From Kuniyoshi to Cowabunga

I have to admit that it seemed odd walking through a hall of classical Greek sculptures in the George Walter Vincent Smith Museum to visit an exhibit devoted to Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles comic book art. The whole thing felt suspiciously like a ploy to get me to eat my high-culture vegetables by plying me with the sugary pop culture I craved. But I was happy to take the bait.

I’m what you might call a “pioneer millennial,” in that I was born at the distant end of the great Gen X divide. I saw this as an opportunity to reconnect with my nostalgia, and with the characters with whom I’d spent so many happy hours as a burgeoning dork. But I quickly learned that there’s nothing quite like seeing a staple of your childhood enshrined in the marble halls of a museum to make you feel the withering of age. An original Nintendo video game system is plugged into a flat-screen TV in one corner of the exhibit, clucking out the familiar eight-bit Ninja Turtles theme song that featured prominently on soundtrack to my youth. Not far away stands a 16th-century samurai suit of armor and a Kabuto helmet recognized as a Japanese national treasure.

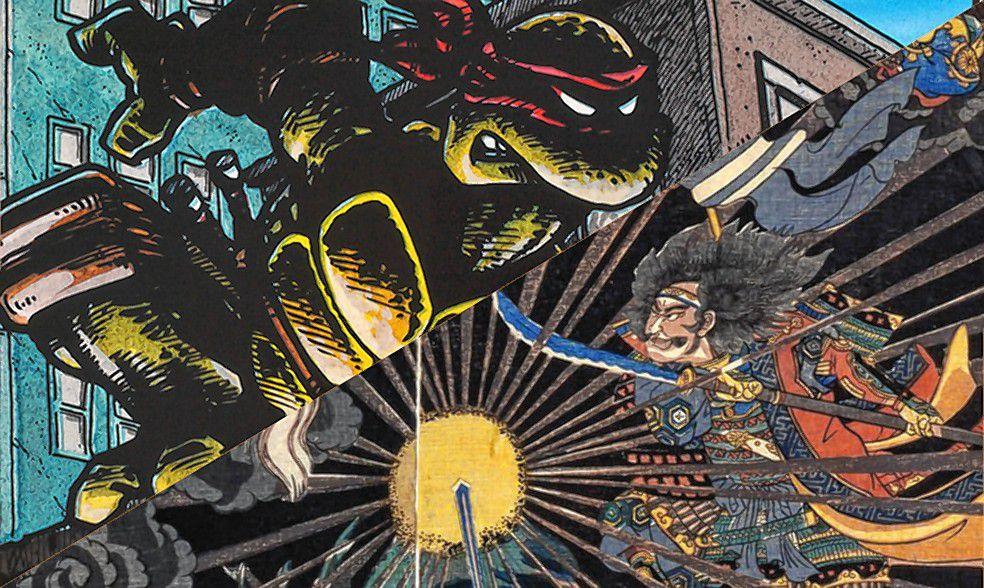

“We thought it would just be fabulous to highlight the work of the Ninja Turtle illustrators and combine it with Japanese woodblock prints of samurai warriors,” says Julia Courtney, the exhibit’s curator. “There are a lot of parallels that can be made. Then we also have a world-renowned collection of arms and armor from Japan, so we decided to put the three things together.”

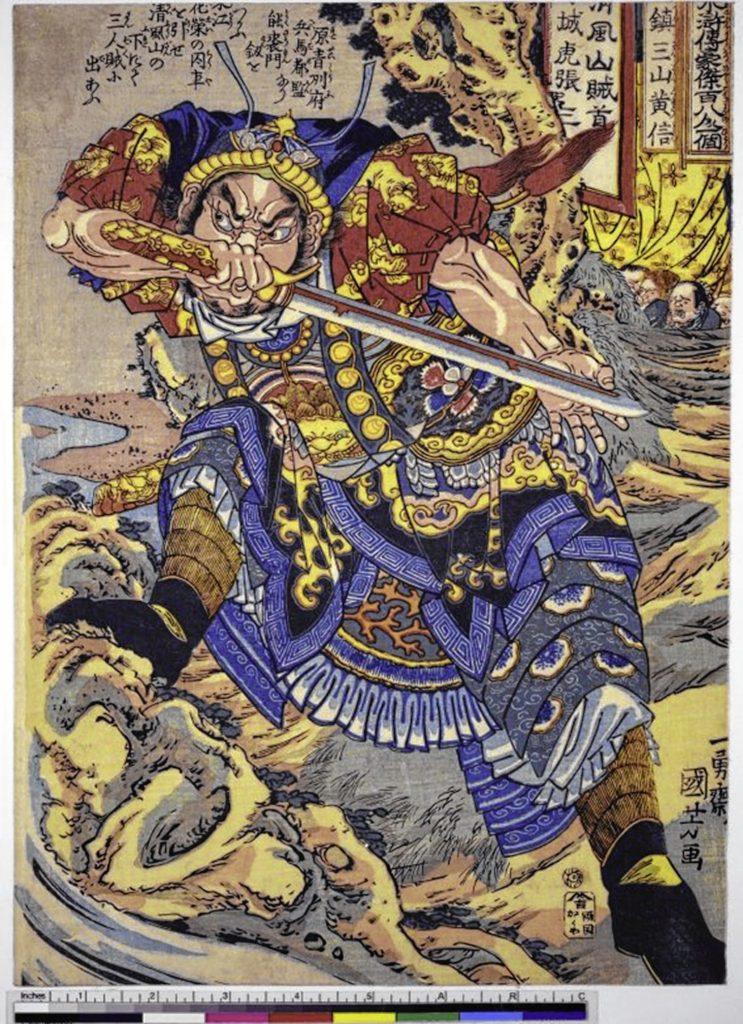

Much of the collection of Turtles artwork and memorabilia on display is on loan from Elias Derby — a private Northampton-based collector who has amassed a truly gigantic assemblage of Turtles memorabilia. This is combined with the museum’s own world-famous collection of 19th-century Japanese wood block prints and 14th- and 15th-century samurai weaponry and battle armor.

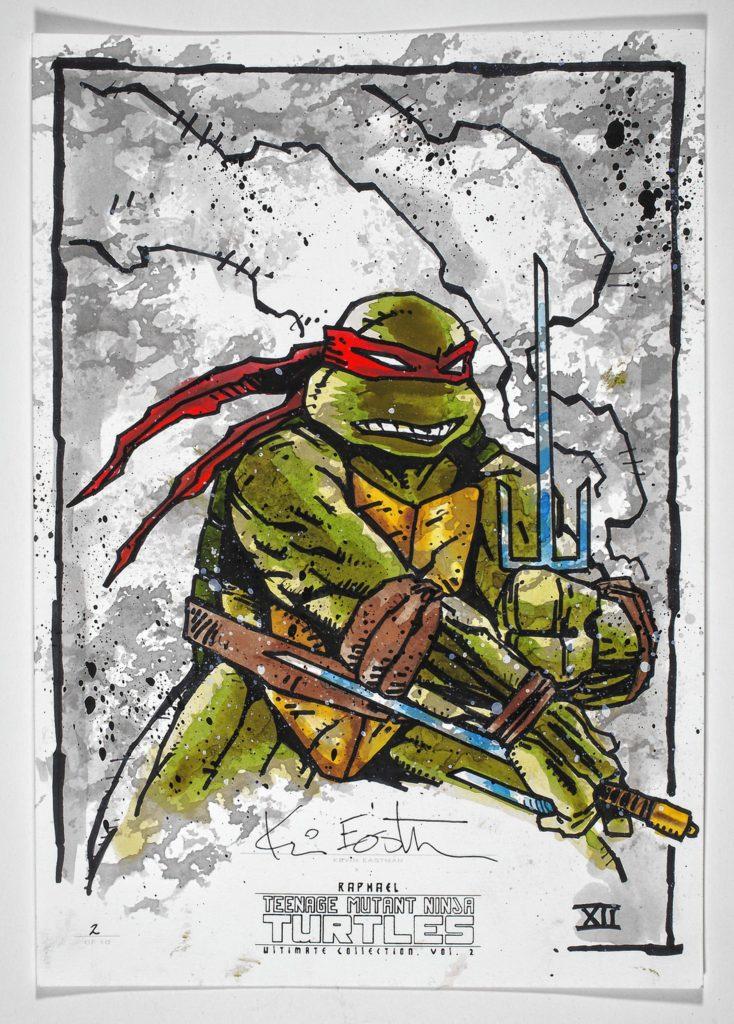

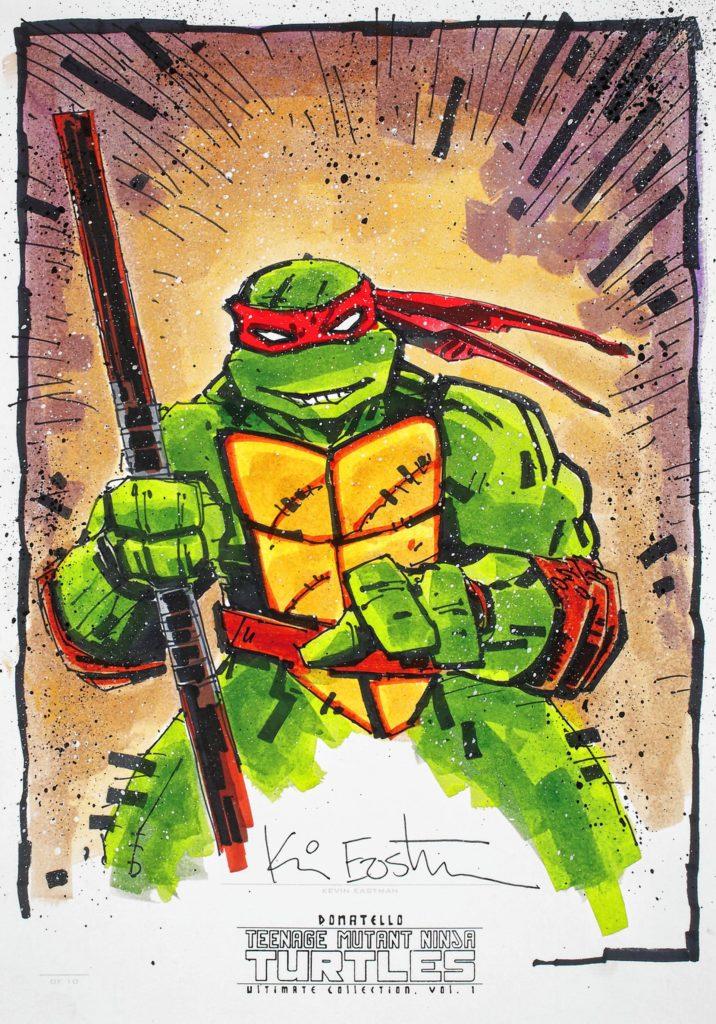

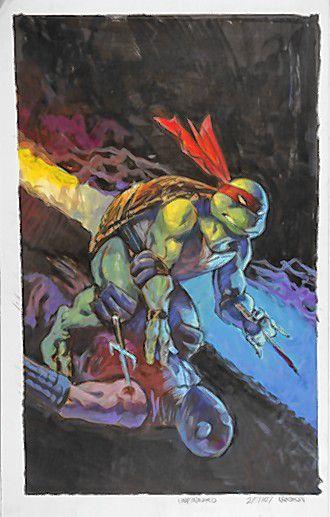

A plaque reading “Meet the Turtles” is affixed to a nearby column, adjacent to several giant portraits of the Turtles — Leonardo, Donatello, Michaelangelo, and Raphael. They’re depicted in action poses, on the verge of unleashing their wrath upon some unseen foe. The artists are Kevin Eastman and Peter Laird — their inventors.

There’s a common misconception that Eastman and Laird conceived of the Ninja Turtles while living in Northampton, but the truth is that first Ninja Turtle was drawn in Portsmouth, New Hampshire in 1983. Laird and Eastman’s company — Mirage Studios — established headquarters in Northampton in 1986, where it remained during the Turtles’ most fruitful years. In those early days, they couldn’t have predicted what a wildly successful and enduring commercial franchise it would become.

The Ninja Turtles continue to spawn movies, TV shows, and video games in the 30 years since their inception, but their most lush and varied artistic interpretations were revealed through the comics. The work of 20 Mirage illustrators adorn the museum walls, varied in medium. There are the abstract and exaggerated caricatures of Jim Lawson and the manga-inspired ink/duotone works of Eric Talbot. There are the many detailed and disturbingly realistic watercolors and ink drawings of Michael Zulli, who portrayed the Turtles through dark, detailed watercolors as beaked, reptilian-human hybrids, with muscles that look like they belong on a work by Michelangelo (the sculptor, not the turtle). Those stand in stark contrast to the pudgy-faced characters originally drawn by Laird and Eastman.

The ink drawings of Sophie Campbell are evocative of the Japanese wood block prints, in the ukiyo-e (“images of the floating world”) style, with saturated colors and earth tones. Some of Campbell’s work is even done in diptych, a nod to 19th-century artists on display.

“It’s almost like when you take an art class and everybody’s drawing a bowl of fruit, yet everybody’s piece is so different looking,” Courtney says. “That to me is one of the fun elements.”

The art seems to traverse two worlds. Portraits of warriors both pop and historic hang alongside one another in striking similarity. Like the modern sequential art, the passage of time and the telling of a story was at the heart the Japanese prints, Courtney says. She gestures to an Ando Hiroshige print in the glass case to prove her point. It’s covered with decorative Japanese characters and, to my surprise, it’s complete with thought and dialogue bubbles. That is not the only piece to share qualities with modern sequential arts. Utagawa Kuniyoshi’s vivid woodblock print Rorihakuto Chojun tells the story of a band of ethical bandits which, according to the plaque, enjoyed such great popularity that it was trendy among young men of the day to get tattoos of Kuniyoshi’s warriors.

“A lot of the Japanese prints that were created, they weren’t allowed to talk about current political climate or current leaders, so that’s why they reached back into history so far,” Courtney says. “Even though some of these were created in the 19th century as a popular ukiyo-e style print, the stories themselves actually hearken back through history.”

Scanning the walls, my eyes settle on an Utagawa Kuniyoshi print depicting about a dozen turtles. I look a little closer and am stunned to notice that these turtles have human faces.

“We just couldn’t help ourselves,” Courtney says. “[The artists] weren’t permitted to create images of kabuki actors, so you see the different faces on the turtles that have hints of who the actor was … It’s a little creepy.”

The extent to which the work of Kuniyoshi and his contemporaries inspired the work of the Ninja Turtles illustrators is up for debate, but the parallels are telling. In comparing the art, enduring themes emerge across the centuries: stories of righteous vagabonds living by a code of honor and fighting evil. It made me wonder whether the work of artists like Campbell and Zulli will adorn the walls of a museum several centuries from now.

“We hope that [kids] will look at history as something that is alive still,” Courtney says. “When you walk in and see the Ninja Turtle sculptures and the ancient weaponry, I think your brain sort of puts the two together, and a lot happens. A lot of questions arise.”

“Turtle Power! Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles & Samurai Heroes” runs through May 14 at the Springfield Museums. Contact Peter Vancini at petevancini@gmail.com.