It was an intense meeting in the winter of 2015: On one side of the room sat the owners and operators of the Mt. Tom Generating Plant, a coal-fired power station on Route 5 in Holyoke. On the other were 60 community members and environmental activists.

Carlos Rodriguez, a 59-year-old retired factory worker, was among the activists. Rodriguez, of Holyoke, had the words of his family and friends ringing in his ears — “They’ve got the money,” “You’re wasting your time” — when he stood up to say his piece at one of two community planning meetings to decide what would happen to the plant since it had ceased power production in 2014.

The cheap price of gas, a steady shift away from coal in the nation’s energy plans, and years of anti-coal advocacy had conspired to shut the coal plant down in 2014. Rodriguez, like many people in the community, wanted a solar power plant to be built on the grounds of the coal plant, but GDF Suez (now Engie), the plant’s owners, weren’t convinced yet.

“At one point in the meeting, they said they’d like to do solar — if it’s economical,” said Lena Entin said during a celebration of the solar plant’s groundbreaking held last month at Fiesta Cafe in Holyoke.

“And I said, ‘What do you care more about profits or people?’” Rodriguez said.

“And then he just let it hang there, it was silent,” recalled Entin, development director with the grassroots advocacy group Neighbor to Neighbor. “He just let the weight of those words sit there.”

Rosa Gonzales and Carlos Rodriguez, members of Neighbor to Neighbor at Fiesta Cafe during the celebration of the Solar Farm in Holyoke

Rodriguez said he got involved with Neighbor to Neighbor in 2003 and became active in the community group’s work to shut down the coal plant in 2010 because of the high rate of asthma in the city. Rodriguez’s wife, Rosa, also has asthma.

More than a quarter of Holyoke school students — 28 percent — have asthma, according to the Massachusetts Department for Public Health. For a comparison, the asthma rate among Springfield school students is 18.6 percent. Research conducted on the relationship between coal ash and asthma is scarce, but that’s starting to change. In 2012, a University of Louisville studied the link between human health and coal ash exposure. University epidemiologist Kristina Zierold compared a neighborhood of 231 adults and children that is exposed to nearby coal ash repositories and 170 people from a neighborhood where coal ash is not present. Of the two groups the one with exposure to coal ash had higher rates of illnesses such as asthma, emphysema, and cancer.

“The coal plant has been going for 50 to 40 years in a row and only Holyoke has the asthma like this,” Rodriguez said. “We went to [GDF Suez] with facts. You can’t just say, ‘I want you to shut this down because it’s bad.’ How do you know it’s bad? You’ve got to have the numbers to prove it.”

With a $100,000 grant from the state, Holyoke worked with Massachusetts Clean Energy Center to conduct a reuse study. The top suggested reuse for the largely restricted land — due to the nearby wetlands, river, endangered animals, and toxins — was a “farm” planted with panels to generate electricity from sunlight.

“We were trying to determine what to put on that site when Mass Clean Energy Center came out with their study,” said Carol Churchill, communications manager at Engie North America. “The land was very conducive to a solar facility … and [Holyoke] was looking for non-carbon sources.

“Everything pointed to solar, so that’s what we ended up installing.”

Hailed as one of the largest in the state, the 5.76 megawatt solar plant being installed at the old coal plant along Route 5 in Holyoke is considered a big win for environmental and community activists.

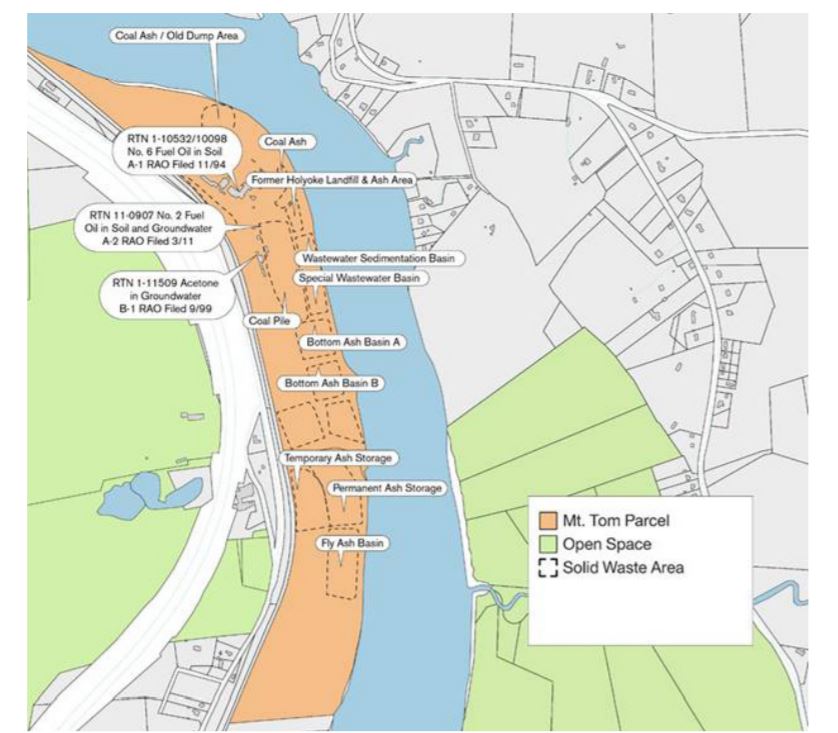

But their battle with coal isn’t over. Toxic waste created during decades of coal-fired energy production led to the creation of 21 ash ponds and two dumps on the 128-acre, Connecticut River-adjacent property. There’s also the issue of energy supply. Though reliance on the Mt. Tom coal plant had significantly diminished over the years — when it shut down, the plant was only running during peak demand times in the winter — the plant was built with a 146 megawatt-production capacity.

Rosa Gonzales and Carlos Rodriguez, Lena Entin, Jane Andresen, Aaron Vega and Claire B.W. Miller make a toast during the celebration of the Solar Farm in Holyoke

Claire Miller, state director of the Toxics Action Center, said she is worried the creation of a solar plant will lull people into a false sense of environmental security.

“We’re concerned that this is it, we got solar — and oh, yay, that’s great. But if you look into this, it’s still a process,” Miller said. “The DEP is still in process to determine the outcome of the clean up.”

Miller said because the Mt. Tom plant is in the midst of a floodplain right next to the Connecticut River and above a potential drinking water aquifer, cleanup could be dangerous. But so, too, could leaving the ash there to potentially leach into the ground.

Claire B.W Miller talks about the Holyoke Solar farm during a celebration at Fiesta Cafe.

Engie representatives have said the company is committed to making the area safe for people and the environment. Churchill said the company would like to begin demolition of the plant’s smoke stack and main building in 2017, but that plan — which would need to be submitted to the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) for approval — is still being formed.

“Some of the small structures might be taken down before the main structure,” Churchill said. “It takes some engineering work and there’s some asbestos we have to get rid of and things like that. We have to determine which method is best suited for the demolishing. It’s a pretty big undertaking.”

Coal plants are notorious for polluting the air with particulate matter. Small particles that carry on the breeze and obstruct people’s ability to breath, as well as lots of ash, which contains heavy metals such as arsenic, lead, selenium, and other cancer-causing agents. In response to a billion-gallon ash spill in Tennessee in 2010, and a growing public concern over the disposal of coal ash, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) enacted new regulations in October for the disposal of coal combustion residuals from electric utilities.

The rules require any existing unlined coal ash dump that is contaminating groundwater or found to be structurally unfit to either remedy those problems or close. Enforcement of the rule is left to states; the EPA doesn’t have the authority to enforce the new regulation. In its decision, the EPA stopped short of declaring coal ash a hazardous material.

When a coal plant closes, it is still subject to some state and federal regulations. But because it no longer operates, reports to government watchdogs are not required, Miller said. This means the ash and old soil is left in the ground, which leads activists to worry about the potential for toxins to leach into the surrounding earth and water. Because monitoring is not required, no one is likely to discover the pollution right away.

“We need state legislators to be on this,” said Emily Norton, Massachusetts chapter director of the Sierra Club. “There’s all this talk about meeting utilities in the middle when it comes to the environment, but the Earth can’t meet in the middle. We need to do what environmental scientists say we need to do.”

At the Mt. Tom site, ash fill stashes are mostly unlined, according to an analysis of EPA records by Earthjustice, an environmental conservation nonprofit. The areas are, however covered by soil and vegetation, the Massachusetts Clean Energy Center study found. In 2006, the state Department of Environmental Protection developed a draft plan to close the ash fill areas, but that was dropped when the environmental agency couldn’t come to terms with the Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program about how to proceed, according to the Clean Energy Center study. The area is home to endangered eagles, dragonflies, and mussels.

The solar plant is being built on 22 of the company’s “virgin” acres that were formerly used as farmland.

State Rep. Aaron Vega (D-Holyoke) said he is unsure of what oversight state lawmakers can provide as work goes on at the old coal-fired plant.

“We have heard from the company, though, that they want to take care of this and they want to take the entire building down,” Vega said. “Massachusetts regulations will be enforced.”

In Massachusetts, coal ash is exempt from hazardous waste regulations. It’s also exempt from solid waste regulations as long as the material is being repurposed into fill, concrete, road block or some other beneficial item. The only way the Department of Environmental Protection can get involved with the coal ash deposits at Mt. Tom are if the department decides the ash fill has created a nuisance condition due to odor, dust, fires, smoke, or other conditions, or if Engie decides to voluntarily remove the waste — a move that could disturb the soil and release ash.

Ground was broken on the 5.76 megawatt solar plant on the Mt. Tom plant site late last month and Engie expects to be producing energy during the first three months of 2017. Though it won’t come close to the 146 megawatts coal plant was built to produce, the city is able to weather this drop in electricity production from Mt. Tom because Holyoke Gas and Electric has been increasing its sustainable energy portfolio for years, said James Lavelle, HG&E’s manager.

Most significantly, the municipal energy provider purchased the Holyoke Dam/Canal System in 2001. Two-thirds of Holyoke’s energy needs are met with hydropower, Lavelle said. Once the Mt. Tom solar plant is on-line, and a couple other smaller solar plants start producing power in early 2017, 75 percent of Holyoke’s energy will be derived from renewable resources and 98 percent of the energy will be carbon-free, Lavalle said.

“It’s fair to say renewable resources are the only investments that could possibly be considered likely candidates for this site,” said Lavalle. The Mt. Tom solar plant “helps us make good strides toward that goal of a smaller carbon footprint.”

Miller, the Toxics Action Center organizer, said she’s excited about Holyoke’s clean energy future, but it doesn’t undo past pollution. Without advocates keeping up the pressure on coal ash, she said, the Pioneer Valley could find themselves in the same place as North Carolina. Back in 2014, a Duke Energy plant near Edin, North Carolina leaked 39,000 tons of coal ash and 27 million gallons of ash slurry into the Dan River, polluting it for 70 miles. The company, which saw more than $23 billion in revenue last year, received about $100 million worth of fines for allowing coal ash from the closed plant to contaminate the water.

“The Mt. Tom plant is old and the coal ash there is extremely toxic,” Miller said. “It’s in a floodplain and my understanding is it’s just a matter of time before the waters reach it — and then what happens?”

Kristin Palpini can be contacted at editor@valleyadvocate.com.