton’s police chief.

“That’s really the impetus behind this whole concept is that we don’t want people in our community who are easy victims for anybody because people would know that they wouldn’t feel comfortable coming forward.”

And how does ICE feel about sanctuary cities?

“I mean, we understand that they exist or that the term kind of describes a certain series of events or maybe judicial or even an ordinance that local communities put in place,” says ICE spokesperson Shawn Neudauer. “But that’s not really for us to comment on.”

In Northampton, the city council voted in 2011 to adopt a resolution not to comply with ICE detainer requests. It was reinforced in 2014 by an executive order by Mayor David Narkewicz, which ordered police not to comply if the request pertained to a non-criminal investigation or was not subject to a warrant.

In May of 2012, Amherst passed a resolution at the Annual Town Meeting which declared that the town would refuse to cooperate with federal investigations of undocumented residents to the extent possible. The policy was originally written as a bylaw, which would have mandated that the town decline to cooperate with ICE, but was recast as a resolution amid concerns that it would jeopardize use of federal grants that the town receives for alcohol enforcement, speeding enforcement, and bicycle safety, the Gazette reported at the time.

Police Chief Scott Livingstone was one of those advocating for the non-binding resolution instead of the bylaw, saying he would prefer to decide whether to comply on a “case-by-case” basis should an ICE detainer request be received.

“That’s the direction and the memorandum that we sent out to our officers is that it needs to be taken on a case-by-case basis,” Livingstone says. “We have protocols in place where the captain of operations is immediately notified and then I’m notified and that would become my decision.”

Contact Peter Vancini at pvancini@valleyadvocate.com.