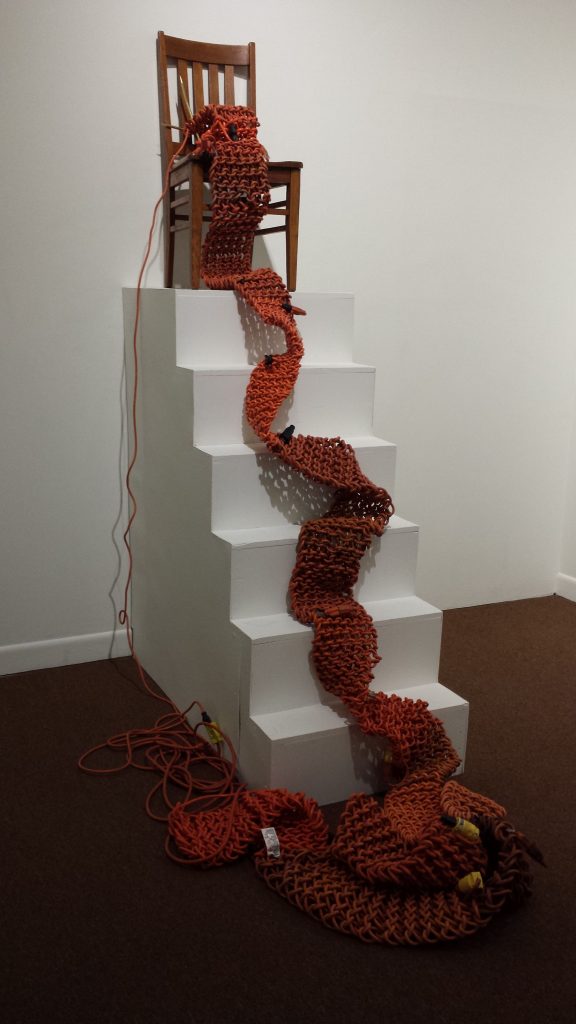

As I wait for Brattleboro artist Joan O’Beirne to arrive at her exhibit “The Scarf,” showing now through Feb. 11 at the Brattleboro Museum & Art Center, curator Mara Williams brings a museum guest into the showroom.

She gestures to the (at least) 12-foot orange weave of cables winding its way down from an elevated chair to the floor on one side of the room. Williams explains, “she knitted it entirely out of extension cords.”

Gazing at the “scarf,” made of mostly old, dirty cables, the patron raises his eyebrows, turns to Williams, and simply asks “Why?” before the pair moves to the next room.

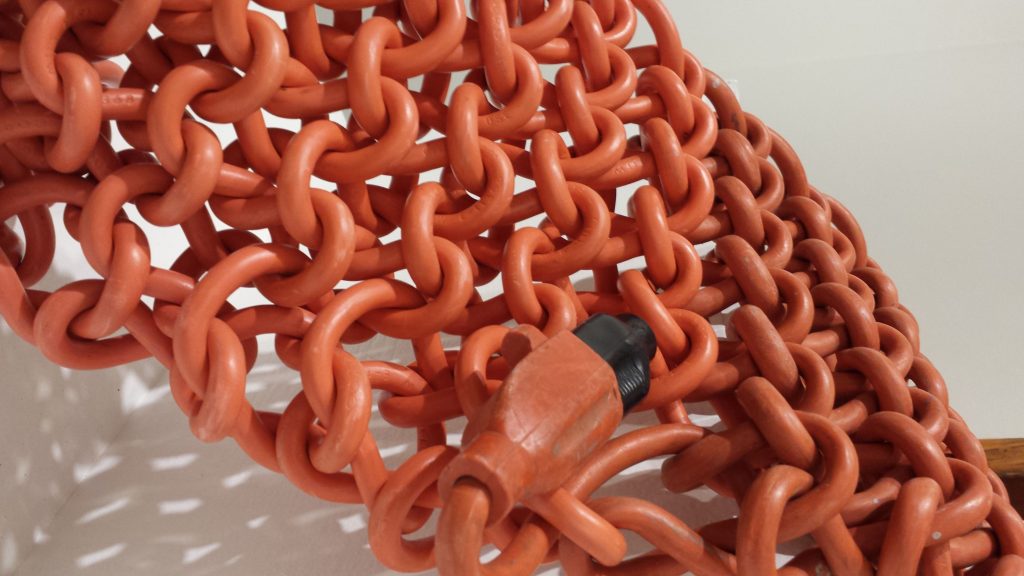

It’s a fair question. It would be hard to imagine a less suitable “yarn.” As the bent knitting needle resting in the chair attests, knitting extension cords is hard work. And the result is a scarf that won’t keep you warm and a set of dirty, blackened extension cords that extend a tiny fraction of their original lengths.

A pair of negative image, black-and-white videos playing in a different part of the room also supports this sense of fruitless struggle. Hands ceaselessly wash themselves in a bowl of water, and a close up of another pair of hands shows the arduous work of looping the thick extension cords around those same bent knitting needles — a how-to video for extension cord scarfs.

The negative space brings out the strain in the hands as they do their obsessive work — washing over and over, and bending cord around needle.

Why?

It is that question I ask O’Beirne — who is coming from her day job as photography professor at Greenfield Community College — when she arrives.

She tells me about the significance extension cords have to her: 17 years ago, her brother hung himself using one. The Scarf is dedicated to his memory.

Astonished, I ask if it is painful to be surrounded by these cords.

“Over time the pain — the sharp pain — goes away,” she says. “But you still think about it, that will always remain.”

My view of the show dramatically shifts. Here are these objects that at least at one time must have been loaded with negative emotion, woven into something new. The knitting needles in the chair show the continuous nature of the scarf. O’Beirne could keep right on knitting it if she wanted to. Just plug another cord into the last and keep on going.

Does she have a history knitting? Where did she learn?

Actually, she explains, she learned on YouTube just for this show.

“I’d never knitted before,” she says.

I take a fresh look at the scarf and the negative space videos. I’m confronted with the sad vision of a man wrapping a cord around his neck to take his life, but also the beauty of the woven work of the scarf — even with the ugly materials of old, dirty extension cords. A scarf goes around your neck, too, but provides comfort and warmth.

I see a transformation from a cold, hated, industrial object into something human and almost gentle — and the work, both physical and emotional, that went into making it.

It’s hard work, yes, but work that seems well worth doing.

While my view of the exhibit is shaped to a great degree by learning about O’Beirne’s history, no mention is made of it on the museum label that accompanies the work — except a note at the bottom dedicating the exhibit to her brother.

In some ways this may be best. O’Beirne’s exhibit is not about death. What connects the pieces is a dedication to keep going.

In fact, the night the exhibit opened, O’Beirne sat in the chair knitting the scarf as patrons came and observed.

The final piece in the show takes up an entire wall. It’s a collection of 32-inch squares of aluminum pinned to the wall like butterflies on which close-up images of another extension cord are printed.

Many of the squares — there are more than 100 — match up with adjacent squares, creating a sense of a larger picture, but many do not, doubling up parts of the image or leaving bits of cord uncompleted.

The struggle with this piece is trying to sort it all out. Somewhere in there is a really old, beat-up extension cord, wires hanging out, and pieces of duct tape hanging off it from years of quick fixes.

“A lot of my work is about struggle,” O’Beirne says. “That might be why I’m not that prolific.”

These works are definitely worth the struggle.

The Scarf is on display through Feb. 11 at the Brattleboro Museum & Art Center. Gallery is open every day except Tuesdays 11-5. Admission, $8, $6 for seniors, $4 for students, free for BMAC members and youth 18 and under. Free admission for all on Thursdays 2-5 p.m.

Dave Eisenstadter can be reached at deisen@valleyadvocate.com.