From the outside, 5 Appleton St. in Holyoke looks like any number of towering, brick artifacts from a time when Holyoke earned its unofficial title “The Paper City.” But looks can be deceiving. New life is being breathed into the 200,000 square-foot facility and that’s all due to recreational marijuana.

Unlike some of the neighboring buildings, this 125-year-old mill, located in the downtown canal district, has been busy since starting as the Norman Paper Company in the late 1800s. As the demand for paper receded, a new business took over the building as a separate paper converter in the late ’80s. Then a year and a half ago, that paper converter company at 5 Appleton closed.

But now the building is in the process of being reborn. At least 50 local investors have contributed $760,000 to start Positronic Farms, a business that plans to grow large quantities of marijuana — if it secures a license to grow from the state and a special permit from Holyoke.

The three-member Massachusetts Cannabis Control Commission, in charge of regulating the burgeoning industry, will begin accepting applications for marijuana cultivation, product manufacturing, and retail operations starting Oct. 1. State Treasurer Deborah Goldberg is set to make her appointments to the commission by Sept.1.

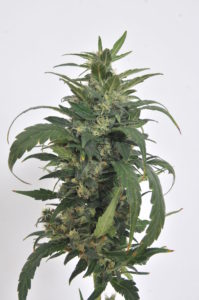

David Caputo, founder and president of Positronic Farms, said the business has signed a lease for 5 Appleton and right now it’s being renovated to fit the needs of the wholesale cultivation business.

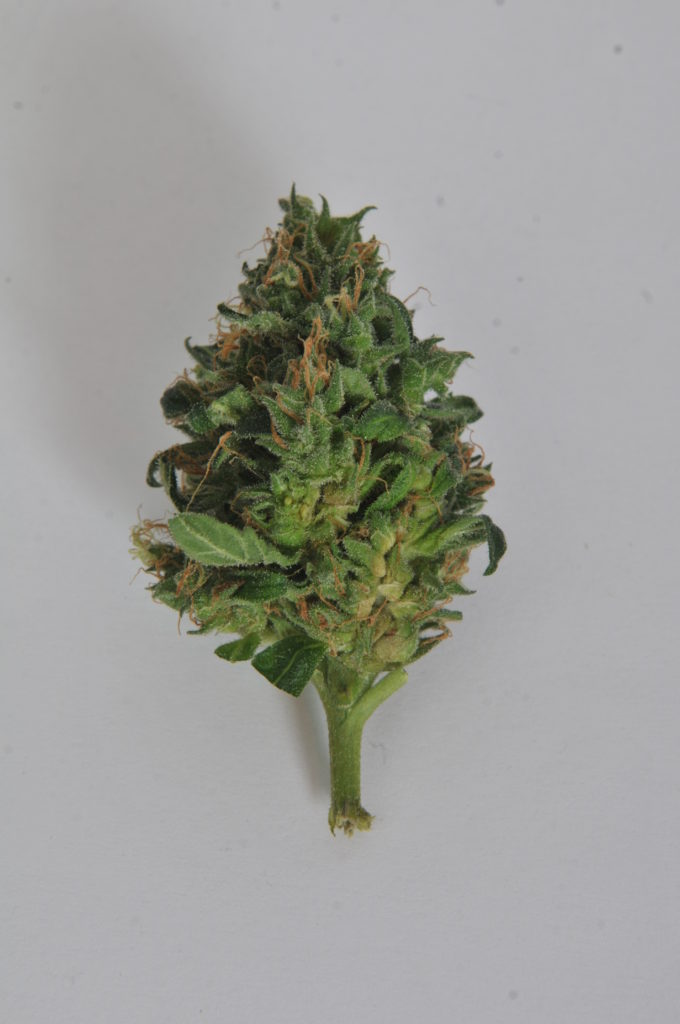

Caputo, of Holyoke, said he envisions separate growing areas for infant, adolescent, and adult marijuana plants across roughly five acres of space in the soon-to-be indoor greenhouse. Other areas at Positronic Farms would include experimental labs to create new strains of weed. The company has plans to keep about 2,000 marijuana plants growing in the facility at all times. He wants the business to be one of the biggest producers of marijuana in the region by its second year in operation.

“I don’t want to sell my product to individuals,” Caputo said. “I basically want to sell my product wholesale as if I had a brewery — I wouldn’t sell my beer to liquor stores; I’d sell them to liquor distributors. We’re not going to have any retail component. There’ll be nobody coming in and out of our building, it’s just going to be a warehouse locked away. Once a month a big truck comes and takes a big load away.”

But before any of this can happen, the state has to set ground rules for recreational cultivation and sales and communities have to decide whether they are going to welcome or reject the marijuana industry.

Officials in Holyoke, Northampton, Springfield, Greenfield, Amherst, and Easthampton said they’re being cautious about formulating any city ordinances or regulations for weed before state politicians make promised changes to the recreational marijuana law voters approved in November 2016. Most have adopted a “wait and see” approach until the law has been officially amended. However, there are differences to how each community is tackling this issue.

The state Legislature agreed in December 2016 to delay retail marijuana shops six months beyond the July 1, 2017, date voters approved at the ballot. The move was made in an effort to grant state officials more time to answer lingering questions, according to State Senate President Stanley Rosenberg (D-Amherst). Some of those include: how much control municipalities have in limiting weed in their communities; what’s a fair tax rate; and what’s the most responsible way to protect children from pot advertising.

Caputo, also the owner of Holyoke-based marketing company Positronic Design said he’s been dreaming about starting a recreational marijuana cultivation business for the past 25 years, but because it was illegal before Question 4 was approved, that dream went unfulfilled. Caputo said when he woke up the morning after the November 2016 presidential election, he was horrified of the reality of a Donald Trump presidency, but elated that his idea could finally bare fruit — er, flowers.

“I could only plan and wait during such times unless someone wants to go into illegal cultivation, which I did not,” he said.

Paul Borneo, master grower for Positronic Farms and an investor in the company, said he’s been growing marijuana for years and he’s glad “society finally caught up” in recognizing the value of the once illegal plant.

Holyoke was chosen as the prime location for the business due to the low costs for electricity and rent, Caputo said. About 60 percent of Holyoke’s power is created from its hydroelectric dam that draws water from the Connecticut River. The remaining power supply includes a lot of solar power.

That smaller carbon footprint aligns well with the green philosophy of Positronic Farms, he said. For example, instead of using pesticides, more than a million ladybugs will be released through the mill building to act as a natural pest control. The company is selling itself as “green grown green.”

Caputo said Holyoke’s inexpensive business space and power are going to allow Positronic Farm to sell marijuana at a less expensive rate than other wholesalers.

“The national average for a pound of marijuana is about $800 in cost. We’re going to be able to do it for about $150 in cost,” he said. “So, in other words: We’re going to crush the other kids.”

Caputo said he believes the business could begin operating anywhere from six months to a year and a half. He’s ready to start as soon as a cultivation license is secured from the state and a special permit is granted by the city.

Caputo with his Positronic investors showing off the marijuana cultivation area. Photo by Chris Goudreau

But in Holyoke, some officials oppose allowing recreational marijuana growing operations in the city.

Holyoke City Council President Kevin Jourdain, an opponent of recreational marijuana, said he doesn’t believe the city should promote the weed industry because it sends a hypocritical message. He thinks the marijuana industry should be viewed with a more critical eye, like tobacco. And the city recently took a stand against big tobacco, Jourdain said.

In June 2015, the city raised the legal age to purchase tobacco from 18 to 21, which Jourdain said he believes was a message that Holyoke acknowledges the health impacts caused by smoking. The city council crafts ordinances related to zoning, which can either be approved or vetoed by the mayor, he said. The existing medical marijuana laws in Holyoke require companies to be located within industrially zoned areas and to receive a special permit to operate.

Jourdain said Mayor Alex Morse thinks recreational marijuana is a “golden scratch ticket” for the city, but he isn’t convinced.

“Everybody thinks this is a really, really bad idea,” he said noting many state and municipal officials across Massachusetts came out in opposition of legalization prior to the vote.

Morse said he believes a regulated and taxed system for recreational weed is safer for people and would also help drive out the black market.

“Prohibition has not worked. It’s caused a lot of damage. It’s imprisoned a lot of people,” Morse said. “The War on Drugs has been a massive failure. We spent billions of dollars and we have really nothing to show for it other than a broken criminal justice system and locking up mostly people of color that are still in jail or have lives that are more challenging when it comes to finding jobs or going back to school.”

In the downtown area of Holyoke there is more than 1.5 million square feet of building space at old paper mills that could be utilized to grow marijuana, Morse said.

“The pitch we’re making for recreational marijuana growing and dispensing is the same pitch we would make for any industry. Marijuana just happens to be the crop and the product that has the highest return on investment at the moment,” he said. “There was a recent profile in The New York Times about how the industry has led to a real estate boom in those states where legalization has moved forward.”

The burgeoning industry could create hundreds of jobs in Holyoke alone, Morse said, but one of the challenges for recreational marijuana in the city will be where to put it.

The City Council is gathering input from residents about recreational pot in the city and has hosted one public hearing thus far, Jourdain said. A second public city meeting on marijuana is slated for April 28 at 6:30 p.m. at City Hall.

For people age 21 and older in Massachusetts, it is legal to possess some marijuana and use it. Adults are also allowed to grow six marijuana plants in their residences, with the homeowners’ permission. They can share marijuana legally, too. However, buying pot, pot plants or seeds to grow marijuana is risky — and illegal. But a friend can give an adult seeds as a gift. Recreational weed won’t be sold legally in Massachusetts until July 1, 2018 at the earliest.

State officials are working on busting up this limbo and making the laws around recreational marijuana concrete.

“The first area that we’ll be looking at are things that need to be clarified and fixed right away … like governance,” Senate President Rosenberg said. “Communities have said they don’t understand what their authority is and how to execute that authority to the extent that it is given, which in the law the secretary of state has put forward a proposal to clarify.”

He said the work politicians are doing now is “not intended to undercut or undermine the implementation of the bill, it’s intended to make sure we get it right. The voters have spoken.”

The first changes to the recreational marijuana law approved by voters — by a 53 percent majority in 2016 — would likely appear before Gov. Charlie Baker in early June, Rosenberg said.

Meanwhile, in Northampton, the city’s zoning was updated after medical marijuana became legal in 2012. With recreational marijuana, the city is waiting on the state before crafting zoning ordinances in regards to that industry, Northampton Mayor David Narkewicz said.

“We already have fairly well established zones in our city for obviously residential where we don’t allow any kind of retail,” he said. “In many ways we’ll be looking at it as retail like any other retail business.”

The city’s experience in working with New England Treatment Access (NETA), a medical marijuana facility on Conz Street, may be informative in the future, he said.

“It’s not in the heart of downtown, but walkable to downtown, and that seems to have worked out well in terms of their business and we haven’t had any issues or problems with it,” Narkewicz said. “It kind of fell under our current zoning for where dispensaries could be located. That will be one of the issues that we’ll have the Planning Board look at if they review zoning to find out where exactly these new retail recreational marijuana outlets would fit within our current zoning.”

The Valley Advocate submitted a request for comment to NETA asking if the company had plans to enter into the recreational marijuana industry, but have yet to receive a reply.

Other communities in Western Massachusetts are taking different approaches. Springfield Mayor Domenic Sarno is calling for the city to create tight law enforcement controls on recreational marijuana, while in March, the city of Greenfield decided to place an 18-month moratorium on the establishment of any pot businesses in March as a way to grant officials more time to draft ordinances. The town of Amherst isn’t creating any major long-term development plans centered on recreational marijuana, but hasn’t discounted the idea of pot shops either, said the town’s economic development director. In Easthampton, city officials are hosting public meetings to get feedback from residents about the issue.

Springfield has the most experience with recreational weed so far — for a while, the city had a recreational marijuana “club.” In a March letter to members of the state Joint Committee on Marijuana, Springfield Mayor Sarno said the city has enacted restrictions through zoning ordinances in order to allow the city to have more time to respond to state regulations.

“While I respect that a majority of Springfield’s voters approved the legalization of marijuana, I believe that the Legislature should amend the act so as to accomplish its purpose in a manner consistent with municipal home-rule powers,” he said.

Sarno also alluded to the closure of Mary Jane Makes Your Heart Sing, a smoke shop at 1865 Page Boulevard that was giving its customers gift samples of marijuana after they paid a $20-$50 admission charge. After the city caught wind of the business, the legal department issued a cease and desist order on March 1 threatening undefined police “enforcement” if the business did not comply.

“The business was not being properly run, but we were able to shut them down. The difficulty will continue in allocating scarce resources to monitor and enforce future attempts to circumvent the law,” he wrote.

Springfield Police Sgt. John Delaney, the department’s public information officer, said at Mary Jane Makes Your Heart Sing the amount of money that customers paid at the door impacted how much marijuana they received.

“I asked [one of the managers], ‘If someone came in here with no money and just wanted to look at a T-shirt on the wall and they walked out the door would you gift them marijuana?’ And he said, ‘No.’ And I said, ‘Well you’re selling it,’” Delaney said.

He said there are no other types of businesses that he knows of in Springfield that have been handing out marijuana in exchange for an entry and that Mary Jane Makes Your Heart Sing “hasn’t been open since.”

However, Selina Christian, a co-owner of Mary Jane Makes Your Heart Sing, posted on the business’ Facebook page from her personal account that the shop had re-opened on April 4.

Multiple attempts were made by the Valley Advocate to contact store owners, but there was no response.

In Greenfield, where voters approved Question 4 by 64 percent, Mayor William Martin said he hasn’t received any negative feedback from residents about the decision to institute an 18-month moratorium on recreational marijuana.

“The Board of Health passed an ordinance maybe three years ago and it limited the sale of tobacco products and restricted in-house sales of coffee and food with tobacco,” Martin said. “I don’t know if we’re going to have to change that ordinance if the state comes up with a different type of law that will supercede our ordinance on tobacco.”

He said the moratorium was put into place in order for the city to “be informed before we make another decision.”

The town of Amherst is looking to compete with other communities in the Pioneer Valley when it comes to attracting recreational weed businesses, but isn’t planning on changing its economic development plans based on the new industry, Amherst Economic Development Director Geoff Kravitz said.

“We’re trying to stay competitive and say, ‘Hey, if it’s going to happen nearby and there’s a market we might as well figure out how we could do it responsibly in town,’” he said. “The support from the ballot measure was overwhelming. We see that it’s something that the community wants and that’s why we’re trying to be responsive to the voters.”

Easthampton residents have engaged in a dialogue with public officials about recreational marijuana retail outlets at one public meeting thus far. City Planner Jessica Allan said the resounding message from residents has been to “keep it out of downtown,” with more people amenable to keeping recreational pot businesses in mill and industrial areas.

The city’s Planning Board will also soon consider a moratorium on retail businesses that sell recreational marijuana.

Justin Bergeron, co-owner of Head Eaze, a shop that sells pipes and vaporizers in downtown Easthampton, said he’s thinking about applying for a license from the state to sell recreational marijuana at his shop, which moved from North Adams to Easthampton two months ago.

“It might be something out of our price range when the time comes,” he said. “I’m not sure what the regulations are going to be.”

Since moving to Easthampton, the business has been welcomed by customers — half of which are people over the age of 50 — as well as the community, Bergeron said.

“Even members of the Planning Board have come in after we’ve opened up to check us out … The town’s been really great. We haven’t had any negative things that we’ve noticed,” he said.

The shop started as a clothing store at its North Adams location and gradually started selling pipes and other smoking products, he said. Before legalization of recreational weed, Bergeron never talked about marijuana in his store.

“I can speak freely with people. I can advocate with them about the benefits of pot; have conversations about growing things like that and people can ask me questions. I don’t have to tell them that they can’t say things like that in the shop,” Bergeron said. “It’s very liberating because people have hide something so benign and so beneficial even. For that to be criminalized for so long and for this whole large section of society to be viewed as or feel like a criminal just because they choose to smoke a joint instead of getting shitfaced; It’s just ridiculous.”

Contact Chris Goudreau at cgoudreau@valleyadvocate.com.