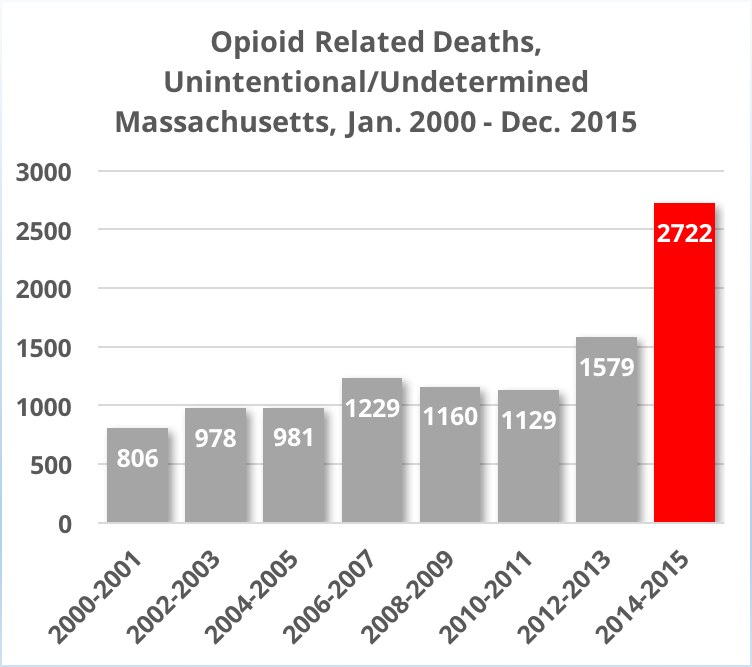

Between 2013 and 2015, the number of opioid-related deaths state- wide surged from 918 to 1,578 — an increase of over 70 percent in two years.

The opioid crisis in Massachusetts has reached epidemic proportions, according to the findings of a report out this past September from the Massachusetts Department of Public Health. Opioids are a class of addictive painkiller that includes common drugs like morphine, codeine, heroin, oxycodone, and fentanyl. In 2014, the rate of fatal overdoses in Massachusetts reached more than twice the national average for the first time in 15 years — increasing at a rate unprecedented for the Bay State.

The study, called the Chapter 55 Report after the emergency legislative mandate that created it in August of 2015, is touted by researchers as a “deep dive” through 10 different datasets from five state agencies. The root causes of the opioid epidemic are multifaceted, the report says, but no single substance or factor is solely responsible.

Still, a major contributing factor seems to be the rise of fentanyl, a legally prescribed pain- killer that has found its way into heroin supplies across the country. The problem is particularly bad in Massachusetts, according to the Centers for Disease Control. In 2015, over 60 percent of toxicology samples in the state tested positive for fentanyl, up from 40 percent in 2014. It’s also begun appearing in post-mortem toxicology reports without the presence of other drugs. The DEA says that the drug is being illegally manufactured in lethal potencies often 50 times greater than that of heroin.

Starting in 2015, the findings show a decrease in heroin deaths, but a proportional spike in fentanyl deaths, yet the percentage of patients in treatment listing heroin as their primary substance of use has spiked dramatically over the same time period. Many heroin users may not realize that they’re actually using fentanyl.

The report also found that those who OD are far more likely to die of an illegally obtained substance than a prescribed one. Two-thirds of those who died of an opioid overdose in 2013 and 2014 had been prescribed opioids since 2011, but only one in 12 had an active prescription in the month before they OD’ed.

Gov. Charlie Baker signed a bill last March which limits first-time opioid prescriptions to a seven-day supply and includes provisions for educating students and doctors on the prevention and management of prescription drug abuse. The state also deployed a new database system last August to track active opioid prescriptions which now has more than 24,000 searches per day. But in an editorial this month, the Boston Globe reported that the Baker Administration is preparing to cut more than $1.9 million from the Bureau of Substance Abuse Services budget.

Here are a couple more of the report’s key findings:

- People who have survived an overdose and receive opioid agonist treatments — like methadone and buprenorphine — are significantly less likely to die of another overdose. The report recommends: The state should make these treatment options more widely available.

- Women are more likely than men to “doctor shop” and receive opioids from three or more prescribers. The report recommends: Educate prescribers on “their own personal biases” and utilize the Massachusetts Prescription Awareness Tool (MassPAT) in order to identify any active or past prescriptions for their patients.

- The risk of opioid overdose death is 56 times higher for those recently released from incarceration than for the general public, and the threat is immediate. The report recommends: Medication-assisted treatment and overdose prevention services should be expanded in correctional facilities, and access to post‐incarceration medical care and substance use prevention and treatment should be put in place prior to release.

Contact Peter Vancini at pvancini@valleyadvocate.com.