In my column in last week’s Advocate, a preview of the Valley’s summer-theater season, I reported that many of the area’s upcoming shows reflect, indirectly or explicitly, “the political landscape we are all traversing these days.” Sure enough, the first two summer shows out of the gate – not in the Valley but in Pittsfield and Hartford – do indeed invite, and in one case compel, reflections on our perilous present day through the prism of traumatic historical eras.

The title character in the show now playing at Barrington Stage Company (through June 10) is William Kunstler, the radical attorney who in the 1960s took up Clarence Darrow’s dragon-slaying mantel (and his rumpled sartorial style) as defense council in some of the era’s epoch-making political trials. Kunstler’s career, as outlined in this first-person dramatic profile, included representing Civil Rights-era Freedom Riders, Vietnam-era protesters, rebellious prison inmates and insurgent Native Americans.

Jeffrey Sweet’s Kunstler isn’t a one-person show, but it easily could be. It imagines the lawyer addressing a campus audience in 1995, while outside the lecture hall a chanting crowd berates him for having betrayed his radical ideals in later life. (When we enter the theater, we’re greeted by leaflets urging a boycott of the talk and a hanging effigy figure marked “Traitor.”)

Jeffrey Sweet’s Kunstler isn’t a one-person show, but it easily could be. It imagines the lawyer addressing a campus audience in 1995, while outside the lecture hall a chanting crowd berates him for having betrayed his radical ideals in later life. (When we enter the theater, we’re greeted by leaflets urging a boycott of the talk and a hanging effigy figure marked “Traitor.”)

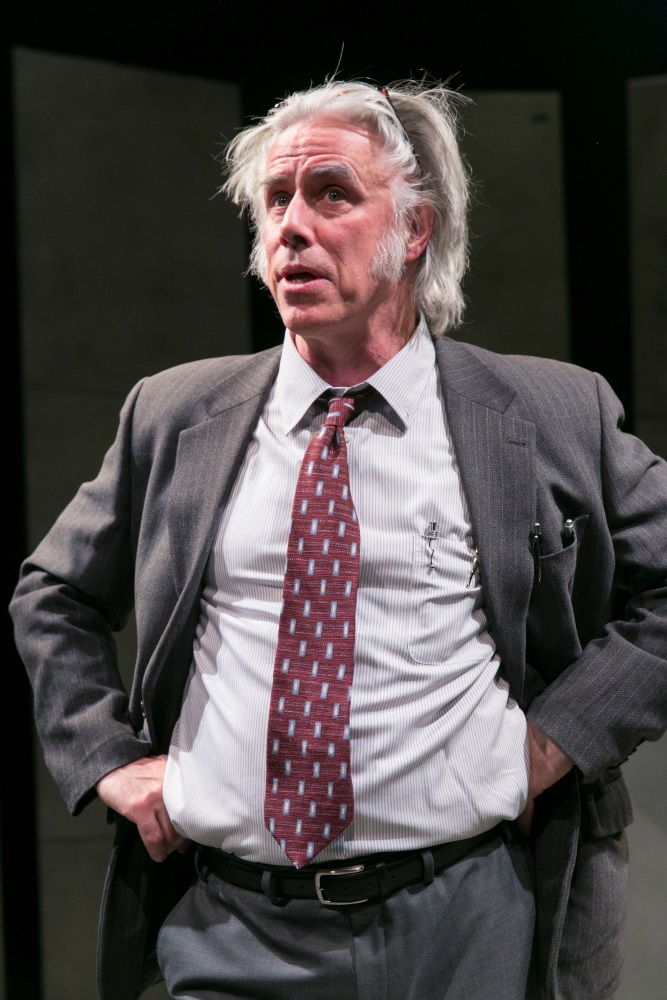

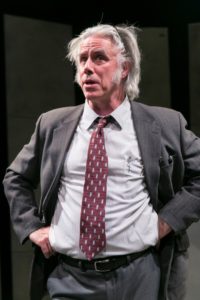

Most of the 90-minute piece, with spirited direction by Meagen Fay, is given to Kunstler’s discourse, a rambling recap of his career delivered in his trademark flamboyant style. Jeff McCarthy, a popular fixture at Barrington Stage, gives a high-energy chameleon performance as Kunstler, now clownish (he admits to being “a showman” in the courtroom too), now fervidly recalling the injustices he fought to counteract.

Before and after his sometimes bizarre but often passionate and always entertaining performance, Kunstler spars with the black student who agrees with the protesters and rather grudgingly introduces his lecture. Erin Roché is an effective foil in these brief exchanges, but her character is little more than a prop and sounding board in what, as I said, is essentially a classic one-person show – not a true drama but an autobiographical journey in the company of a unique personality whose life epitomized the American spirit of dissent and justice that is again under attack today.

Chekhov in Sussex

Like Kunstler in a way, George Bernard Shaw’s Heartbreak House (through June 11 at Hartford Stage) isn’t really a traditional play but, in this case, a lively collision of attitudes and expectations over matters of love, lust, ambition, memory and, oh yes, the future of civilization – or at least, civilization as practiced by the British upper classes. Shaw wrote it during World War I and set it in the summer of 1914, just before the reckless arrogance of the European powers plunged the continent into catastrophe.

Presented in the guise of one of those English-country-house comedies of manners, it’s an extended (and entertaining) metaphor of the hidebound social and political systems that Shaw believed had spawned the war and which, he hoped, were nearing their demise. The subtitle of Heartbreak House is “A Fantasia in the Russian Manner on English Themes,” a nod to Chekhov’s end-of-a-way-of-life tragicomedies.

The titular abode is that of an eccentric retired seafarer, Captain Shotover, who has refashioned it to resemble the bridge and poop deck of his old sailing ship. (Colin McGurk’s multi-level set is a masterpiece of whimsy and detail.) Also in residence are the captain’s daughter Hesione, a bohemian in the Virginia Woolf mode, and her faithless husband Hector. In one of his serial flirtations he has bedazzled young Ellie, one of Shaw’s sensible “modern” heroines, who’s on the verge of marrying the wealthy capitalist who saved (and then, as it turns out, ruined) her father’s business.

The titular abode is that of an eccentric retired seafarer, Captain Shotover, who has refashioned it to resemble the bridge and poop deck of his old sailing ship. (Colin McGurk’s multi-level set is a masterpiece of whimsy and detail.) Also in residence are the captain’s daughter Hesione, a bohemian in the Virginia Woolf mode, and her faithless husband Hector. In one of his serial flirtations he has bedazzled young Ellie, one of Shaw’s sensible “modern” heroines, who’s on the verge of marrying the wealthy capitalist who saved (and then, as it turns out, ruined) her father’s business.

In Darko Tresnjak’s otherwise graceful production, that character becomes the play’s key figure. “Boss” Mangan is a grasping, strutting, ruthless entrepreneur on the verge of extending his grasp into the realm of politics – in other words, a 19th-century Trump. And to make sure we get the parallel, Andrew Long brings to the role a pouty smirk and a thatch of yellow comb-over – which gets a laugh of recognition when he first appears but then becomes a distraction.

The other weekend guests are Shotover’s other daughter, Ariadne, who’s the snooty wife of a lord, and her brother-in-law, a rather perfunctory and superfluous character (as is an intruding burglar who has been cut in this production, which could still use a little more trimming). What plot there is follows a chain of infatuations that parody Wildean farce while indicting the shallow lives of the leisured classes.

But ultimately the play asks, as we ourselves are anxiously wondering these days, Whither the Ship of State? Shaw’s largely unresolved ending, set in a moment of peril and excitement, signals his grim hope that the cataclysm then wracking his world would sweep away an untenable status quo.

But ultimately the play asks, as we ourselves are anxiously wondering these days, Whither the Ship of State? Shaw’s largely unresolved ending, set in a moment of peril and excitement, signals his grim hope that the cataclysm then wracking his world would sweep away an untenable status quo.

In the very able nine-member cast (there’s also Ellie’s father and the obligatory waspish maid) I particularly enjoyed Miles Anderson’s Shotover – a quirky, volatile crackpot who’s saner than anyone – along with Dani De Waal and Charlotte Parry as Ellie and Hesione, the one doggedly purposeful, the other adamantly blasé. The production is handsome (Ilona Somogyi’s three acts’ worth of costumes are a stylish treat) and even if we don’t choose to indulge in Shaw’s metaphorical undertones, we can luxuriate in his quick-witted language and invigorating ideas.

Kunstler photo by Carol Rosegg

Heartbreak House photos by T. Charles Erickson

If you’d like to be notified of future posts, email StageStruck@crocker.com