Springfield, Massachusetts, was a big abolitionist hub during the days of the Underground Railroad — not that many people know this.

When talking about Massachusetts history, Western Mass isn’t well represented in historical texts — they’re more focused on Boston. And even less well represented is Pioneer Valley black history.

Springfield, Massachusetts, was an early safe haven for refugees. In 1783, Massachusetts was one of the first in the fledgling nation to abolish slavery, and Springfield, right on the border of slave-keeping Connecticut, was a safe spot for black slaves seeking freedom.

One must scratch beneath the surface to learn Springfield’s important black history. Graphic designed by Jennifer Levesque.

It’s difficult to find concrete proof of abolitionist history — particularly the Underground Railroad — because it was too dangerous to keep records.

“We know more about this after the Civil War when people published their memoirs. We don’t have such records for Springfield. Many abolitionists burned their records after the Fugitive Slave Act to be safe,” said Manisha Sinha, a University of Connecticut professor and author of The Slave’s Cause: A History of Abolition.

The paper trail is scattered across many kinds of records. To find such proof, Sinha said, you have to comb through church files, Census data, accounting books, store ledgers, legal proceedings, and newspapers, among other resources.

“Some records of fugitives were kept,” she said. “There are many pieces in archives, but many have been destroyed. In the case of Springfield I am not aware of any formal record but there is enough evidence that the free black community and church was involved in rescues.”

Often underrepresented, Springfield’s black history is a bit hidden. It’s only found by people who take the time to look. There’s a small exhibit in the Springfield History Museum, there’s the private nonprofit Pan African Museum in Tower Square, and you’d be hard pressed to find a marker for sites along the Underground Railroad — but there are a few.

“More work needs to be done to recover these histories from cities like Springfield,” Sinha said. “These places were strongholds due to black activism, but people view abolition as a white Northern affair, but they do not realize how radical it was because they are not aware of black activists and their involvement in the abolition movement.”

The Springfield Museums did not respond to requests for comment. The Springfield Historical Commission referred questions about local black history preservation to the museums.

History, if misconstrued and forgotten “can be part of the miseducation of a people that will have a them going to the back door even without being told,” said University of Massachusetts Amherst Afro-American Studies professor Amilcar Shabazz in one of his “Tell Me Something Good” faculty featured posts. History is a weapon, he said, it can unify, protect and inspire. Among the courses he teaches is Black Springfield Matters, a class focused on preserving Springfield’s black history while students learn research techniques. One such story his students unearthed was that of Dr. Ruth Loving (1914-2014), a Springfield resident who had an amazing military career. She began as a USO entertainer in Chicopee, then enlisted in the first National Guard unit for women — the Massachusetts Women’s Defense Corps — and learned Morse code during WWII when she worked on communications in a secret government facility in Springfield. In 1995 Loving would become a delegate to the White House Council on Aging under then-President Bill Clinton.

Preserving Springfield’s black history is important to a number of people, though not always easy. The Springfield chapter of the National Association of the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) has fought to keep the names of local black historical figures on buildings and areas that were named for them including the Mason-Wright Building, Alexander B. Mapp Building and the WW Johnson Life Center. In the late 1980s, they also worked to get Winchester Square renamed Mason Square in honor of Primus Mason, a wealthy black landowner who sold the downtown plot to the city in the mid-1800s.

A view of the Pan African Historical Museum in Springfield’s Tower Square, from behind the window. Although there are listed hours, the museum is only sometimes open.

The U.S. public education system is light on black history, according to Robert Romer, author of Slavery in the Connecticut Valley of Massachusetts.

“I run into people all the time that don’t want to believe slavery existed here,” he said. “There is a history of Massachusetts that was published in the year 2000 by UMass Press, I think. There is not a single mention in the whole book about slavery. In fact Massachusetts was the first of all British colonies in what is now the U.S to legalize slavery. Before Virginia or South Carolina, we did it first, we legalized slavery.”

The erasure of black history goes deeper than history books; it gets personal, said Bishop Talbert Swan II, president of the Springfield chapter of the NAACP. Swan said he was struck while casually looking up his birth announcement in the local paper.

“I went down to the main library and I was checking under micro film the Springfield newspapers in the 60s. I decided to check the papers around my birth,” he said. “I saw all these names but did not see mine. There was a lawyer I knew that had a daughter same day I was born. She was listed. I was confused.

“I asked my mother, ‘Why am I not on that?’ My mother said ‘Talbert you gotta understand that in 1965 the hospital maternity ward was segregated. They had white women and babies over here, black babies and women over there.’ When the paper at the time came to check the records to do the announcements, they got records of the white babies; they didn’t list the black babies. That’s here in Springfield.”

Preservation is one way to fight this kind of racial prejudice. So, that’s what we’re doing here now. One way to fight racial prejudice is to preserve and remember important black history, to not let prominent black figures and actions be whitewashed and forgotten. Springfield specifically had it’s share of prominent and important African-American residents that shaped the city as it is today. Here are some of their stories.

The Underground Railroad in Springfield

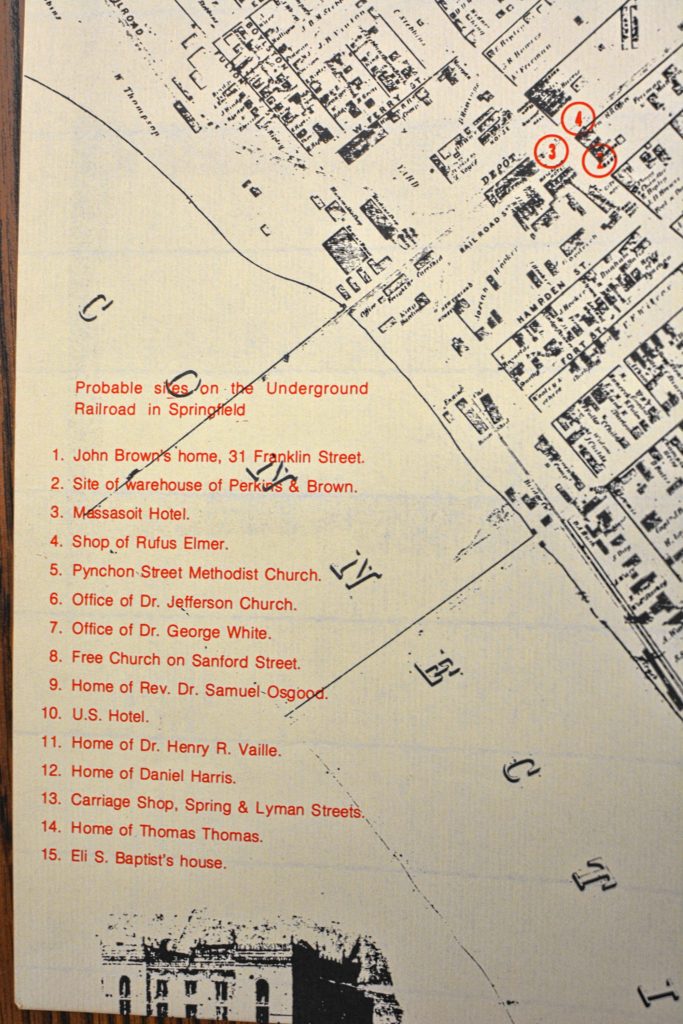

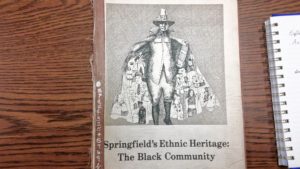

A close-up of a Springfield map identifying 15 possible “stations” along the Underground Railroad in the city’s downtown. The images is from “Springfield’s Ethnic Heritage.”

Being on the Connecticut river and having access to trains and railroads, Springfield was naturally a pit-stop for those escaping Southern slavery, according to Cliff McCarthy, archivist for the Wood Museum in Springfield.

Stopping in Springfield, fugitives would be directed to a number of safe spots, typically homes of free blacks, a place where refugees and runaway slaves could blend in. Springfield may have had eight to 15 stations on the Underground Railroad in its downtown, according to the Pan African Museum’s African American Heritage Trail and the research of local historian Joseph Carvalho III.

When the Fugitive Slave Act was passed in 1850, it caused an anxiety among Springfield’s 260 black residents that they would be hunted down and returned to slavery. Scouts would sit at train stations and watch the streets for people who might be slave hunters, prepared to warn fugitives and safe-spots of danger, said McCarthy. In one instance of Springfield protecting itself, McCarthy recalled a story by self-liberated slave William Wells Brown about “The King of Pain.”

When Wells Brown got to Springfield he “was escorted to a safe house … On the second floor he encountered a room full of African-American women who he describes as ‘Amazonian,’” McCarthy said. “They had this pot of boiling water they would pour out the window onto the slave catchers. They called it the King of Pain. If a slave catcher came to the town, there was a good chance someone would know about it. So the hunters stayed out of Springfield, it wasn’t fruitful and might get you killed.”

Homes weren’t the only stations on the Springfield Underground Railroad; churches and hotels operated safe havens as well. The First Church of Christ and the Free Church were instrumental. The First Church’s Rev. Samuel Osgood, a member of the Hampden County Anti-Slavery Society, would help direct slaves to safe spots in the city. He also organized the purchase of freedom for the last slave in Springfield, Jenny. No record exists of her last name. In 1808, residents of Springfield pooled together $100 and 19 people signed the bill of sale for Jenny.

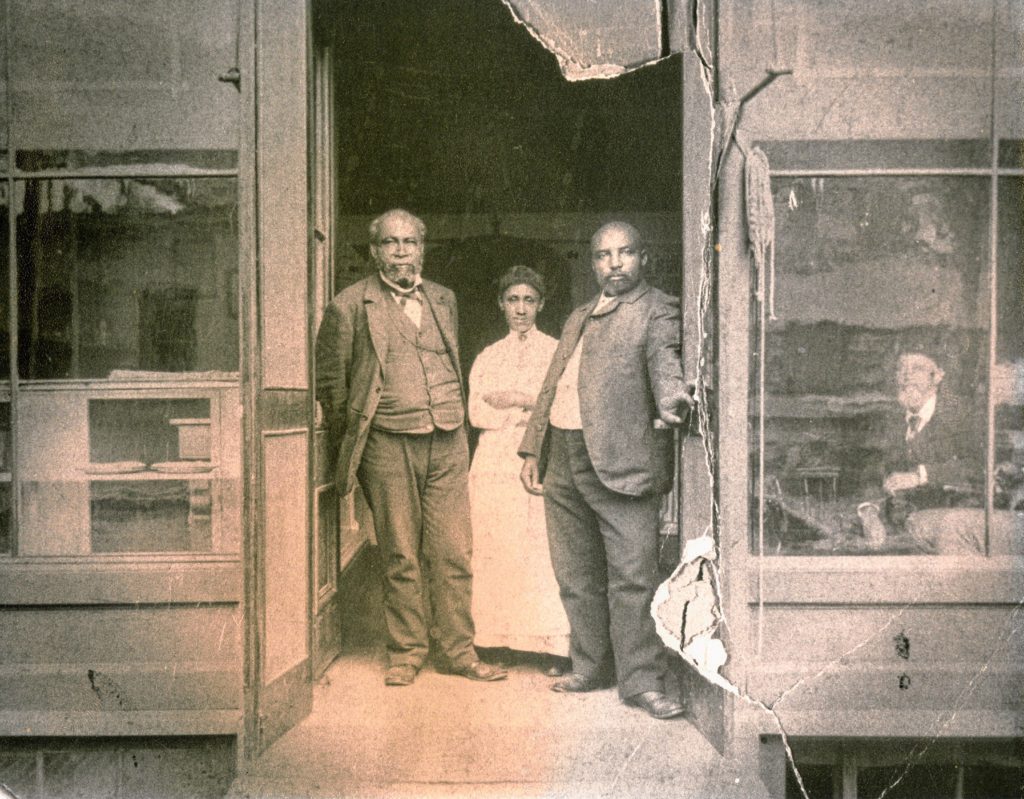

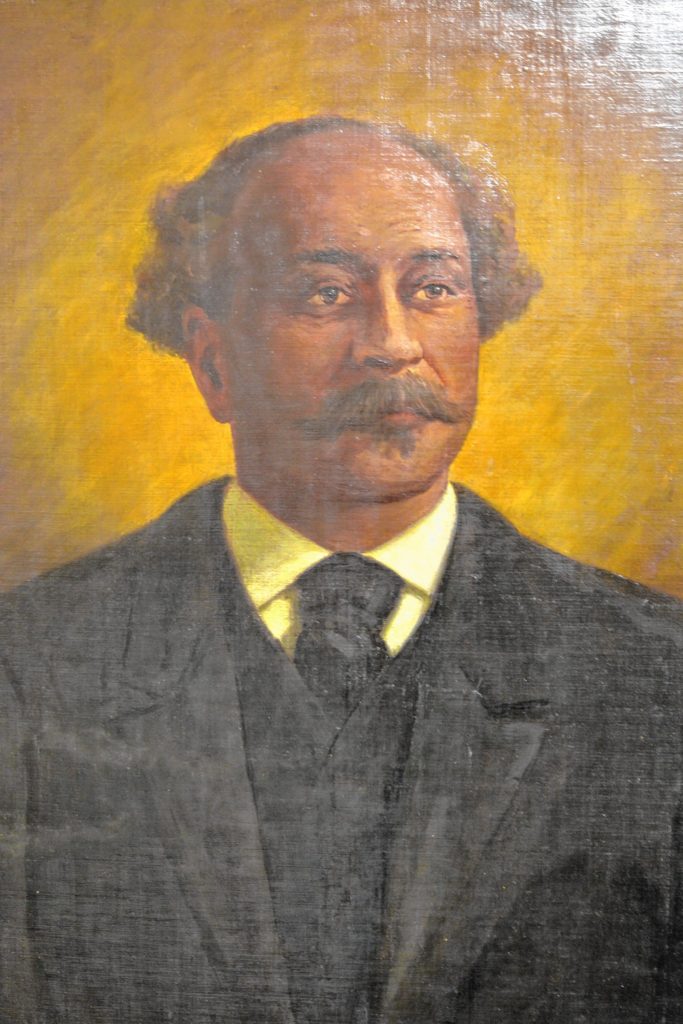

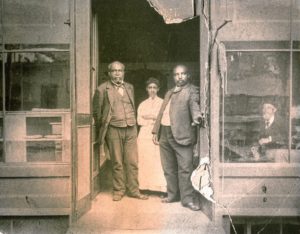

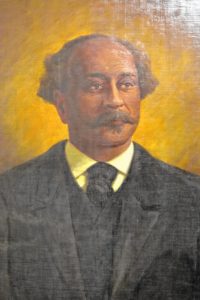

Thomas Thomas (left, circa 1830), an entrepreneur and friend of John Brown, at his popular Worthington Street restaurant. Courtesy of the Wood Museum and Library Archives in Springfield.

Springfield became a hub on the Underground Railroad due to its geography and established black community that could provide resources. Meanwhile, Connecticut passed a “gradual” abolition act in 1784 and Maine didn’t outlaw slavery until the end of the Civil War. Even in Massachusetts, where abolitionism was strong, black people were still in danger of being captured or kidnapped and sold back into slavery, local historians said.

Slave owners in Massachusetts would send their slaves to brokers in Maine to be sold in the South to offset lost money in the wake of the abolishment of slavery.

“From Hartford they’d have ‘boat parties’ they would invite people on the boat with music, and once the slaves were on the boat, the ship would sail down South. No one would report that stuff until after,” said Carvalho, author of Black Families in Hampden County.

In response to the Fugitive Slave Act, abolitionist John Brown formed the League of Gileadites. The Gileadites were an armed group of black men willing to fight and resist slave catchers with force. The Gileadites were just a part of the resistance, but a robust and important piece. There would be similar pacts throughout the area and, while many fled to Canada in wake of the FSA, Springfield had a notably militant stance.

“You had free blacks and abolitionists across the country resisting the law — not just sheltering and protecting people but also storming prisons, courthouses, literally rescuing enslaved people. Many people at the forefront of that were free blacks,” Sinah said. “Free blacks congregated in urban spaces and cities that were also quite prominent in terms of assisting the UGRR.”

Jupiter Richards

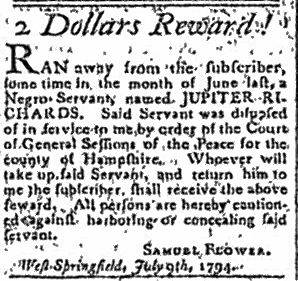

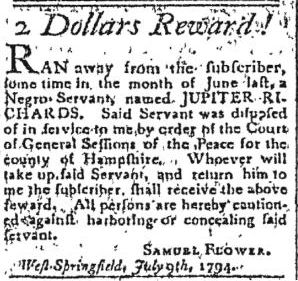

A copy of a runaway “servant” ad in a local newspaper from 1794, seeking the capture of black Springfield resident Jupiter Richards.

The story of Jupiter Richards shows that free black people in the 1700s had to not only worry about slavery, but the legal system, too. He was a free black man brought back into servitude.

Richards may have been born free or it may have been his Massachusetts military career that secured his liberty in the 1780s. He served for a total of seven years fighting for the colonial forces during the Revolutionary War, responding to the British in Lexington and Concord. His freedom and service didn’t stop Richards from becoming an owned man, though.

In Springfield, Richards married and had a family. He was a laborer, helping load and pile “shot and shells for the public,” for 1 pound and 19 shillings a week, according to McCarthy.

However, in 1789 the former Hampshire Chronicle newspaper reported that “Richards, a Negro, a resident in West Springfield” had been arrested for allegedly stealing 3 shillings worth of rye — a sum the 42-year-old Richards could have likely easily afforded. The fine and court costs that Richards was ordered to pay added up to be 4 pounds and 33 shillings, however. Unable to pay, Richards became an indentured man. His labor was sold, or “hired out,” to a Samuel Flower of West Springfield — for 20 years.

Due to scant documentation, it is unclear how Richards and Flower struck their deal or why the court accepted it, McCarthy said. He added that Richards may have been unaware of the number of years he was signing on for, as many African-Americans at the time were illiterate.

Richards didn’t stay to finish his two decades worth of servitude. About five years into the deal an advertisement for Richards’ capture — near identical to the runaway slave ads of the time — appeared in the Massachusetts newspaper the Federal Spy. A copy of the ad kept in the archives of the Wood Museum, reads:

“Ran away from the subscriber, some time in the month of June, a Negro servant named JUPITER RICHARDS. Said servant was disposed of in service to me in order of the Court of General Sessions of the Peace for the County of Hampshire. Whoever will take up said Servant, and return him to me the subscriber, shall receive the above reward. All persons are hereby cautioned against harboring or concealing said servant. Samuel Flower West Springfield, July 19th, 1794.”

McCarthy says he believes Richards was never captured or arrested and sent back to Flower. If Richards had been caught, there would be paperwork and documents from the court case that would follow as well as a receipt or paperwork referring to the reward paid out to the person who had caught Richards, he said.

Primus Mason

Primus Mason was a black real estate mogul and philanthropist in Springfield around the time of the Civil War. Upon his death, Mason donated land and money to hte city for the establishment of the Springfield Home for Aged Men. Today it’s called the Mason Wright Home.

Primus Mason was a black real estate mogul. As a free man back in the mid-1800s, Mason saved his earnings and invested them in land. He wound up selling much of that land to the city of Springfield — making Mason one of the wealthiest men in the area.

To make his fortune, Mason did whatever he could.

“He picked dead horses off the road through a contract with the city,” said Joseph Carvalho, author of Black Families in Hampden County. “Mason had a pig farm, he would feed the horses to the pigs, he then used his money to buy property and he became one of the biggest land speculators in the post-Civil War period.”

Having outlasted the lives of his immediate family, Mason put in his will that the majority of his wealth — $30,000 — would go to the creation of a home for poor and elderly men, but it had to be racially integrated. He died in 1892. At the time, there were no racially integrated retirement communities in the area, and while the retirement communities were expensive the Mason-Wright Retirement one was affordable.

Having outlasted the lives of his immediate family, Mason put in his will that the majority of his wealth — $30,000 — would go to the creation of a home for poor and elderly men, but it had to be racially integrated. He died in 1892. At the time, there were no racially integrated retirement communities in the area, and while the retirement communities were expensive the Mason-Wright Retirement one was affordable.

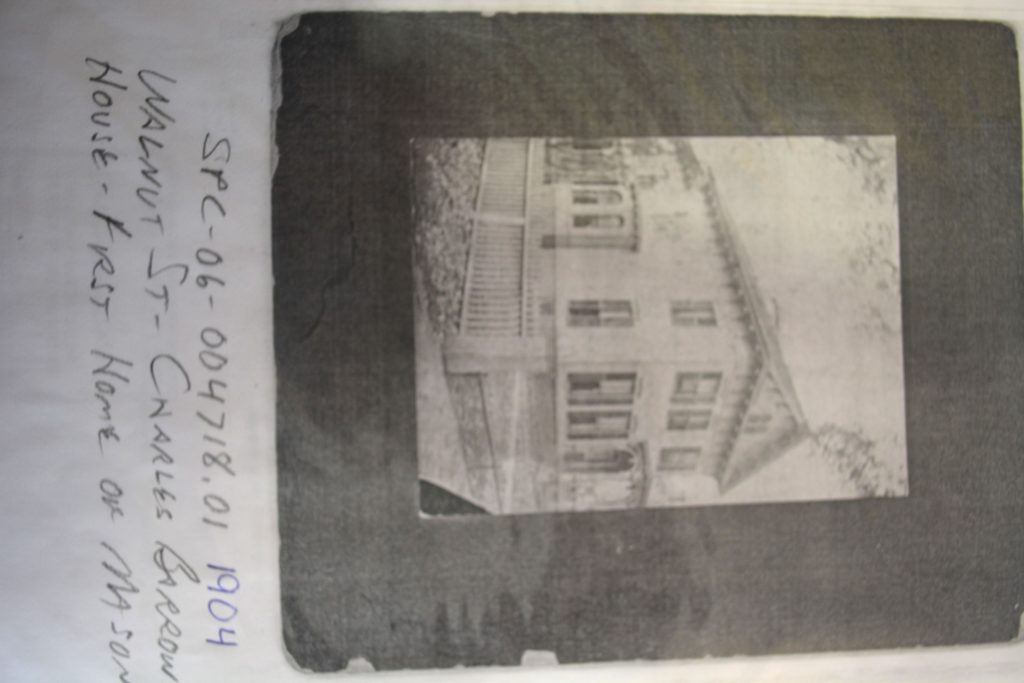

Most people may know Mason now through his memorial plaques at the Mason-Wright Retirement Community on 74 Walnut St. — right where it was originally built in 1903 — but much of the neighborhood of Mason Square was built on land Mason sold to Springfield.

Ruth Loving

Often confined to stories of the 1800s to the Civil Rights era, modern black history is often overlooked. For example, the story of Springfield’s Dr. Ruth B. Loving (1914-2014) was almost lost to the dust bin of history when Shabazz’s class took an interest in preserving her story.

Dr. Ruth B. Loving was born in Pennsylvania in 1914, but after moving around for awhile and marrying, Loving settled down in Springfield in 1939, where she would join the Springfield chapter of the NAACP. As World War II broke out, Loving volunteered to perform as an entertainer for the USO in Chicopee. Not long later she joined the Massachusetts Women’s Defense Corps, the first National Guard Unit for women. Loving then learned Morse code and worked in a secret facility in Springfield working communications for the government.

Years later Loving would volunteer to perform and entertain for troops during the Korean war, along with her three children, as well as performing religious music at church events. Loving would later become the Freedom Choir’s secretary.

Loving would also found and become the president of Chester Street Junior High PTA, after realizing there was no PTA at the school while her child attended. Loving went back to school herself and earned a B.A. with a concentration in Community Education and Media. In 1995 Loving became a delegate to the White House Council on Aging under Bill Clinton.

In recognition of her legacy and contributions to her community and her achievements, Loving was awarded an Honorary Doctor of Humanities Degree by the Springfield Theological Society. Loving did all of this while having multiple children and running a family. Eventually Loving passed away in 2014, but her legacy lives on and her history remains.

NAACP President Swan said he wants to see more preservation efforts like those in Shabazz’s classroom and in the Pan African Museum. Remembering history gives people a sense of place, pride, and value. Otherwise, the accomplishments — and worth — of an entire people can be taken for granted.

“They need to remember the contributions made by African-Americans in Springfield, and to not let that get lost in the great history of the city and while we are talking about William Pension and some of the great Springfield pioneers and politicians, we can’t let people like Mason get lost in the mix,” Swan said.

“We’ve got to preserve the great history of African-American pioneers in the city of Springfield as well,” he continued. “People need not forget that just as America has a long way to go towards racial equity, so does this city. We have yet got some more miles to run and battles to fight which makes the NAACP in 2017 — 99 years after its charter — just as relevant today as it was then.”

Contact Chance Viles at cviles@umass.edu and Kristin Palpini at editor@valleyadvocate.com.