The weird and wonderful artwork of Julian Janowitz only starts to reveal itself once visitors pull onto the long driveway of his Shutesbury home. That bumpy, meandering dirt road leads through a small clearing, then along twists and turns through a tall forest of conifers. In a meadow, far off to the left, a translucent red block of glass mosaic comes into view, perched on a stone pedestal the size of a golf cart. Around the bend is a stained glass sculpture that resembles a long, white candle — or, depending on the angle, an automatic pistol. On the right: bursts of white glass stand like a series of mini explosions. And further out, along Ames Pond: a pair of dancers form a Mobius strip of sleek, joyful lines. They are electrified, like the others, and glow brightly at night.

The driveway finally curls to a stop at the edge of the pond. That’s where Julian’s house — a grand lodge, full of windows — looks out across the water and beyond, to the thick-wooded hills that mark the edge of the Quabbin Reservoir.

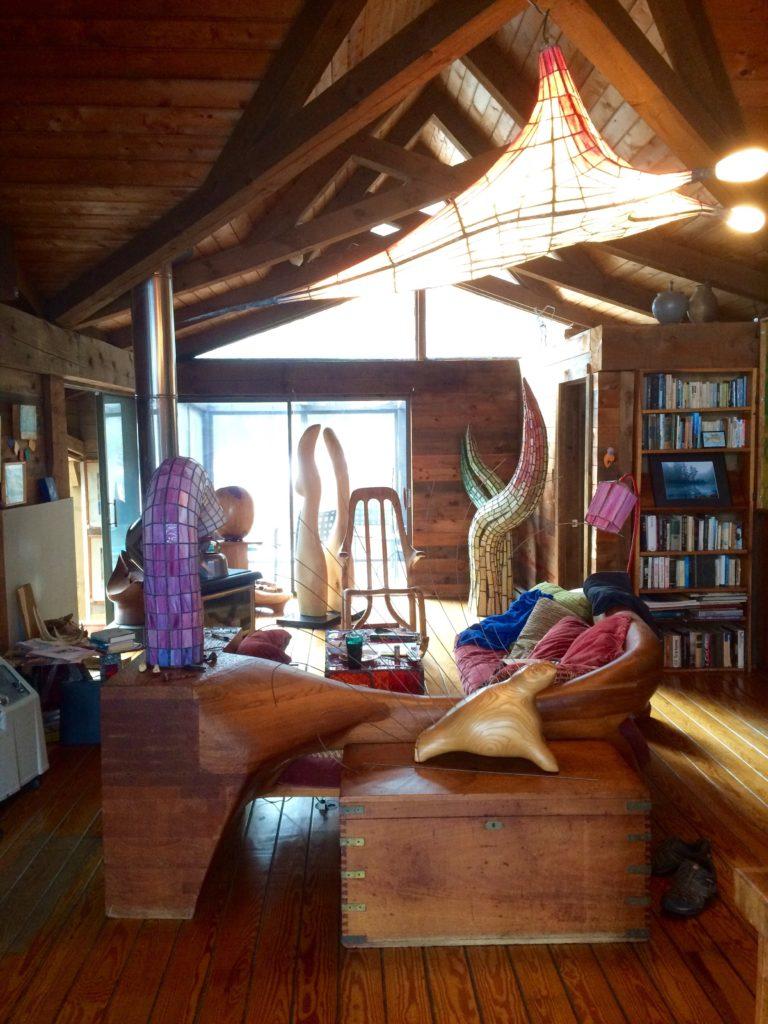

The slow-rolling journey down Julian’s driveway yields one small discovery after another, but one step into his house tells a different story. The interior is an artist’s colorful fever dream — a high-ceilinged fishbowl of a living space that brims with sculptures, paintings, toys, ornamental light fixtures, and furniture hand-crafted over the past 40 years.

It affords the retired psychiatrist time to reflect back on the decades he spent making art, all of it under-the-radar. Julian Janowitz, 87, co-founded the mental health center at UMass in the 1960s, but aside from a couple of shows years ago in Amherst and Northampton, he remains virtually unknown in the art world. Most Valley residents, including many in Shutesbury, have no idea that this 140-acre property off Wendell Road is studded with outdoor sculpture, and that the creator of all this art — who entered hospice care this past summer — must now plan for what happens next.

Hunter Styles photo

Julian bought the property in 1976, designed the house himself, and built it with his son. This place, he says, “is my soul.”

Art offered him something that a career in psychotherapy could not: physical labor. During my lunchtime visit to Shutesbury in early December, he explains to me, in between spoonfuls of lentil soup, that “I have always been sculpting and making things.”

Julian sits, propped with pillows, on the long, curved wooden couch that anchors his living room. Many years ago, he carved and polished this huge centerpiece by hand. “It was a fiery time, having a workshop here… I needed a couch, so I made this couch. I needed lights, so I made these lights. In psychotherapy, you don’t have much control,” he says. “But all of this was within my control — as much as my hands would permit. And I filled the rooms, little by little.”

“Play is intellectual, after all,” he adds. “So I played.”

Julian’s indoor collection is impressive, but when he passes, this work will likely scatter into the homes of friends, neighbors, and strangers. The house will go to his son David, 58, who lives in Austin, TX, and to his daughter Tama, 60, who lives in upstate New York. But the art installed across his property will remain in place, and those pieces — to say nothing of this beautiful land — will require protection.

That’s why he has decided to bequest the land around his house, nearly in its entirety, to the Amherst-based conservation nonprofit Kestrel Land Trust. Kestrel, which operates across 19 Pioneer Valley towns and cities, has promised to open up this private property to the public — which will require the ongoing curation and care of several outdoor sculptures and art installations.

Mark Wamsley, Kestrel’s land conservation manager, sees this “significant but bittersweet” development as a chance for the trust, in partnership with Mass Audubon, to prevent the subdivision of future house lots on this property — nicknamed “Julian’s Bower” — and to offer multi-season recreation, like hiking, skiing, and snowshoeing, along these five miles of trails.

“This is different for Kestrel,“ Mark tells me. “In the past, we haven’t focused on private properties that are maintained for public access.” This land, he says, is already protected by a conservation restriction held by the state’s Department of Conservation and Recreation, but public access — which until now has been limited to neighbors, friends, and townspeople clued in by word of mouth — is not currently ensured into the future.

Julian’s last will and testament grants Kestrel the artworks currently installed on bequest land, but the fate of his other, more portable artwork is still unclear. Mark says the land trust is likely to receive a donation of some Janowitz artwork, which would go toward a charitable auction to help establish an endowment to improve and steward the property. Still, settling the estate will likely take at least a year, and no one can be sure of the outcome just yet.

But Julian was passionate about sharing his story, Mark says, before it’s too late. “For most of his life, he didn’t want to sell his art. But he’s very proud of it.” Faced with end-stage renal failure, and a string of many quiet weeks at home, Julian was primed to discuss his legacy — and the future of this expansive wetland, nestled on the brink of wilderness.

Hunter Styles photo

It’s a strange thing, Julian tells me, “to look back on all of these years and see all of my fantasies and imaginings become three-dimensional.”

While we talk on the couch, a hoard of his sculpted wood, metal, and glass pieces stand watch from all angles. Some are bigger than Julian; other could fit in his palm. Two-dimensional art doesn’t interest him much, although he has an enormous painting on one wall called “Divorce” (he has been married twice). He made it in a hurry one day, after nailing 4×8 sheets of plywood together. It was “an expressive outburst,” he says, eyeing the rolling and crashing waves of thick, dark-hued paint. “You don’t know what the hell you’re doing or where you’re going with a piece like that — you just tap into your own amazement.”

Sculpture is different for him — more deliberate. “When you’re making something to sit in, you can’t bring quite as much emotion to it,” he says. “It has to work.” He points to a hand-carved rocking chair. “It’s an engineering process. I didn’t know about rockers, or how the curves should be. You just revise it, and revise it, until it rocks.”

Although Julian has been making art on off-hours since his teenage years, he says he was never formally trained as an art student — all of his time went toward medical school instead. His natural knack for making furniture, and abstract sculpture, almost strains credulity. But it seems, simply, to be something that he always did by himself, for himself, with no real aspirations to sell or distribute his work. “I made it for my own gratification,” he says. “That’s why I feel so connected to them. They’re all expressions of particular preoccupations I’ve had.”

The main preoccupation in his work seems to be a playful, sensual exploration of the male/female duality. Many of his sculptures are of humanoid figures, smoothed down to the simplest, intertwined gestures. This work tells stories, he explains, of “getting past the alone-ness that comes from having separate bodies.”

One piece carved from wood, which sits on a shelf in his loft bedroom, is called “The Function of the Forehead,” and it depicts two resting lovers joined in ecstasy at that special spot just above the eyes. Julian made this one just a few years ago — evidence, in a way, of the same compassion that led him to become a mental health provider. “My pull has always been toward emotional intimacy,” he says, “and exploring closeness.”

An almost childlike eagerness to harmonize with nature seems to play a large role in his art as well. He nods out the window to the statue of dancers along the edge of the pond. “It gives me amazing pleasure to construct something like that.” He made it, then — realizing that it didn’t fit in the house — drove it out to that spot on his tractor.

He also encourages me to find the magical doorway that he has installed in the woods. “When you were a kid, didn’t you ever read stories about it?” A soft smile. “I think everyone should have their own magical doorway.”

I promise to check it out. Having people on this land gives him great pleasure. I imagine it is not only his artistic eye but his age, at this point, that allows him to delight in shared perspective.

“When I look out the window and I see people walking on these trails,” he says, “I feel a kind of closeness — a sharing. There is such disharmony in the world. But here are people who chose to spend an hour walking in these woods. I find that confluence very affirming.”

I look out the windows for a long moment, then compliment him on the view. He raises his eyebrows. “Wait until you get out there.”

Hunter Styles photo

Mark meets me in the driveway, and we tramp together through leaves and fallen snow on an hour-long walk through the property. As we circle the 22-acre pond, our jackets zipped against a biting midday wind, Mark points out the little details that make these woods and bog land so special to those who have visited: the spots for ice skating, the old foundations and logging roads from this land’s former days as a sawmill, and the thousand-foot boardwalk across the marsh the Julian and his family built, long ago, by hand.

This property’s lake and pond system is also ranked among the state’s top 10 percent for biodiversity, Mark says. Moose, beaver, and other wildlife visit the pond. The wetland includes a freshwater marsh, and the bog along the pond’s shoreline contains cotton grass, wild cranberries, and unusual flora like swamp pink and round-leaved sundew.

“Ironically, this is a human-made landscape,” he says. “The pond wouldn’t be here without the dams from the old mill. Without those dams, it would be a really pretty wetland, but not nearly as rare as this is. You add Julian’s art to that — a further human embellishment on the land — and this is elevated to a really special place.”

That art is mainly sculpture, but Julian’s charming way with words sneaks into the picture as well. Along the boardwalk, he has installed a metal mailbox alongside a wooden bench. Visitors who peek into the mailbox will discover a notepad and pen for recording whatever they want, from deep thoughts to stray musings.

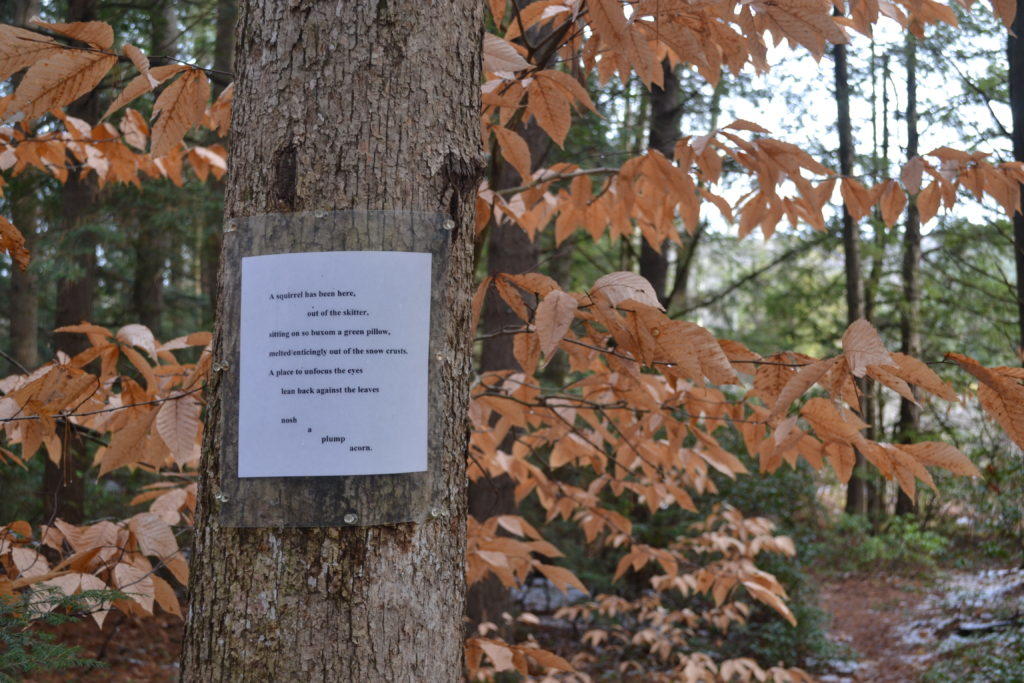

Further on, tacked to the occasional tree, are laminated poems by Julian. One reads:

A squirrel has been here,

out of the skitter,

sitting on so buxom a green pillow,

melted enticingly out of the snow crusts.

A place to unfocus the eyes

lean back against the leaves

nosh

a

plump

acorn.

Such whimsy has charmed many who have met Julian over the years, Karen Traub tells me later by phone. Karen, one of Julian’s neighbors, is an acupressurist, bellydancer, and community volunteer who is playing a lead role in organizing what she expects will become a “Friends of” group for Julian’s Bower. Kestrel plans to serve as the fiscal sponsor for the group, which will assist with trail maintenance and work to ensure continued public access to the land.

Karen first visited Julian’s land in 2005 with her six-year-old son, and she says she has come to know him well in recent years. “He’s a larger-than-life person,” she says. “His art really speaks to me, but it goes beyond that. He has vision, but he also has follow-through. He thinks it, makes it, and finishes it. Few people take all of those steps consistently.”

“We all want to have an impact on the world,” she adds, “and I think he’s made the world more beautiful with his work. I find him really inspiring.”

Karen has helped to assemble a group of about eight so far, which began meeting regularly this past summer, often in conversation with Julian on his outdoor deck. So far, she says she has had no trouble getting a “yes” from those she has asked to help with the planning. Some want to clear brush and do trail work. Others will organize and fundraise. “He has this way of drawing people to him,” she says. “This is a Friends group on the most grassroots level.”

The group has been keeping meeting agendas and minutes, but has yet to form a mission statement and a governing board. For now, most tasks are future-tense. “At this point, it’s one day at a time,” Karen says. ”We’re appreciating every day that we get with Julian.”

I am happy to hear that she has told Julian about how he has inspired her. During our interview in Shutesbury, I asked him what it feels like to rest and reflect lately, here in this house. He replied that it’s often difficult, given his limited mobility.

“Aging, and deterioration, is a very powerful sense,” he said, “when you’re here alone and waiting to die. A lot of people come through, but still I’m alone a lot of the time.”

After a moment, he smiled. “I think: yeah, it’s just about over, but it’s been a good run. For me, this represents a dream come true.”

His parents, he explained, were born in Lodz, Poland to a family of silk mill workers, and they came to America as very young children. They worked in the mills in Paterson, NJ, where Julian was born on the eve of the Great Depression.

“We lived in the ghetto,” he said. “This was always the goal: to get out of the ghetto, get educated, and find a way to live in beauty.”

And at some point over the past year, Julian said, he finally realized that he did it.

“You never know what you were about in this life,” he said, “until it’s over.”

Hunter Styles photo

Toward the end of my walk with Mark through Julian’s property, something caught his attention. On the logging road, under pine boughs soaked with melting snow, he stopped to peer down at a clod of ice on the ground. He examined it, then stood up, smiling. It was a frozen moose track, compacted and still solid in the cool shade.

“This is such a signature landscape,” he said. “A place like this has such power. I think it can even draw in people who wouldn’t normally take a walk in the woods.”

We followed the bends in the path, eventually cutting through a short stretch of woods in search of an adjoining trail. As we walked, Mark’s gaze grew serene. “Julian’s got some grandiose visions,” he said, “but this property is what it is because of his drive to achieve whatever he sees in his mind. That requires a sense of what is practical, too.”

Halfway to the next meadow, we stumbled onto just such a melding of the wondrous and the workmanlike. A small structure stood half-hidden among the pines. Its two walls met at a right angle — a corner of a room, minus the rest of the room.

Mark pushed open a bright red door in one wall, stepped though, then stopped to smack a metal gong with a hanging mallet. It went off, and the shrill echo caught in the trees.

I stepped through the portal as well. But first I stopped to read the small scrap of paper that Julian had tacked at eye level:

THIS IS THE MAGICAL DOORWAY

OF COURAGEOUS RESOLVE.

THAT VERY SAME DOORWAY

YOU HAVE ALWAYS READ ABOUT

WHEN YOU WERE A CHILD.

FIX IN YOUR MIND THE BLISS YOU SEEK

TAKE COURAGE!

STRIKE THE GONG!

GO THROUGH THE DOORWAY!

FIND THE BLISS!

OR JUST ENJOY THE LIGHT PATH.

Contact Hunter Styles at hstyles@valleyadvocate.com.