My first exposure to Egon Schiele came via Deane G. Keller, an artist and professor whose figure drawing classes remain one of my most lasting memories of art school. We had been working on some hand studies when he suggested I might enjoy the Austrian artist’s work, and when class let out I cut through the trees to the school library to look up the man with the strange name.

The collection of work I found amazed me: drawings, watercolors, and oils, mostly portraits, and all filled with an expressiveness that, despite its impact, seemed effortless. Schiele’s control of line and form — and particularly in their interplay, so that even his sparest nudes felt spectacularly alive — made him an early example of the new movement that would be known as Expressionism.

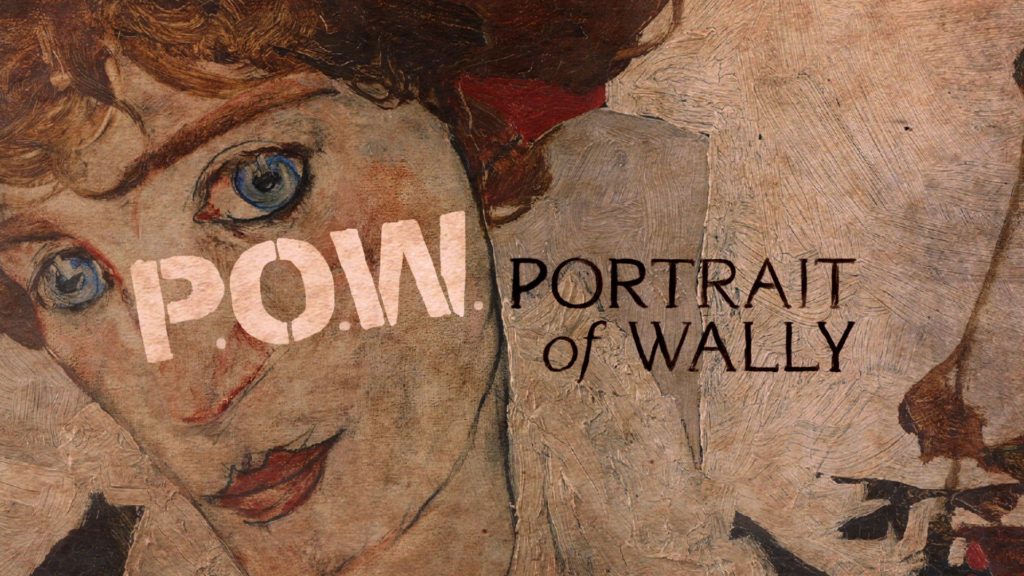

One of his best known works is Portrait of Wally, an oil-on-panel portrait of his young mistress Wally Neuzil. I remember the piece, but only recently learned its backstory. Now the pride of Vienna’s Leopold Museum, the painting’s history, like so many great European artworks, has a past tainted by another piece of Europe’s past: the Nazis.

This Sunday at 2 p.m., the Yiddish Book Center in Amherst will host a screening of Andrew Shea’s 2012 documentary Portrait of Wally, a deep dive into the painting’s provenance, and a big picture view of what great art can mean to family history and national identity.

The painting’s past came to light in 1997, when it resurfaced in an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan. With the painting on U.S. shores, the heirs of Lea Bondi — the Jewish art dealer who had been forced to give up the painting in 1939, while fleeing the German annexation of Austria, and whose previous attempts at retrieving the painting had failed — asked MoMA to hold the panel stateside. The museum refused. The heirs (Bondi died in 1969) found support from District Attorney Robert Morgenthau, who launched a criminal investigation that would keep the painting in limbo during the 13-year court battle that followed.

The legal wrangle was game-changing. Siding against the heirs were all the museums of New York (including, perhaps surprisingly, the Jewish Museum) as well as Ronal Lauder, the MoMA chairman who had founded the Commission for Art Recovery — an organization whose entire existence was dedicated to the return of looted art to its rightful heirs. In the end, the Leopold settled with the family, and the painting returned to Vienna — but not before forcing many museums to reconsider the histories of the works that made up their collections. And for Jewish victims of Nazi looting, whose memories and family history were broken up and sold to the highest bidder, the case brought new hope where it had long gone missing.

Portrait of Wally: Sunday, 2 p.m., the Yiddish Book Center, Amherst.

Also this week: Music fans get a couple of chances to escape the heat and soak up some tunes with performance films coming to area screens in the coming days. First up is the 2017 installment of the Grateful Dead Meet-Up at the Movies, an annual event that this year will screen at Hadley’s Cinemark on Tuesday night at 7 p.m. Timed to coincide with Jerry Garcia’s 75th birthday anniversary, the show will present a never before seen performance from RFK Stadium in D.C. (7/12/1989 for you Deadheads out there) along with some other musical rarities. The next night, Amherst Cinema will play host to a 7 p.m. screening of Hail! Hail! Rock ’n’ Roll, director Taylor Hackford’s (Ray) 1987 documentary about rock and roll pioneer Chuck Berry. Filmed as the icon was turning 60, the movie records a concert in Berry’s hometown of St. Louis, Missouri, where the guitar legend was joined by acolytes and admirers like Keith Richards, Robert Cray, and Eric Clapton. In the interviews between the tunes, other famous musicians from Bo Diddley to Bruce Springsteen expound on the enduring influence of Berry’s work.

Jack Brown can be reached at cinemadope@gmail.com.