It Begins in October 2017

All 18 of us in Leverett are excited and maybe a little nervous. We live in a small town — Leverett: population, less than 2000 — in western Massachusetts. The Kentuckians are coming to us — 15 of them, men and women, young and not-so-young, from Letcher County in Eastern Kentucky: coal country. They’re coming in two vans to meet us, to be hosted by members of the Bridging Group of the Leverett Alliance. Thirteen hours of driving for them to meet us and for us to meet them, to spend a long weekend together, to talk — especially about what joins us.

They must be even more nervous than we are. They have stereotypes of us; we have stereotypes of them. We have read many books to prepare us — our favorite: Night Comes to the Cumberlands, about the economic history of Appalachia. We’ve screened films about the region as well.

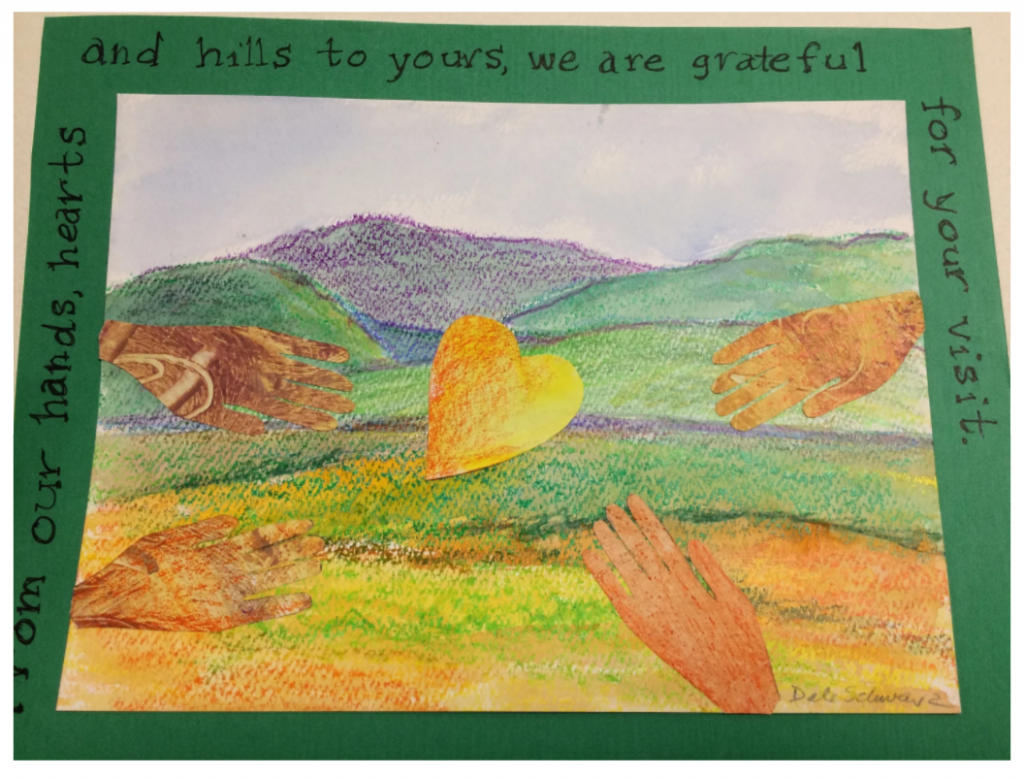

We call our project “Hands Across the Hills.”

People from Leverett and Letcher County, Kentucky, speak in one of three dialogues in October, 2017. Chana Rose Rabinowitz photo

Since the 2016 elections we’ve kept hearing how split America is. In Letcher County, Kentucky, over 80 percent voted for Donald Trump; in our town 88 percent of us voted for Hillary Clinton. Red states, blue states. During the run-up to the election I never met a single Trump supporter. When Trump won, people in our town weren’t just disappointed; they grieved, and some wept. In Letcher County, Kentucky, they celebrated. They shot off guns!

Us/them. . . Red states, blue states — like football uniforms. Like armies: a civil war.

Are we one country or are we, at the very least, two? Is there a divide and can we bridge it? Can we come to understand one another? Does it matter if we do or don’t share understanding?

How did we find people from what seems a different America to engage with us in dialogue?

One of us read an article by Ben Fink, an organizer in Eastern Kentucky for a culture hub called Appalshop, which trains residents in Appalachia to produce films and other works about the region. Since 1969, Appalshop has been a home for cultural expression in Appalachia, “celebrating the culture and voicing the concerns of people living in Appalachia and rural America.” Ben’s article asked for partners in dialogue. “Want to work with us? Let’s talk.”

We talked. We began to work together to create a plan to meet.

Our Hands Across the Hills group is led by Paula Green, who co-founded the Leverett Peace Commission, instrumental in organizing the Leverett Alliance after the 2016 election, which upset and angered so many in our town. She has led peace-building and reconciliation work in dozens of countries. Green sees the Leverett/Kentucky project as a model that can be replicated all over America.

“There’s a big YES for this project,” she says. “Everyone who hears about it likes it. It’s a symbol of hope at a time of despair. People say, ‘There’s nothing we can do.’ Well, here’s something we can do!” It’s not only individuals meeting individuals; it’s people from very different backgrounds with very different ideas listening to each other, learning from each other and applying what they learn to other contexts, to other groups who have been stereotyped and blamed.

Before the Kentuckians come, we plan and plan — to develop a structure of activities and dialogue for the weekend, to raise funds, to make contact with media, to match our guests with members of our group for home-stays. Meetings, volunteering, emailing, writing press releases, talking on the phone. And importantly we train: how do we speak to our visitors? What questions do we avoid?

We’re 18 busy people.

And Then, At the End of October, the Kentuckians Come

The Kentuckians arrived late Thursday night at Leverett Town Hall, and were shepherded to the homes of their hosts. Next morning songwriter Sarah Pirtle strummed her guitar and led us in the song she wrote for us. In early afternoon we plunged into an art project about our families and their history.

Then came our first main event: our first facilitated dialogue — two and a half hours in a circle — about family.

Common to all of us was deep love of family; common to all of us was a heritage of oppression. Kentuckians were oppressed by coal companies and had family memories of deprivation, sickness, and death. Some from Leverett had family memories of persecution in Europe — relatives murdered who couldn’t flee. It’s interesting that half of the Leverett group and the leader of the Kentuckians are Jews, children or grandchildren of immigrants seeking refuge. These family memories of escaping Europe were surprising and powerful for the Kentuckians as they were for us. The memories redefined the meaning of “immigrant.”

I told the story of my Jewish grandmother letting her sick neighbor borrow her passport while she herself hiked with a guide over the Carpathian Mountains into Romania, where she retrieved her passport and rejoined her family. Those who stayed in Moldova were wiped out in the First World War and in the Holocaust.

While telling a story about her family’s survival, one woman from Leverett started to cry. Most of her family was murdered in the Holocaust. Later, a woman from Letcher County said she’d always been afraid of immigrants and refugees but had never met one. Now that she had, she believed she would never close her heart again. We’d all “known” what families have gone through, but hadn’t known with the heart: the commonality of injustice and suffering.

We didn’t speak about politics, not all afternoon. As far as I can remember, the T name was never bruited. Watch out, I said to myself. As we grow more comfortable the divisions will appear. But by the end of the afternoon, for me, at least, a kind of magic had occurred: the Kentuckians had become transformed. It was as if I’d re-invented, reimagined, the people I’d met earlier. Instead of being strangers I was respectful toward, they became colleagues, fellow workers. They didn’t even look like the people I’d met earlier. The differences that we were going to bridge — well, where were they? We felt like a single group. A search for agreement? That seemed artificial. We were connected more powerfully — sorry if this sounds simplistic — at the heart.

But was this connection at the heart enough?

Going Public

All along, our intention was to share our endeavor with the Pioneer Valley and we created a program for that Saturday morning at the Leverett Elementary School. This included presentations by our guests about Letcher County and from Leverett about our small town, singing by the Leverett Community Chorus and a chance for the public to talk with our Kentucky visitors over potluck lunch in the school cafeteria.

Nearly 300 people showed up for a public event to meet the visitors from Kentucky at the Leverett Elementary School. Kip Fonch photo.

We had no idea how many people would come to meet the Kentuckians. Fifty? A hundred? We photocopied 150 programs, which was well over what we thought we’d need.

We set up folding chairs, which quickly filled up. Then found more folding chairs, and those filled up. Finally we set up all the chairs we could find, and still many had to stand. There were almost 300 people in the gym. Everyone — we, the Kentuckians, even the audience itself could hardly believe this huge turnout on a bright autumn day. A chord was struck … we hardly knew what to call it.

We learned much that morning. Our guests spoke with passion and honesty, and the audience listened. The Kentuckians had to cope with the mines and the closing of the mines, with terrible poverty and the destruction of the land. Similarly, our part of Massachusetts had to cope with the many mills and the closing of the mills, with tobacco growing and the diminishment of tobacco. But Leverett and the Valley were fortunate — we had new life given us by the growth of four colleges and a university. Nothing in Letcher County has replaced coal.

I think the most powerful moment that morning belonged to Gwen Johnson of Kentucky, whose uncles and father died in mining accidents. “When the coal business began to crumble, I knew we were going to take a bad hit,” she said, “because trash collection, senior centers, and other county services are paid for by coal severance tax. They shut down our senior citizens centers… they pulled all the dumpsters from across the county, so there’s no place to bring our debris. . . I’m thinking, ‘Oh my god, what are we going to do?’” When she voted in the last election, she didn’t like her choices — felt dirtied coming out of the voting booth — but couldn’t desert her people.

When we gathered for a feast of potluck lunch, the Kentuckians were literally mobbed by Valley residents eager to talk with them. One Kentuckian exclaimed, there was a lot of unexpected love in the school that morning!

An Explosive Moment

That afternoon, we held our second closed dialog, and Gwen once again took the floor. She said that when she sees a loaded coal truck or a coal train passing by, she’s happy. Happy for the jobs. Coal, she said, might make a comeback — it was needed, wasn’t it, when there was a war. At other times the need dropped away, and mining dropped away. Herby Smith, a filmmaker from Appalshop, reminded us that jobs in mining demanded courage and gave dignity, camaraderie, and a reasonable wage. “Miners do something real; they make something.”

Yet they also spoke of the dangers and exhaustion of mining work.

The contradictions were evident.

Now our dialogue facilitator Paula Green deepened our discussion. She said it made her very sad to hear that at a time when coal mining was becoming less profitable and was intensifying climate change, the only option the people from Letcher County could imagine was work in coal mining, oppressive work that poisoned the water, destroyed the land, and killed miners — slowly with black lung or all at once in an accident. War? Are we willing to have a war in order to bring back jobs? Is coal really the only option people can imagine?

It was an explosive moment. We had looked to Paula, a peace-builder, to help us through what we thought might be difficult conversations, and here she was attacking coal in front of our Kentucky guests. I was sure that now gloves would be off, and we’d get down to painful, difficult talk.

But people spoke to each other with honesty and respect. We spoke the truth of our experience. Truth balanced against truth. Yes, the people from Letcher County acknowledged, they were exploited, were oppressed. We’ve read about the company stores, about wages given to the miners only in scrip. I owe my soul to the company store. Yes, coal is less economically viable than it was. But it’s all they have.

We understood the felt need of people in Kentucky to support their people. On the one side, someone said, her left hand cupped, was the long-term possibility of destructive climate change; on the other, her right hand cupped, the immediate need to pay for food and rent. How, she asked, could they vote for someone who said she was going to “put a lot of coal miners and coal companies out of business”?

Of course, Hillary Clinton said what she said about mining in a context: she wanted to create other jobs — better jobs, green energy jobs — in Appalachia. But all that Kentuckians heard — heard over and over on TV — was her single sentence: she was going to get rid of coal, get rid of mining jobs.

And what other jobs were available now? Minimum wage jobs at MacDonald’s? It’s easy to be a liberal here in Leverett. If we, in Leverett, needed jobs in coal in order to put food on the table, our priorities might be different.

On Saturday evening we brought food for potluck to the basement of the Montague Common Hall and contra danced upstairs. More than a hundred people came to eat, dance, and participate in shape-note singing. Communal physical activity, fun, was a welcome break from the intensity of the dialogue that afternoon.

A Wall Removed, and Another Journey to Make

During the third and final session of dialogue on Sunday, I realized that somehow we’d changed. We were hardly “other” to each other. We’d gotten past political agreement and disagreement, past issues of class, of stereotypes. We’d done so, it seemed, not by avoiding hot-button topics but by seeing one another surprisingly deeply — seeing one another as individuals, not only as representatives of a culture, of a social group. We listened to each other. We weren’t debating.

Monday at dawn after a windstorm the Kentuckians left, with gifts we gave them, with snacks for the road.

I feel we’ve already made some political change and created a model for change. For years we’ve been suckered in. “Enemies” — who aren’t rightfully enemies — have been created in America. To divide us into enemy camps, to encourage us to have contempt for one another, serves the interests of some powerful people very well. Personal change is fundamental to deep political change. If we can export the process we’re going through, export it all over America, we’ll have begun to make a new nation. We may continue to have different political positions, but we won’t fear and despise each other, won’t stereotype, caricature each other. Generosity, openness, love — these are not only attributes of personal relations; they define, we hope, the basis for a new politics.

Paula Green put it this way: “We’re seeing the face of the other, and that’s where change happens.”

Here in the Pioneer Valley so many folks contacted Hands Across the Hills to find out how our entire October weekend turned out that we held another public event in December. Over 120 people came to hear our experiences and reflections and to ask us questions. So many expressed interest in learning how to facilitate bridging dialogues that Hands Across the Hills is sponsoring a three-session training series with Paula Green in January, which immediately filled with 30 participants.

Hands Across the Hills is planning our late April trip to Whitesburg, Kentucky, with hope in our hearts as we meet more Kentucky folks and learn about their lives. What will we find when we make our reciprocal visit? We will be welcomed by the Kentuckians whom we know … but what about others in Letcher County? We will carry the hopes of the Pioneer Valley with us. We all look for hope, for action to overcome despair, for connection with fellow Americans.

John J. Clayton, Professor Emeritus from the English Department at UMass, has written many novels and collections of short stories, and books of criticism on modern fiction. He lives in Leverett.