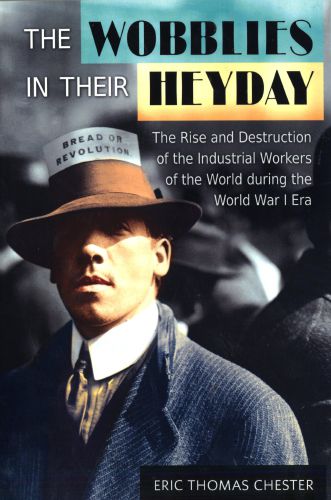

The Wobblies in Their Heyday: The Rise and Destruction of the Indistrial Workers of the World During the WWI Era, by Eric Thomas Chester

Levellers Press, levellerspress.com

In the early 20th century, when unions in the United States were fighting pitched battles with factory owners and industrial barons for better pay and working conditions, perhaps no labor organization had greater clout and visibility during WWI than the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW).

But the IWW’s success at leading strikes against key industries prompted the U.S. government to crush the union during World War I, sending many of its leaders to jail.

In The Wobblies in Their Heyday, Eric Thomas Chester, a former professor of economics at the University of Massachusetts Boston, revisits that story, tracing the union’s rise from the mining pits of the U.S. West to its destruction at the hands of the administration of President Woodrow Wilson.

In The Wobblies, published by Levellers Press of Amherst — Wobblies was the nickname given to IWW members — Chester makes the case that the IWW was “a unique phenomenon,” with 150,000 members who had relatively little education and skills but were committed to fundamental social change — giving working people decent lives and erasing the rampant economic inequities produced by capitalism.

Among the group’s members were some of the most famous labor leaders from the era, including “Big Bill” Haywood, who became an inspirational figure in Massachusetts when he helped run a prolonged but successful strike at a Lawrence textile mill in the winter of 1912-13 — the famous “Bread and Roses” strike.

Chester’s book offers portraits of Haywood and other IWW leaders, who regularly faced violence for their organizing efforts at sites like the huge copper mines in Butte, Montana. U.S. soldiers, company thugs and local law enforcement attacked and jailed IWW leaders and members; one union leader, Frank Little, was beaten and then lynched by vigilantes in Butte in 1917.

But it wasn’t until WWI that the full wrath of the U.S. government came down on the IWW. The union opposed U.S. participation in the war, considering it a fight between capitalists in which working men were expected to do the killing and dying.

When IWW-led strikes slowed production of resources such as copper and timber needed for the war effort, U.S. Department of Justice agents raided IWW offices across the country, seizing reams of documents and arresting hundreds of union members.

Eventually, 101 IWW leaders were convicted and jailed on charges such as conspiring to hinder the draft and other alleged crimes against the war effort. The union was effectively labeled a militant force and largely destroyed, Chester notes, though it has continued in a smaller form for years.

It didn’t have to be that way, he writes. Wilson could have resolved disputes at industrial sites by calling for decent working conditions and wages for IWW and other union workers, especially when many companies were realizing record profits during the war.

But “the president’s refusal to confront powerful corporations, and instead side with them against the workers, is indicative of the extent to which he, and the Democratic Party he represented, was subservient to the corporate establishment.”

Finding Wonders: Three Girls Who Changed Science, by Jeannine Atkins

Atheneum Books For Young Readers, jeannineatkins.com

Whately author Jeannine Atkins has penned a number of books for younger readers on girls and young women who bucked gender stereotypes in the past to become naturalists, scientists and experts in other fields typically dominated by men.

A poet and essayist as well as a prose writer, Atkins has returned with a new book that explores similar ground while also using an unusual format. In Finding Wonders, she profiles three early women scientists, and she tells their stories in prose poems.

Maria Sibylla Merian, born in Germany in 1647, became a naturalist and scientific illustrator at a time when not only did women not do such things but “few [people] dared to use science, instead of superstition, to explain natural events.”

Merian would eventually defy convention further by sailing to South America with her daughter to sketch new-world insects in Suriname, then a Dutch colony.

Atkins also writes of Mary Anning, a 19th-century English paleontologist who made important discoveries about Jurassic-era fossils, and Maria Mitchell, a 19th-century American astronomer. Among her accomplishments, Mitchell taught astronomy at Vassar College for 20 years, defying a request from a male dean to use her telescope to spy on students trying to leave the grounds of the all-women college.

“She’s an astronomer, not a warden or judge,” Atkins writes. “She tells her students to be curious, to do their best,/ and to ignore small rules, such as those about lights-out./ They must break curfew and join her for work that begins / after dark.”

Contact Steve Pfarrer at spfarrer@gazettenet.com.