The two mainstage programs at Jacob’s Pillow dance festival last week offered intriguing contrasts in modern dance envelope-pushing. And perhaps surprisingly, it was the simpler, solo show that delivered more variety and excitement.

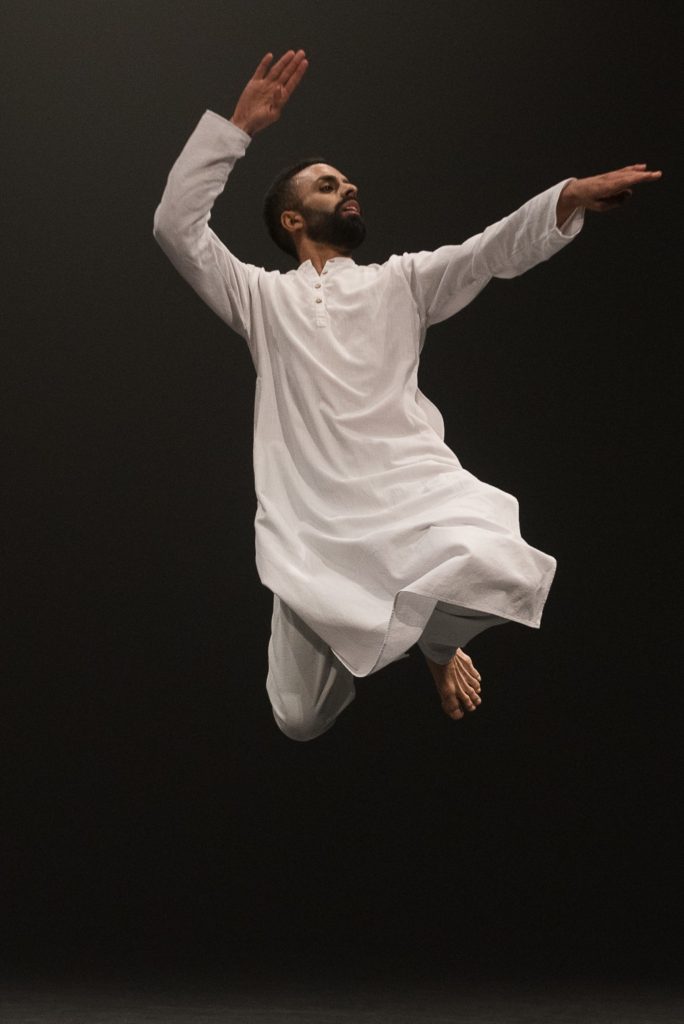

Aakash Odedra is an Englishman of Indian parentage who first trained in the dance traditions of his ancestral culture and then branched out into a stylistic kaleidoscope of world traditions. The pieces he performed, set by four different choreographers, reflected that breadth of influence.

Aakash Odedra is an Englishman of Indian parentage who first trained in the dance traditions of his ancestral culture and then branched out into a stylistic kaleidoscope of world traditions. The pieces he performed, set by four different choreographers, reflected that breadth of influence.

The first, Nritta (meaning “pure dance”), drew most strongly on his training in the classical Kathak dance form. To the polyrhythmic beat of a sitar, tabla and bansuri trio, he embodied the male/female duality represented by the gods Shiva and Parvati, along with Hinduism’s cosmic creation/destruction cycles and the terrestrial rhythms of birth and death. The combined delicacy and power of his movements found him floating in the air as if air were his natural habitat, then forcefully stamping the ground while slicing the air gently with his hands.

Hands played a key role in Cut, created by Russell Maliphant and lit by Michael Hulls in an inspired counterpoint of illumination and shadow. Tightly shuttered overhead instruments created narrow bars of light, into which the dancer dipped his hands in traditional gestures, the rest of his body barely visible in the surrounding penumbra – simple and thrilling.

Hands played a key role in Cut, created by Russell Maliphant and lit by Michael Hulls in an inspired counterpoint of illumination and shadow. Tightly shuttered overhead instruments created narrow bars of light, into which the dancer dipped his hands in traditional gestures, the rest of his body barely visible in the surrounding penumbra – simple and thrilling.

In the Shadow of Man, set by Odedra’s mentor Akram Khan, was based on the idea of the “inner animal” in all of us. It began with the dancer appearing to sprout proto-wings as tentative fingers twined upward from his shoulder blades. (Did I mention the guy is limber?) With occasional cries, snarls and barks, he “evolved” into other animal shapes – sinuous as a snake, lithe as a jaguar, articulated as an insect, embodying the choreographer’s core question: “Are we becoming more ‘human’ over time, or more like animals?”

The final piece was Constellation, set by Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui. A constellation, of course, is a human construct in which we form meaning out of separate points of light. Here, the stage was hung with small electric globes that Odedra, walking among them, illuminated one by one by touching them – whereupon they didn’t just sway on their cords but positively danced across the stage. Once again, his hands were the key.

The French-Canadian Compagnie Marie Chouinard gave a two-part program in which the soundtracks couldn’t have been more dissimilar, but whose movements clearly sprang from a single imagination.

First there was a cycle set to Chopin’s 24 Preludes for piano, played live onstage by Jean-François Latour. The ten dancers were garbed in sheer black with narrow bands across nipples and crotches, and hair tied into fauxhawks or kinky braids – which I read as a distancing of the 19th-century composer from his 21st-century interpreters?

First there was a cycle set to Chopin’s 24 Preludes for piano, played live onstage by Jean-François Latour. The ten dancers were garbed in sheer black with narrow bands across nipples and crotches, and hair tied into fauxhawks or kinky braids – which I read as a distancing of the 19th-century composer from his 21st-century interpreters?

The diversity of Chopin’s short pieces, cycling through all 24 key signatures and ranging from simple melodies to crashing rhythms to proto-modern dissonance, provided rich variety for the troupe’s interpretations in solos, duos, small groups and full ensembles. Sometimes the movements “illustrated” the music as dancers gestured in time to chords and runs, and sometimes they gave abstract expression to a mood.

For me, neither the parallels nor the abstractions were particularly interesting, but during the intermission my companion confessed that she hadn’t been able to really take in the dancing anyway, because of the music. A trained classical pianist, she found Latour’s playing “rushed, sloppy, and heavy on the pedal.” Aside from the technical deficiencies, altering some of the tempos to serve the choreography raised a recurrent issue around appropriating revered works for new purposes: When does reinterpretation become exploitation?

The program’s second half was described as a literal rendering of Mouvements, a little volume by the idiosyncratic Belgian author and artist Henri Michaux. The book, from 1951, consists of 64 pages of little black-on-white drawings and a long poem. Both words and images are free-associative, the drawings simple doodles and ink-blots but perhaps implying tiny emergent creatures. The poem is a tumult of disjointed phrases heading, as far as I could tell, toward the idea that humankind’s damnation and salvation lie in continual movement, either headlong toward catastrophe or in purposeful evolution.

The program’s second half was described as a literal rendering of Mouvements, a little volume by the idiosyncratic Belgian author and artist Henri Michaux. The book, from 1951, consists of 64 pages of little black-on-white drawings and a long poem. Both words and images are free-associative, the drawings simple doodles and ink-blots but perhaps implying tiny emergent creatures. The poem is a tumult of disjointed phrases heading, as far as I could tell, toward the idea that humankind’s damnation and salvation lie in continual movement, either headlong toward catastrophe or in purposeful evolution.

The suite of drawings was projected piece by piece onto the back of the space while the dancers responded to them, at first posing in imitation of the shapes, then giving mobile impressions of their implied dynamics – Rorschach in motion. This seemed to me little more than an exercise, a dance-class mirror-image improvisation. The piece was accompanied by a pounding, pulsating industrial underscore, created by Edward Freeman, that sounded (and felt) like being inside a huge machine. As in the Preludes piece, I found it hard to make a meaningful connection between the movement and the score.

It was a challenging program, pushing even the Pillow’s ultra-modern envelope, and I had to admire the matinee audience, some of them elderly folks you wouldn’t expect to see there. On the way out of the theater, we overheard a couple of passing conversations:

“I thought it was interesting.”

“Well, I thought it was abusive.”

“Did you like it?”

“It was brilliant, but I don’t know if I could say I ‘like’ modern dance.”

But bravo to those patrons, for venturing into unknown territory!

This week, two visiting compani es demonstrate the Pillow’s range of programming. In the mainstage Ted Shawn Theatre, Ballet Hispánico offers a fusion of classical, Latin and contemporary dance, including a flamenco-inspired piece, a contemporary take on Cuba’s national dance, and a Zarzuela investigating “the nuances of a kiss.” The intimate Doris Duke Theatre hosts Danielle Agami’s AteNine company in a program employing the Gaga movement vocabulary, including an exploration of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict set to a hip-hop and Iranian score.

es demonstrate the Pillow’s range of programming. In the mainstage Ted Shawn Theatre, Ballet Hispánico offers a fusion of classical, Latin and contemporary dance, including a flamenco-inspired piece, a contemporary take on Cuba’s national dance, and a Zarzuela investigating “the nuances of a kiss.” The intimate Doris Duke Theatre hosts Danielle Agami’s AteNine company in a program employing the Gaga movement vocabulary, including an exploration of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict set to a hip-hop and Iranian score.

Aakash Odedra photos by Christopher Duggan

Compagnie Marie Chouinard photos by

Sylvie-Ann Paré & Marie Chouinard

Ate9 photo courtesy of the company

If you’d like to be notified of future posts, email StageStruck@crocker.com