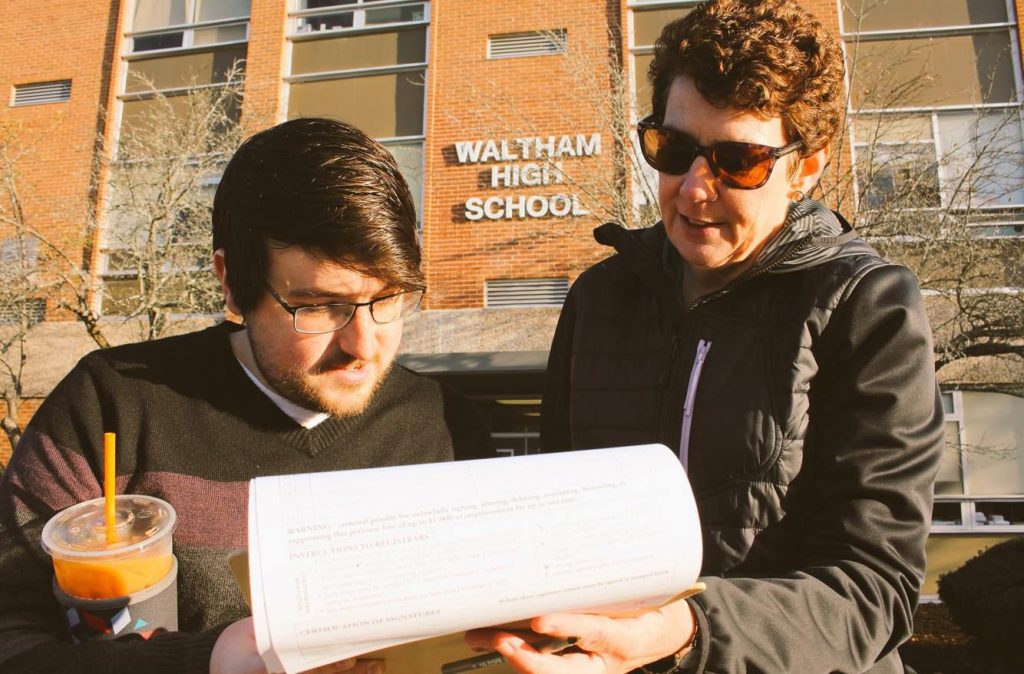

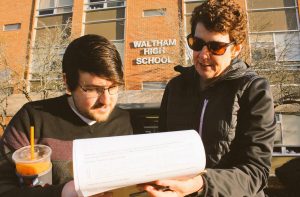

From September to the end of November, Mickey Prout, 22, a student at Westfield State University, and other volunteers would set up tables in the dining commons to talk to other students about two statewide ballot initiatives: raising the minimum wage and establishing paid medical and family leave. Stopping people during busy lunch hours to talk about politics wasn’t always easy, but Prout said that he liked the challenge and that tabling with other people is more fun than tabling alone. On their best day they might get up to 60 signatures, but on a bad day they might only get about 25.

From September to the end of November, Mickey Prout, 22, a student at Westfield State University, and other volunteers would set up tables in the dining commons to talk to other students about two statewide ballot initiatives: raising the minimum wage and establishing paid medical and family leave. Stopping people during busy lunch hours to talk about politics wasn’t always easy, but Prout said that he liked the challenge and that tabling with other people is more fun than tabling alone. On their best day they might get up to 60 signatures, but on a bad day they might only get about 25.

“So many people support it,” he said. “But it’s getting them to also fight for it.”

Prout and other activists are pursuing ballot initiatives because they don’t think the Legislature will tackle it any other way.

“The Massachusetts constitution gives the people the power to change the laws on our own,” said Andrew Farnitano, a spokesperson for Raise Up Massachusetts, a coalition that has been pushing for minimum wage increases, sick time, and paid family leave for years.

But John Scibak, House Representative of the 2nd Hampshire District, said ballot measures can make for messy laws and that legislating is best left to the Legislature.

“In general I think that ballot measures are a bad way to make policy,” Scibak said. “That person has no accountability about whether or not it works. I also respect that people have the right to express their views.”

Farnitano said waiting for the Legislature to act on its own has not produced results. In 2014, the Legislature ended up passing a minimum wage increase only after Raise Up Massachusetts filed a ballot initiative. Another Raise Up Massachusetts initiative that year, for earned sick time, wound up on the ballot and was passed by voters.

“Neither would have happened without our grassroots coalition and signature collection,” Farnitano said.

Now with thousands of certified signatures, activists are pushing for up to eight initiatives that may end up as ballot questions in November. They including a $15 minimum wage, paid family leave, a new tax on high earners, and an attempt to rescind previously passed rights for transgender individuals.

For activists organizing around the minimum wage increase, 2018 could be a turning point in Massachusetts.

“We’re stronger together,” said Betzaida Ventura, a minimum wage worker and activist from Holyoke. “I’m so proud that we continue to fight, but it’s not over. We need to fight for our kids.”

On The Ballot: Trans Protections

Two measures are already on the 2018 ballot: a veto referendum to try and repeal a transgender anti-discrimination law and a constitutional amendment to raise the income taxes for wealthiest earners.

A veto referendum, which is a push to undo a law previously passed by the Legislature, does not require as many signatures as other types of ballot initiatives to be certified, but it has to be submitted to the Secretary of State within 90 days of when the law was signed by the Governor. The original transgender anti-discrimination law, which protects people from being discriminated against in public places based on gender identity, was signed in July of 2016. The veto referendum was certified last year.

The group that submitted the veto referendum, called Keep MA Safe, argues on their website that the original law could negatively impact the safety of women and children.

After several attempts Keep MA Safe could not be reached for comment.

William Harron, 28, of Boston, is member of The Crossing church and phone banked with his congregation this August against the veto referendum. Harron said that he doesn’t like talking to people on the phone, but that he felt supported by his church community and was motivated by the church’s role as a transgender ally.

“The work of justice is important to my own faith,” Harron said. “(We are) giving people information against the fear-mongering campaigns that are ramping up.”

National trends and anecdotal local information indicates that transgender individuals are far more likely to be victims than attackers. According to the Springfield Police Department, there have been no assaults in public restrooms since the original law passed. Police said that there has been one assault and battery charge in that time that was reported to be anti-transgender. This reflects national trends, including a UCLA study of Washington, D.C., that found that 9 percent of transgender individuals in that city were physically assaulted and 46 percent were verbally harassed in 2015.

Kayden Moore, 29, of Northampton is transgender and said that his gut reaction to the veto referendum was anger.

“I want to look someone in the face who has this issue with me and my friends existing,” Moore said.

He said that it is disheartening to see his civil rights and liberties up for debate, whether or not the law is repealed come November. He said that, while he feels lucky to live in Massachusetts, having those protections challenged all over the country changes how safe he feels state-to-state.

“It’s on the back of my mind and on the back of a lot of trans people’s minds when they leave home,” Moore said.

The original bill overwhelmingly passed the House (116-36) and Senate (33-4) and had broad support from law enforcement across the state. The Massachusetts Chiefs of Police Association and Massachusetts Major City Chiefs and 19 other local law enforcement officials joined the Massachusetts Freedom for All coalition that campaigned for the original bill and against the current repeal attempt.

One confusing aspect is that a “yes” vote is a vote against the repeal effort. On the ballot, the question will read “Do you approve of a law summarized below …” So a “yes” vote supports the original law that prohibits against discriminating against people based on gender identity and a “no” vote supports repealing that law and removing protections against discrimination based on gender identity.

“We are gearing up,” said Matt Wilder, spokesperson for Freedom for All Massachusetts. “We’re not taking anything for granted. We have to get our message out and lift up the voices of trans people.”

On The Ballot: Taxing High Earners

The other initiative already on the ballot is a constitutional amendment, which — like veto referendums — have a different path to the ballot than most of the other initiatives. As a constitutional amendment, the Income Tax for Education and Transportation Amendment, also known as the “Fair Share Amendment,” was required to go through two successive Legislative sessions (so signatures were gathered in 2015).

The measure would institute a 4 percent tax on all income earned above $1 million per year to be used for education and transportation.

Prout, the student organizer at Westfield State, is a graduate of Springfield Technical Community College who also organized with Raise Up Massachusetts on the Fair Share Amendment. Prout was motivated to organize for this initiative because of his student debt. He currently owes $13,000 in student debt and still has three to four semesters to go. He expects to owe $20,000 to $25,000 by the time he graduates.

“There are ways for education to be more affordable,” Prout said. “We could actually get free college and earn the education that we deserve in a fashion that doesn’t put us into debt for the rest of our lives.”

The revenue from the tax can then only be used for public education, public colleges, and universities and the repair and maintenance of roads, bridges, and public transportation, subject to appropriation by the state Legislature.

“It’s a commitment to building an economy that works for all of us, not just for a few,” said Andrew Farnitano, a spokesperson for Raise Up Massachusetts. “(We’re) investing in education and transportation that are both tied to letting people get ahead.”

As the Chairperson of the Joint Committee on Higher Education, Representative Scibak supports there being more money for public education and said that the tax could raise between $1.6 and 2.2 billion. However, he said that what concerns him is that the ballot question doesn’t specify how the education money will be spent, so there is no guarantee that it will go towards higher education.

He also noted that the state could lose $1.3 billion if another proposed ballot question to decrease the Massachusetts Sales Tax was voted through.

Making Initiatives Into Ballot Questions

The other six possible ballot questions are an initiative to create a citizens commission to regulate campaign finance, two versions of a petition to institute patient limits for nurses, a sales tax decrease and tax free weekend initiative, an initiative for a minimum wage increase, and a paid family and medical leave initiative. All of them are headed to the Legislature as what are known as initiative petitions.

Any Massachusetts citizen can create an initiative petition with 10 signatures and a submission to the Attorney General, but there are several hurdles to overcome before a measure gets placed on a ballot.

Two of those initiative petitions are Raise Up Massachusetts campaigns: one to raise the minimum wage to $15 an hour and one to establish family and medical leave.

“(The ballot question) is an important tool to put our issues at the top of the legislative agenda,” Farnitano said.

The first step to the ballot is to submit the initiative petition with 10 citizen signatures to the Attorney General’s office. If the Attorney General certifies the initiative petition, it’s then filed with the Secretary of State and the petitioners have about two months to gather thousands of signatures in support of their petition (3 percent of votes cast in the last gubernatorial election is the required to move forward, which was 64,750 signatures this year).

Raise Up Massachusetts gathered 274,652 total signatures this fall for its two initiatives (174,376 of which were ultimately certified) and said that they received signatures from 346 of the 351 communities in Massachusetts.

This fall more than 20 different initiative petitions were certified, but only six measures had the required number of signatures and are going to be considered by the state Legislature once the new session starts in January. For each of the six ballot initiatives, the Legislature has until mid-May to either approve the measure, reject it, propose a substitute, or do nothing, according to Scibak. He said that given the contentious nature of the ballot questions, he does not expect the $15 minimum wage initiative, or any of the initiatives, to have enough votes to pass the Legislature by May.

Even though Representative Scibak supports the minimum wage, paid family and medical leave, and “Fair Share Amendment” initiatives, he knows that if they are passed there will be many details to iron out afterwards in order to make the initiatives effective.

“(Ballot questions) provide an opportunity to get something through in another fashion,” Scibak said. “The unfortunate thing is that once that person walks out of the voting booth, they don’t have to deal with the repercussions.”

There are a few examples of successful ballot initiatives from recent elections. The ballot question in 2016 to legalize recreational marijuana in Massachusetts was a big win for marijuana activists, but Scibak noted that many of the details necessary to implement the law had to be written after the fact.

“The millions of people who vote on a particular ballot question don’t have to pick up the pieces, intentional or unintentional,” Scibak said, adding that ballot questions are often complicated and difficult to understand.

If the ballot questions are not enacted, petitioners will have until early July to gather signatures equal to 1/2 of a percent of the number of voters in the most recent gubernatorial election — a little less than 11,000. If enough signatures are gathered, the measure and any legislative substitute will be placed on the ballot.

Still In The Works: Minimum Wage

For labor activists, 2018 could be the year they get a measure for a $15 minimum wage before Massachusetts voters, which would mean the state would join California and New York, which have already passed $15 minimum wage legislation.

Ventura, the activist from Holyoke, is a Personal Care Attendant (PCA) who makes minimum wage and is a union leader in 1199 SEIU.

“Cost of living is so high,” Ventura said. “There have been times where I either need to pay my bills or put food on my table.”

Ventura gathered signatures for the minimum wage initiative and for paid family and medical leave all over Holyoke, from Stop & Shop to outside of the Holyoke Medical Center. Ventura is fighting for higher wages as a PCA. She said the work she does is necessary for her clients, who are mostly elderly people who want to continue to live in their homes.

Ventura said that she has patients who would not eat if she was not able to come to work and who could get sick from her if she was forced to come to work sick due to financial pressure.

“I have such a passion for the elderly,” Ventura said. “I’m going to continue to fight for their safety and for their dignity.”

The $15 minimum wage initiative would raise the minimum wage by one dollar per year beginning in 2019 until it reached $15 an hour in 2022. After that, wages would be increased based on increases in the Consumer Price Index. The initiative would also raise the minimum wage for tipped employees from $3.75 an hour to $9 an hour, which would be a very significant increase for the restaurant and bar industry.

Mona Shadi, 33, of Northampton, is a service worker who works multiple jobs to make ends meet.

“I think $15 an hour is great, but with inflation and the cost of living no matter how much it goes up you’re still in this monthly rat race,” Shadi said.

For Shadi, the “monthly rat race” prevents her from saving for other long term goals, like a mortgage, a savings account, or going back to school. Shadi is currently thinking about getting her associate’s degree in a different field, but she has been a service worker for so long that she said that she hasn’t had time to think about the future.

“My experience hasn’t been ‘what do I want to do?’” Shadi said. “It’s ‘I can do that job.’ I work to survive.”

While many food service and retail workers would be affected by the minimum wage increase, they are not the only ones. Erin Wilson is a servicing representative for UAW local 2322 who said that the narrative that all minimum wage workers are teenagers is a myth. A report released by the Massachusetts Budget and Policy Center last week showed that teens only represent 10 percent of the workforce who would benefit from the minimum wage increase. Her local represents many different kinds of workplaces, including many in the mental health and behavioral health fields.

“The state just does not fund mental health the way they should,” Wilson said. “It doesn’t reflect a minimum wage and it doesn’t reflect the quality of work they’re doing.”

Wilson said that workers in those fields, like Ventura, often work long hours and may be asked to perform care work that is equivalent to that of a nurse, including medical care, medical administration, hygiene, transportation, therapeutic intervention, and coordinating with care providers.

Associated Industries of Massachusetts (AIM) is a general employer association that represents about 4,000 employers in Massachusetts. According to Executive Vice President of AIM Chris Geehern, the employers they represent have an average of 50 employees and about three quarters of them would be affected by the proposed minimum wage increase.

“You can change the minimum wage, but ultimately there are better ways to advance people and to help them make a better living,” Geehern said.

Geehern said that AIM would rather support legislation and ideas that encourage educational or training opportunities for low wage workers.

“Ultimately the company pays workers the value that workers provide the enterprise,” Geehern said. “It’s not a personal decision, it’s an economic one.”

Moore, the transgender activist from Northampton, is a cafe manager whose experience in the restaurant industry has shown him that while there may be consequences to raising the minimum wage, it’s a necessary change.

“On the whole I think it’s a great thing,” Moore said, “but I think it’s going to be very hard for independent restaurants to do well because they operate on thin margins already.”

Moore said that higher wages will help even out the imbalance in pay between the front of house and the back of house, but that it may also result in higher priced products.

Some business owners in the Pioneer Valley and beyond support the minimum wage increase and have already started to make adjustments internally to afford the added cost.

At Real Pickles in Greenfield, Founder and General Manager Dan Rosenberg said that their starting wage is currently around $13 an hour. To get there, the management team met a few years ago to reassess their wages and benefits and decided to make a plan to steadily increase both. He said that they have plans to reach $15 an hour, but that they would welcome to push from the state.

“It’s about the moral compass,” Rosenberg said. “People need to get paid a livable wage.”

Still In The Works: Paid Family And Medical Leave

Even though workers can now accumulate up to 40 hours of sick time a year in Massachusetts, that may not be enough time for workers to recover from an illness or bond with a new child.

“People have to go back to work before they’re able and ready because they can’t afford (to go unpaid),” Wilson said.

The paid family and medical leave ballot initiative would establish a trust that employers pay into to provide employees with 16 weeks of paid family leave and 26 weeks of paid medical leave. During that time employees could receive 90 percent of their pay rate, up to a maximum of $1000 per week.

Representative Scibak said that the paid family and medical leave initiative makes sense for small business owners who want to retain employees without having to pay double to replace them while they are away.

“Small businesses want to do the right thing and take care of their employees, but right now it’s unaffordable,” Farnitano from Raise Up Massachusetts said.

For Geehern, one of the consequences of the paid family and medical leave on the businesses that AIM represents is the cost. A study released by UMass Boston last month compares the ballot initiative to two bills in the House and Senate that also address paid family and medical leave and the ballot initiative is estimated to be the most expensive, costing about $950 million dollars a year, which would be split by employers and employees in Massachusetts.

“For us, creating a new centralized, bureaucratic expense is a burden on employers’ ability to grow,” Geehern said.

For Rosenberg, the Real Pickles general manager, paying for wage and benefit increases involves continuing to grow as a company and carefully increasing prices over time, but he said that it’s worth it for worker retention and satisfaction.

“As we’ve grown our wage and benefits we’ve seen higher job satisfaction,” he said. “Staff feel better treated, they’re doing more high quality work, and they feel more invested in their work.”

Meg Bantle can be reached at mbantle@valleyadvocate.com.