It looks like a normal courtroom, but once a week, Courtroom 10 in Hampden District Court hosts a legal session that is anything but typical.

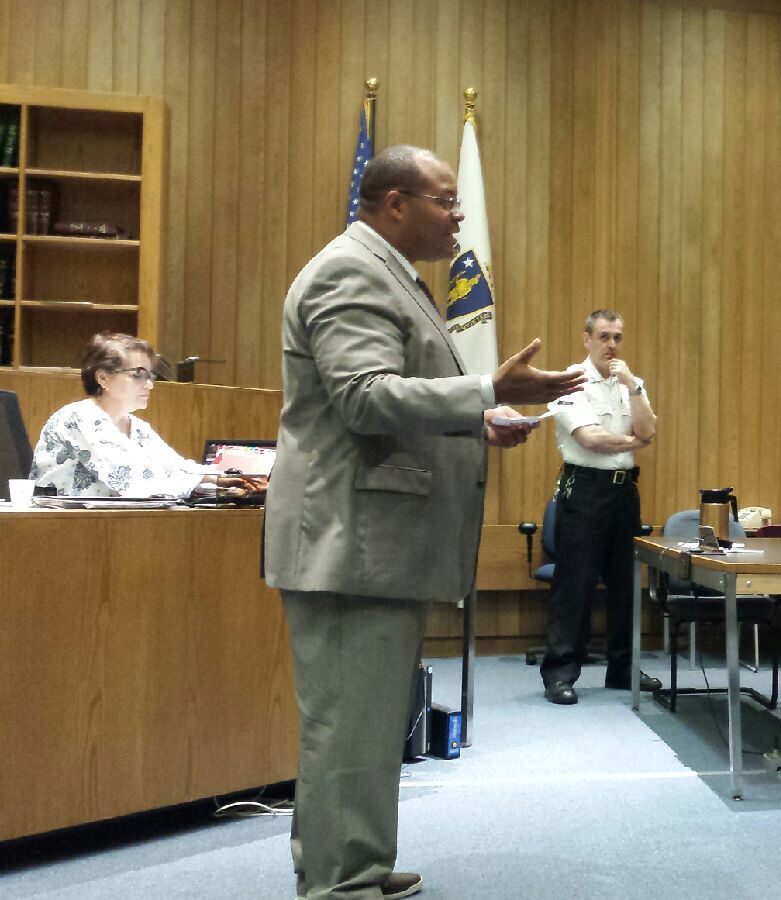

Rather than be shamed from the bench for crimes committed, a group of recovering addicts speaks to a judge eye-to-eye and receives a round of applause for the progress they have made. Gone is the judge’s austere black robe. He just wears a suit during the session.

The Springfield drug court, a more common name for the Court Assisted and Supervised Treatment Session, began in January. The specialized court is a way for Hampden County to direct non-violent drug offenders to treatment programs instead of prison. The goal of the year-long program is to break the cycle of addiction (despite overwhelming difficulties in getting off addictive drugs) and get offenders’ lives back on track.

Statewide, there are 46 specialty courts, 27 of which are drug courts, according to information from the state Trial Court. Specialty courts, including drug courts, are specialized court sessions that identify individuals with underlying needs.

Using a team approach, the court provides supervised probation and mandatory treatment, along with random drug testing. Participants are required to go to the weekly court sessions, where the judge will respond immediately to any issues with the treatment, or lapses along the way.

Among the participants who attends a recent session — in all, there are eight people involved — is Michelle Jackson, a 34-year-old mother who grew up in Chicopee and now lives in a recovery center in Springfield.

Among the participants who attends a recent session — in all, there are eight people involved — is Michelle Jackson, a 34-year-old mother who grew up in Chicopee and now lives in a recovery center in Springfield.

“I’ve been using the last 10 years,” she says. “I’ve destroyed everything.”

Jackson said she first got access to drugs at age 18, when she says her mother gave her morphine. Later, she began sniffing heroin. Police found out and her daughter was taken.

“I couldn’t handle that so I kept using,” she said.

Her first arrest came in 2010 for drug possession, and that led to jail time. Drugs have brought Jackson before judges since that time, including most recently for an arrest in March. Unlike the other arrests, however, the spring incident happened at a time when the Springfield Drug Court was up and running.

Participants must have had an arrest to participate in the program and must be approved. They also must volunteer to be a part of the drug court. Those who commit violent crimes or who have outstanding convictions in other jurisdictions, cannot participate. The program is broken up into four phases, and generally takes a year to complete.

“It is truly amazing,” Jackson says of the program. “I’m used to being sent away. Now I’m rebuilding my life and getting back in touch with myself.”

Judge Charles Groce III presides over the sessions. Absent is the black robe he wears for other occasions, and rather than sit behind the high desk flanked by law books, he stands on the floor and speaks eye-to-eye with the people over whom he is presiding.

Judge Charles Groce III presides over the sessions. Absent is the black robe he wears for other occasions, and rather than sit behind the high desk flanked by law books, he stands on the floor and speaks eye-to-eye with the people over whom he is presiding.

When Groce calls Jackson up to the bench, he asks her how she is before proceeding to the matter of an alleged probation violation. Following a recommendation by Jackson’s attorney, and supported by the probation department, Groce agrees to terminate the violation proceeding because it did not involve using drugs.

“We recognize in this program that not every step is going to be a positive step,” Groce says. “This is not a gift. This is something that was earned.”

Following the decision, and with Groce’s encouragement, Jackson reads a poem to those assembled. Her voice is clear, though it quivers with emotion during some lines about how her habit has affected her family.

“If I keep using, I’m just living to die, but deep down all I really feel is I’m dying to live,” she reads. “I sold my soul for dope, turned around and asked, ‘What else can I give?’”

Groce, as he often does, calls for a round of applause.

“I was speechless the first time I heard it, and now I have even less to say,” he says.

He reminds Jackson that the probation and other court officers are on her side. “We are all members of ‘hashtag Team Jackson,’” he says.

The participants are a diverse group, with both men and women and including individuals who are black, white, and Hispanic. Each approaches the bench, in turn. Each receives a round of applause. One — 57-year-old Springfield resident Pedro Alicea — Groce calls a “rock star” for the progress he has made in fighting his addiction and the 75 Alcoholics Anonymous meetings he has attended since beginning the program.

The participants are a diverse group, with both men and women and including individuals who are black, white, and Hispanic. Each approaches the bench, in turn. Each receives a round of applause. One — 57-year-old Springfield resident Pedro Alicea — Groce calls a “rock star” for the progress he has made in fighting his addiction and the 75 Alcoholics Anonymous meetings he has attended since beginning the program.

Alicea will graduate to phase two of the program on June 7, Groce says. The program has four phases, which track progress for each participant. Phase two involves demonstrating an understanding of addiction disorder and the need for recovery.

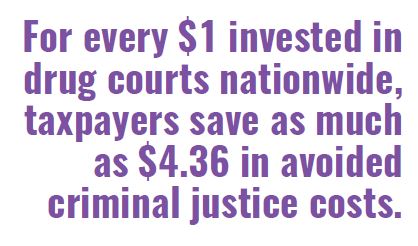

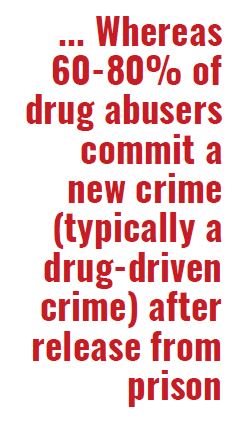

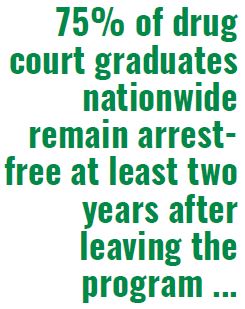

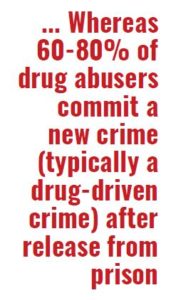

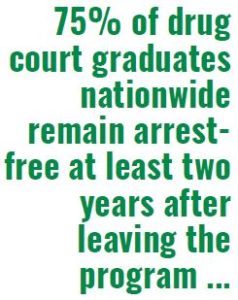

Drug courts in Massachusetts are seeing results. Of the 158 participants who have been out of the state program for a year or more, only 25.3 percent have had a new arrest within a year of their graduation, according to data from the Trial Court. Recidivism nation-wide for high-risk populations, including addicts, is about 60 percent.

Alicea, a Spanish-speaker, does not speak English, and spoke through a court-hired interpreter. “I have to thank you for all of the help,” he says.

Later, speaking to a reporter, Alicea says he agreed to be a part of the program to change his life.

“This is a program helping everyone so they won’t be sending people to jail,” he says through his interpreter. “This will help a lot of addicts. We do suffer when we are incarcerated.”

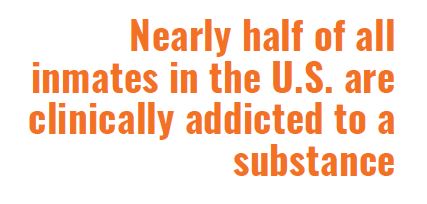

Data from the National Association of Drug Court Professionals backs up what Alicea says. Drug courts are six times likelier to keep offenders in treatment long enough for them to get better than traditional court proceedings, and family reunification rates are 50 percent higher for drug court participants.

Following the session, Groce and Chief Probation Officer Terence O’Neil speak about how the program came to be and what their hopes for it are.

Following the session, Groce and Chief Probation Officer Terence O’Neil speak about how the program came to be and what their hopes for it are.

Originally, the program was supposed to be set up in 2016, but there were delays because the prior chief probation officer retired during that year, according to O’Neil, who took his position in July.

“I think that the trial court wanted to make sure we were in the best position to succeed staffing-wise, so they beefed us up there a little bit,” he says.

Groce says he stole his more relaxed approach to presiding over the drug court from a Worcester judge he observed performing a drug court session.

“We had never done a drug court session before and we didn’t have discussions about robe or no robe or walk around versus not walk around, because those seem rather mundane,” he says. “But in actuality, they’re not. They’re very powerful.”

Groce, who was appointed as a judge by Gov. Deval Patrick in 2012, says he has seen the effects of addiction first hand, but that is not a rarity. Addiction affects so many people, he says.

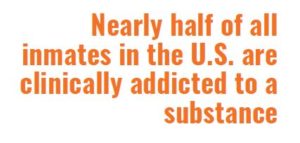

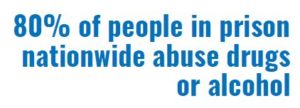

“If you spend any time at the Springfield District Court, down in Courtroom 1 or Courtroom 2, you’ll see that a vast majority of the people who come through this court in some way shape or form are related to substance abuse,” Groce says. “So there is a theoretical need for a much larger drug court.”

But there are not the resources for the program yet. While the probation department was tasked with putting together the drug court, they were not given any extra money or resources to make that happen, according to O’Neil.

O’Neil says there are five people in various stages of referral into the program in addition to the eight individuals already enrolled. The maximum capacity is 25, he says.

“If we figure out we can expand that cap, then we will,” O’Neil says.

Groce says the way that courts had been addressing addiction, by locking up addicts, has not been successful. And to those who might criticize the program as being “soft” on crime, Groce says that the program has the support of law enforcement and local sheriffs.

Groce says the way that courts had been addressing addiction, by locking up addicts, has not been successful. And to those who might criticize the program as being “soft” on crime, Groce says that the program has the support of law enforcement and local sheriffs.

“To the naysayers I would simply say, come see for yourself. Our door is open,” he says.

The future of the program may in some way be up to state politicians in Boston. One of them, state Rep. Carlos Gonzalez of Springfield, a proponent of getting the drug court started in his district, attends the session.

Gonzalez says he supported the formation of a drug court in Springfield because he had seen too many people go to jail over addiction or other mental health issues and that he’ll be a “loudmouth” in support of the drug court in the future, including the possibility of expanding the program.

“This has been the most rewarding experience of my legislative years,” Gonzalez says. “I saw what I hope is the future of courts and the direction we need to look at.”

Contact Dave Eisenstadter at deisen@valleyadvocate.com.

SOURCE: Information contained in the data points, in bold colors, came from the National Association of Drug Court Professionals.