As president of the UMass faculty and librarians union, it is Eve Weinbaum’s job to fight for equity of all her union’s members. And beyond that, being a woman in a leadership position, she has thought long and hard about equal pay for equal work and how to achieve it.

The problem is a complicated one.

The data are out there and very clear. Women make, on average, about 80 cents on the dollar compared to men in the United States for full-time, year-round work, according to the Institute for Women’s Policy Research.

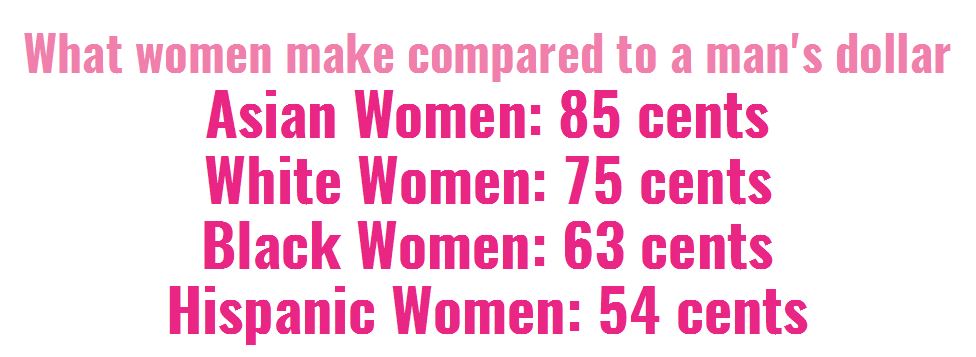

For certain minorities, the gap is more severe. For every dollar paid to a white man, Asian women make 85 cents on the dollar, white women get 75 cents, black women are paid 63 cents, and Hispanic women earn 54 cents.

Little data exists for transgender and gender non-binary individuals, but what studies have been done show that these populations experience pay gaps and significant discrimination in workplaces.

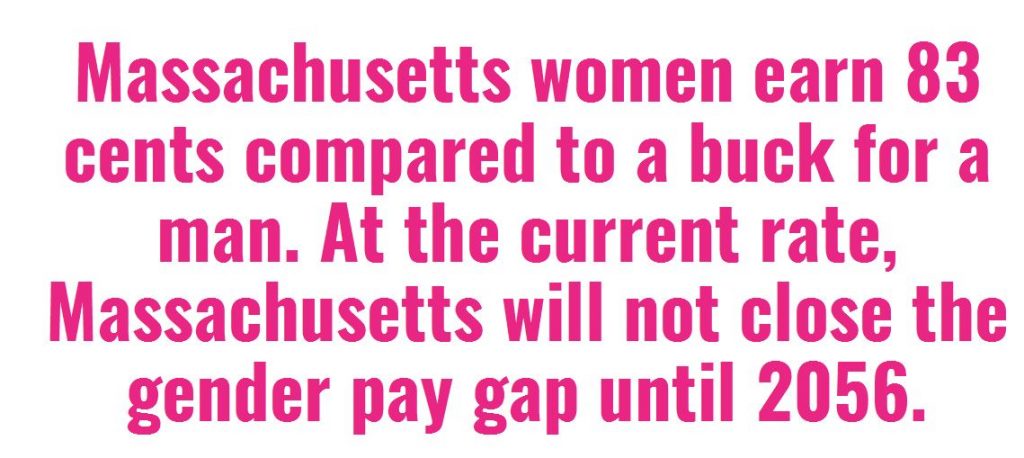

Massachusetts is far from the head of the pack with regard to closing the gender wage gap. The pay gap is projected to persist until 2056 in Massachusetts, longer than 16 other states and the District of Columbia, according to the Institute for Women’s Policy Research.

The American Association of University Women breaks down the pay gap to the state level — Massachusetts women earn an average of 83 cents to a man’s buck — and even further breaks the data down by Congressional district. This data shows Western Massachusetts doing worse than the state as a whole. In Congressman Richard Neal’s district, which includes the Springfield-Holyoke area, Berkshire County, and several communities in Hampshire and Franklin counties, women earn 82 cents to the dollar. Women in Congressman James McGovern’s district, which includes Worcester, Greenfield, Northampton and the communities in between, fare worse. They earn 79 cents to a man’s dollar — worse than the national average.

The state Legislature is working to address the pay gap. In July 2018, a law passed in 2016 will go into effect which requires equal pay for equal work. In the law are provisions barring employers from forbidding their employees to disclose salary information, asking for previous salary information, and retaliating against any employee for seeking equal pay.

But for Weinbaum, closing the pay gap is about more than equal pay for the same work, though she said that is an issue. Beyond that, however, are the way that women are closed out from management positions and also underrepresented in higher paying fields, like finance and computer science.

She pointed to a study of UMass faculty pay by the head of the university’s Institute for Social Science Research.

“It was really a microcosm of what you see in the economy as a whole,” Weinbaum said. “If you look at a department at a rank, you see little difference between men and women, though there is a difference …. Then if you go out a level, in the whole College of Social Sciences, the economics department has by far the highest salaries and by far the highest percentage of men.”

Looking at fields where women dominate the faculty, in places like the anthropology and sociology departments or in the College of Nursing, professors there have the lowest salaries. Computer science faculty, meanwhile, have some of the highest salaries and are mostly men, she said. That mirrors the pay and gender breakdown in the field for those professions.

While pay is a piece of the problem, promotion and hiring practices are also keeping women down, she said.

“The promotion piece is huge,” she said.

In graduate school science classes — where degrees can lead to high-paying jobs — there are about the same number of men and women enrolled, Weinbaum said. But as you look forward on the career track of faculty jobs in sciences — post-doc jobs, adjunct professors, associate professors, and then full professors, there are fewer and fewer women being hired and promoted into those positions every step of the way, she said.

In graduate school science classes — where degrees can lead to high-paying jobs — there are about the same number of men and women enrolled, Weinbaum said. But as you look forward on the career track of faculty jobs in sciences — post-doc jobs, adjunct professors, associate professors, and then full professors, there are fewer and fewer women being hired and promoted into those positions every step of the way, she said.

“We call it a leaky pipeline; there are women falling out at every step of the way,” she said, adding that fewer than 30 percent of full professors at UMass are women.

What Weinbaum has noticed during her time with the union is that men tend to be more aggressive about external funding and applying for grants, as well as seeking job offers from other universities that they then use to negotiate higher pay. Meanwhile, women are often saddled with caretaking roles outside the workplace, both for children and for older relatives.

Supportive colleagues are key, because at UMass fellow faculty members have a say in who receives tenure in their departments.

“Women in departments where colleagues are not supportive are in a much harder position,” she said. “We had a number of cases where women were denied tenure or promotions partly because their colleagues felt that when they needed time, especially caregiving time, that showed they were not able to keep up a level of productivity.”

As to solving the problem, fighting for pay equity and for things like family and medical leave really help women, she said. Having a union with access to all salary information and committed to fighting for pay equity is essential, she said. Also, while it is legal to speak to coworkers about pay, employers have a lot of leeway in dealing with employees they find disagreeable.

“Employment is still at-will. You can be fired for almost anything,” she said. “Collective action is the only way to get to these problems.”

Weinbaum herself has three children and worked hard to maintain her standing in her career. For the first two, she did not have any paid leave, and returned to work soon after they were born.

“It was crazy, I was sitting in class and I remember one day fighting so hard to stay awake because I had literally been up all night,” she said. “It is not surprising that people who don’t have [family leave] end up burning out and dropping out because you can’t keep that up.”

Weinbaum got by because she had supportive colleagues and a strong union, which eventually won paid family leave for its members. Weinbaum took advantage of that for her third child.

The Next Generation

Weinbaum’s middle child and oldest daughter, Aviva Weinbaum, is a senior at Amherst Regional High School, and thinks about the gender pay gap a lot. She is president of the school’s Women’s Rights Club, which she has belonged to since her freshman year.

“Every week we find an article about a women’s issue that came up that week and talk about it,” Aviva Weinbaum said. “We talk a lot about representation in the media and the pay gap — that’s a huge one.”

Aviva Weinbaum, center, speaks with other members of the Amherst Regional High School Women’s Rights Club Ayla Connor-Kirshbaum, left, and Lourdes Jean-Louis.

She and her peers, through discussions, talk about women’s empowerment and also about how to change the world for their own generation.

“It is interesting. A bunch of girls who want to go into engineering and computer science learn that a male engineer makes three times as much and ask ‘Do I actually want to go into that field if I’m going to face that discrimination,’” she said. “That is something people talk about when thinking about what they are studying.”

Weinbaum wants to be a surgeon, and she knows that the field is dominated by men — only about 19 percent of surgeons in the US were female in 2015, according to the Association of Women Surgeons. She also plans to be paid the same as her male colleagues in the field.

She said while there are large social differences between the boys and girls who are her peers (girls being more mature), there is not a big difference in intelligence or ability in class. But she knows that in college and beyond that many see women as inferior, and that college can be a dangerous place for women.

“It’s a scary thing to think about that one in three women get assaulted on college campuses and most of those go unreported,” she said.

Part of how she hopes to cut into the pay gap is to educate her male peers and get more people thinking about the problem of the wage gap and women being hindered in their careers.

“If more guys know these things are sexism, they can start to change their own actions and recognize where the problems are,” she said.

Stalled in the Nonprofit World

Nikkya Hargrove, who worked in Massachusetts as part of work she did for the nonprofit organization buildOn, had a great experience doing the work of the organization, which engages students in the U.S. in community service projects and builds schools abroad.

“The work of the organization, staff, and student volunteers will be felt for years to come within the communities they serve,” she said. “I learned a great deal about the power of teamwork, commitment, and compassion while working for buildOn and serving our students.”

At the same time, however, she believes she was underpaid during her time there compared with what a man in her position would have made. Hargrove, who is African American, also thinks that taking family leave took her out of the running for a promotion.

“It is no hidden secret that wages are lower in the nonprofit sector, but that coupled with being short-staffed and being one of a few women of color in a leadership role, I feel like my salary should have been more,” she said.

Hargrove rose up in the ranks. Originally Connecticut-based, following a third promotion to program director, which included territory in Massachusetts, she was making $62,000. When she asked her supervisor for a raise, the blanket answer she received was that she was at the top of the salary range for similar work in the company.

But with the goals and responsibilities and staff she was given, she felt that another $10,000 would have been typical.

BuildOn Chief Marketing Officer Carrie Pena disagreed with Hargrove’s assessment.

“In my experience men and women are paid equitably at our organization, and some positions make more than others,” Pena said.

Pena said the organization has analyzed male-to-female ratios on some roles within the company, though not executive level. At the coordinator and manager level, men and women make within 2 percent of one another, she said.

“At buildOn we are always striving to create a diverse and equitable workplace. While there is certainly room for us to improve I personally feel thankful to work for an organization where I feel supported, as a woman, to lead and grow,” Pena said.

In the midst of Hargrove’s work, she went out on maternity leave to take care of her twins, who recently turned 2 years old. While she was out, her supervisor, who had been a woman who has had a child, left and was replaced with a man. When she returned, her new supervisor was less flexible in terms of working from home.

“It has been my experience that women who have had children and been pregnant have a tendency to go back to their own experience,” she said, adding that men she had worked with tended to be more rigid about policies following maternity leave. Men, who have not gone through the emotional roller coaster of childbearing, birth, and breastfeeding, are less apt to understand the experience of staff members who have, she said.

After taking her leave, which consisted of 12 paid weeks including all of her vacation and sick time, she found that she was out of the running for a vice president level job that had opened up in the meantime. She is not sure what the man who got the job made — but knows that the company pays upwards of $90,000 for vice president level roles.

Pena said three of the last four people who have held that vice president post have been women.

“Just because someone becomes a parent doesn’t mean they become less of a professional,” Hargrove said. “It doesn’t have to be this or that. Employers need to acknowledge the hard work of each individual and not think of the fact that they have a child.”

The Motherhood Penalty

Michelle Budig, chair of the sociology department at UMass, has done research showing that the pay gap is exacerbated when people become parents. Men are paid more while women are paid less, and often overlooked for advancement in their careers.

In a 2014 paper she wrote, called The Fatherhood Bonus and the Motherhood Penalty, Budig states that women made big gains on men in pay in the late 1970s and early 1980s moving from 63 cents on the dollar to up in the high 70s, but then stalled in the 21st century around the current level.

“Before then, if you go just through the 20th century, women would fall out of work when they got married and definitely when they had kids, and they weren’t achieving education at the same level,” she said. “There was a second wave of feminism that saw the mass entrance of married women with children. You stopped seeing women exiting the labor market after they became mothers.”

“Before then, if you go just through the 20th century, women would fall out of work when they got married and definitely when they had kids, and they weren’t achieving education at the same level,” she said. “There was a second wave of feminism that saw the mass entrance of married women with children. You stopped seeing women exiting the labor market after they became mothers.”

Where the gap has persisted, however, is when workers become parents. The pay gap becomes “activated” when men and women become fathers and mothers, Budig said.

For each child, women earned an average of 6 percent less per child that they have compared with other women. Fathers, by contrast, earn more than other men.

This is exacerbated by race and income level, Budig said. Higher-earning men got bigger pay increases when they became fathers and higher -earning women got less of a penalty when they became mothers. Minorities tended to penalized more severely than their white counterparts, her research showed.

That bias extends to those hiring for positions. As part of the study, Budig looked at the job application process and who was hired for positions. The result was that fathers were hired the most, mothers the least, and childless men and women were about equal in the middle, with childless women being hired at a slightly higher rate.

Like many others interviewed for this story, Budig put a lot of emphasis on paid maternity leave as a component to fixing the problem, and added that affordable childcare is a factor, as well. She also had an idea of how it could become politically possible.

“I think that can be sold in the U.S. as early childhood education,” she said. “I think it would be politically popular if framed as early childhood education rather than childcare.”

As for paid maternity leave, the United States is one of three nations that have no national paid maternity leave. It is an issue that affects men and women.

“Men expect to be involved with their kids; they want to be active fathers and engaged,” she said. “If they are the sole breadwinner, that’s hard to do.”

Breaking into Male-Dominant Fields

Jessa Westclark, a network specialist and a member of the professional staff union at UMass, is confident that she is paid the same as her male colleagues on her team. But she is the only woman on her team, and she worked hard to get there.

Westclark has held other jobs that are mostly male-dominated. Before she got into computers, she was a paramedic.

“I’m less easily offended than some other people might be and that might be why I don’t have some of the other issues some people might,” she said.

She pointed out that many women have trouble breaking into male-dominated fields, and that men also have trouble in female-dominated ones. Men who work in daycare or as nurses experience discrimination, she said.

And she believes it has gotten harder for women since the election of Donald Trump, she said.

“It certainly emboldened people who have a vision not of equality; they are much more open speaking out loud now,” she said. “That weighs on me, hearing it in the national conversation.”

To make change, gender norms have to be reassessed and gender preconceptions eliminated, even at the youngest level, she said.

“Girls are nice to each other and play with dolls; boys beat each other and play football,” she said. “That’s how it plays out most of the time.”

Pamela Cargill went to college at Hampshire College and studied how to design and make solar projects and managed to land a job with a local solar installation company after she graduated. But after working to help get the company profitable and acquired by a bigger solar company, she wound up getting laid off during a company reorganization years later.

Eager to try to make it in the solar industry, she moved from her home in Holyoke to California and got a job at a high profile solar firm.

But the solar industry, despite furthering the progressive cause of alternative energy sources, is still a combination of construction, tech, and finance — all heavily male-dominated fields. Cargill said many of her female coworkers wound up getting stuck in low level positions.

Working on a project for the Solar Energy Industry Association, spending hours looking for female top executives in the industry, Cargill couldn’t find more than a dozen.

“If you don’t see women at these top roles, then how can you imagine a pathway to get there,” Cargill said.

Cargill herself eventually wound up quitting from the company after seeing little way to advance.

“It was not just men and women; people of color were not well-represented and definitely not represented at the manager or above level,” she said.

Now she works for herself as a consultant. It is harder to make ends meet, but she gets to work on her own terms, she said.

The world of entrepreneurship is a difficult place for women, too, she said.

“Women are not encouraged to stand up for their value and command influence and demand value,” she said. “It is just not a trait that is reflected in pop culture and when women demonstrate those traits, there are all kinds of nasty words people roll out to describe those women.”

Dave Eisenstadter can be reached at deisen@valleyadvocate.com.