Despite the legalization of recreational cannabis use for adults in Massachusetts over a year ago, there is still no standard of measure or device to test people behind the wheel for marijuana intoxication. This presents a problem for law enforcement officers who don’t have the equivalent of a breathalyzer and the .08 blood alcohol content standard for cannabis use, and also for people who are concerned that they may be impaired and unsure if they should drive.

In response to this issue, Professor Michael Milburn, a professor of psychology at the University of Massachusetts Boston for almost 40 years, created and funded an app called DRUID (DRiving Under the Influence of Drugs) to help users to assess their own levels of impairment and potentially help law enforcement officers and employers test impairment as well.

“‘I think I’m okay,’ in the pre-DRUID era was the best you could do,” said Milburn.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports that drugs and alcohol interfere with the brain’s ability to function properly. Driving while impaired by any substance is dangerous.

“You can’t really assess your own level of impairment,” Milburn said. “The app is perfect for that.”

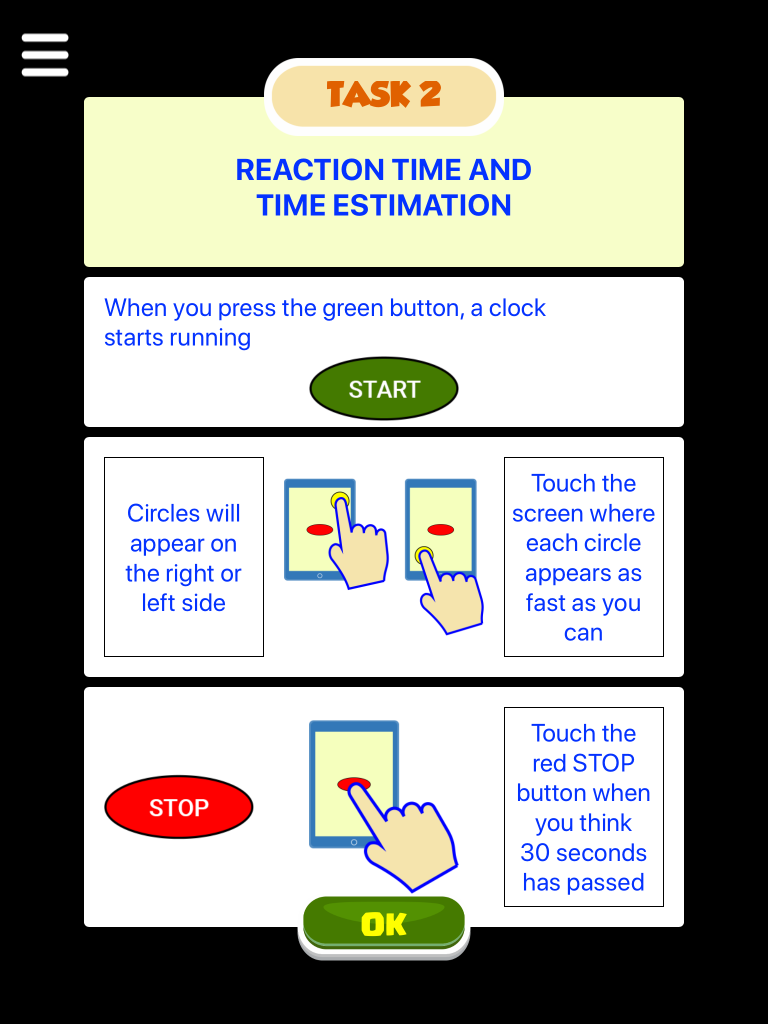

DRUID, which can be downloaded by iPhone and Android users for $0.99, consists of a series of tests that Milburn chose based on driving impairment literature. Users have five minutes to complete four tests that test for reaction time, divided attention, decision making, and balance. Milburn said that the app is best used by establishing a personal baseline by completing the tests once a day.

“Start your day with DRUID,” Milburn said is one of the app’s taglines.

According to the CDC, marijuana can slow reaction time and one’s ability to make decisions in addition to impairing coordination and distorting perception, which are all important aspects of driving. The problem is that there is no accurate roadside test for THC (Tetrahydrocannabinol) levels in the body.

In July of last year, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) published a report for Congress on marijuana-impaired driving that described the current process for assessing if someone is driving under the influence of cannabis. If a law enforcement officer stops a driver for inappropriate driving and then suspects that the driver is impaired, the officer can perform a Standardized Field Sobriety Test and test a breath sample for blood alcohol content. If the driver’s BAC test doesn’t match up with the observed level of impairment, the officer can ask a Drug Recognition Expert to help evaluate the suspect or ask for a sample to be analyzed by a toxicology lab.

Despite those tests, there is no universally accepted limit of THC in blood for operating a motor vehicle. In Colorado and Washington there is a legal limit of five nanograms of active THC in the blood for drivers, but because THC is fat soluble that measure may not be an accurate way to test impairment, Milburn said. The NHTSA report concludes that there is no clear correspondence between the THC levels in the blood of an individual, the performance of that individual when compared to a baseline, or that person’s subjective feeling of being high.

According to Northampton Chief of Police Jody Kasper, the Northampton police department has three drug recognition experts (DRE) on staff. She said if a DRE is asked to examine an operator who is thought to be under the influence of drugs, they do a much more medical analysis of the person than a Standard Field Sobriety Test, including examining pupils and taking a pulse and blood pressure. Those tests usually occur back at the station after the officer on scene has determined that the driver is impaired based on other evidence.

“It’s in combination with your impaired behavior,” Kasper said. “We have to show that the operator was impaired.”

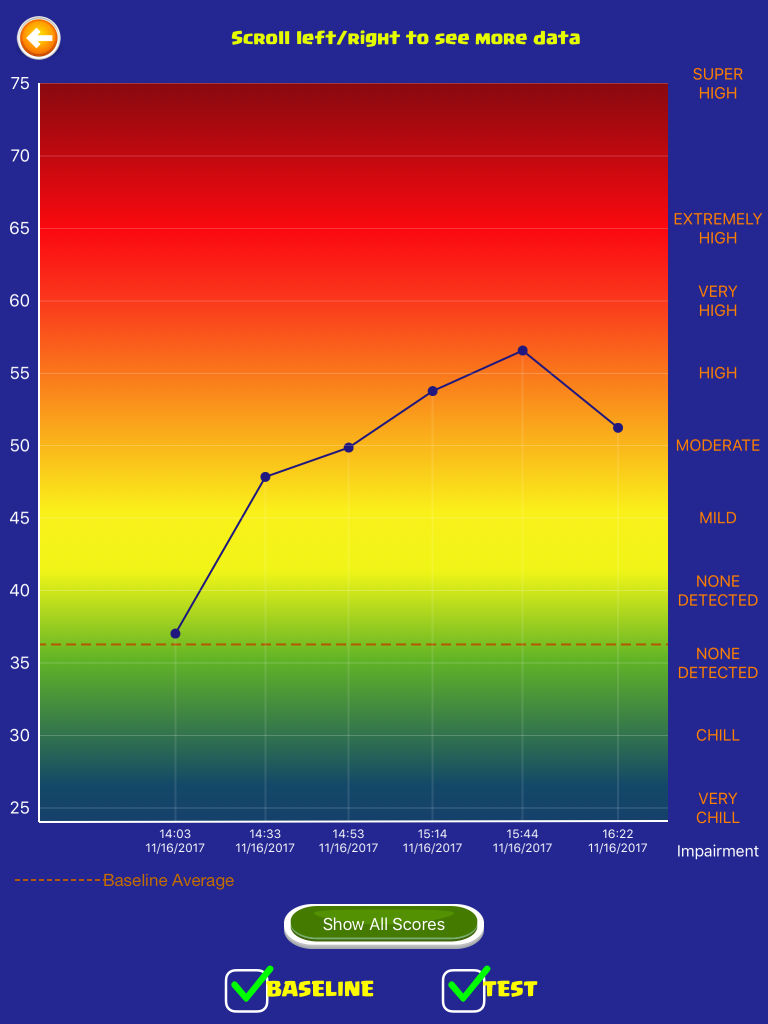

This is why Milburn feels like his app is so important in 2018, because it can test for impairment not just THC levels. While he does not know if law enforcement officers will ever use DRUID, it can at the very least help individuals to test themselves before driving impaired or getting in a car with an impaired driver. According to preliminary data, a score of 55-58 on the DRUID app is the average level of impairment for someone with a blood alcohol level of .08, so anything above 55 is impaired. Milburn did mention that the tests take a little getting used to, so it is not uncommon for initial scores to be at an “impaired” level.

“DRUID is a tool, and like any other tool you have to practice with it in order to use it effectively,” Milburn said.

Milburn said that DRUID’s potential applications are seemingly endless. Employers could use the app to test people who use complicated and dangerous machinery at work, the military could use the app to prevent accidents due to exhaustion, and the transportation industry could use the app to let drivers know when they need a break.

“I want to stop impaired people from getting on the road in the first place,” Milburn said. “And build responsible drug use.”