The nondescript building in which Anchor House of Artists is located is misleading. It’s exterior is plain and white, sitting on the very edge of Pleasant Street seconds from the highway. There is no extra signage to alert visitors that they have, indeed, arrived. And there is no indication that the galleries and studio work spaces inside are literally warehouses of paintings and sculptures. Once inside, you are surrounded by color, form, and curiosities. Never judge a book by its cover.

Anchor House is a gallery for “artists with mental illnesses,” says founding director Michael Tillyer. When asked if he would consider it a venue for “outsider art,” he immediately rejects the term. “I struggle with that; it suggests a genre, but all of these artists can’t be heaped under one umbrella. They all have different styles.” Following the mission to “subsidize and represent the interests of artists living with mental illness,” Anchor House is hosting photographs by Granby native Dylan Donahue. Donahue’s exhibit Cost of Contentment is an unvarnished glimpse into addiction and the tiny world in which Donahue is held captive by his addiction. His photographs are an unrelenting excursion into the bleak twilight world in which addicts are confined and a crude documentation of the often-present dual diagnosis of mental illness.

Anchor House is a gallery for “artists with mental illnesses,” says founding director Michael Tillyer. When asked if he would consider it a venue for “outsider art,” he immediately rejects the term. “I struggle with that; it suggests a genre, but all of these artists can’t be heaped under one umbrella. They all have different styles.” Following the mission to “subsidize and represent the interests of artists living with mental illness,” Anchor House is hosting photographs by Granby native Dylan Donahue. Donahue’s exhibit Cost of Contentment is an unvarnished glimpse into addiction and the tiny world in which Donahue is held captive by his addiction. His photographs are an unrelenting excursion into the bleak twilight world in which addicts are confined and a crude documentation of the often-present dual diagnosis of mental illness.

Donahue’s exhibit is installed in Anchor House’s first gallery. It is a stark and dark space better suited for office furniture, but it’s a good fit for Donahue’s collection. His photographs are taken with an iPhone; the images blown up to 16 by 20 and other standard sizes. They are not framed, but rather tacked up haphazardly by magnetic nails. The bottom of the photos are not secured at all, and, thus, they lurch forward before curling backward again so the bottoms edges glance the walls. “He had a vision of how this was to be hung,” Tillyer assures. “The work is hung so rawly, it’s viscerally connected to his recovery. These prints … are a part of his recovery, a part of his healing but it’s not art therapy.” Tillyer says the words “art therapy” with a modicum of contempt, as if they further stigmatize mental illness and degrade the work produced by his artists. It’s understandable; he has dedicated 20 years of his life creating a space where people like Dylan Donahue can share their art, and he shows no signs of slowing down.

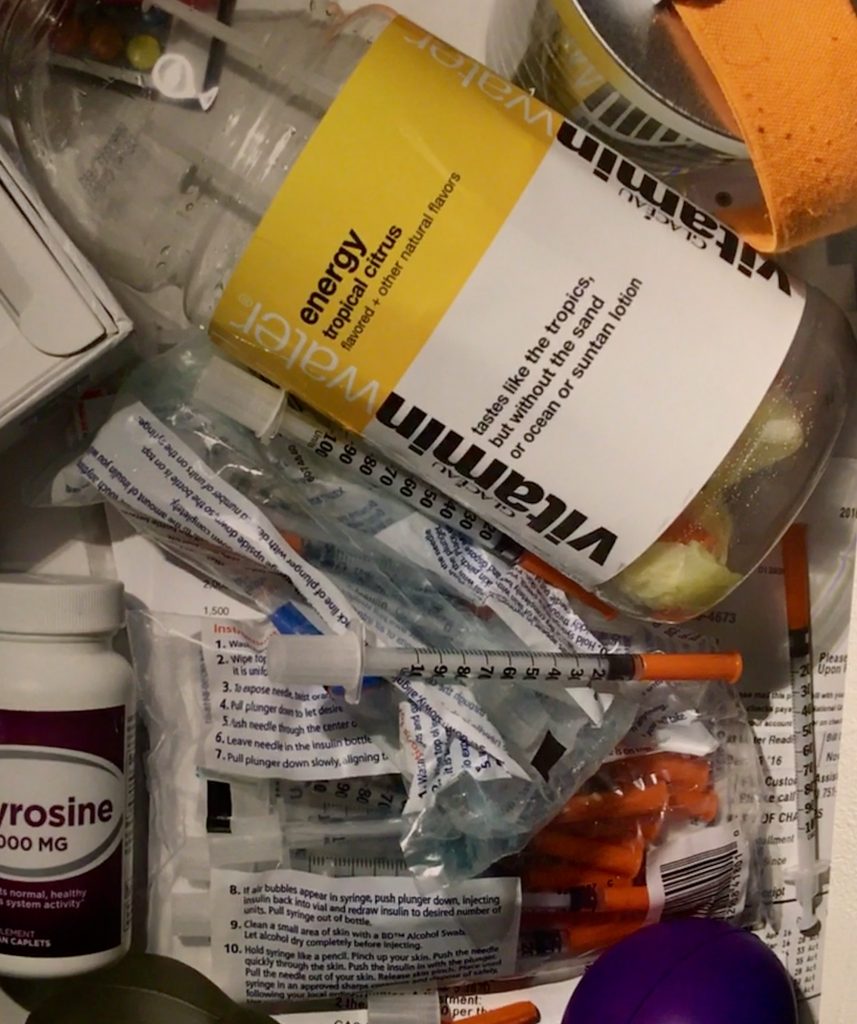

The installation feels and looks unfinished and even puerile, and if Tillyer is not present to confirm Donahue’s modus operandi, the viewer has no idea whether it is purposeful or just the result of inexperience. There are no title cards to describe his works and no artist biography. There is only a price list on which the cost of the print corresponds to its size. It, too, is tacked haphazardly to the wall. But even without title cards, most of the images lack mystery. Donahue’s subjects include empty and full syringes, powdered substances, spoons, a ghostly white arm marred by track marks and injection sight bruises, and a man injecting drugs. There is nothing beautiful in this collection of photographs; nothing for the eye to linger upon, no feeling of having been made better by the experience. Rather, it is a visual companion to the myriad stories of loss and heartache that are so familiar as communities across the country wrestle with the implacable opioid epidemic.

All of Donahue’s images are in full color. Ranging from a portrait of a man nodding out to a few failed attempts at capturing the beauty of a cluster of red roses and babies breath. But two photographs, in particular, crystallize the chaos of not only Donahue’s installation but the very life of an addict. The first features a Vitamin Water Energy bottle with a pithy and carefree description of the tropics surrounded by a torpor-inducing bag of syringes. It reveals how the simplest things in life are tainted and overrun by addiction and how nothing remains innocent or untouched. The second is a photo of a long-stemmed rose lying across seven prescription bottles of Litium, anti-depressants, and anti-convulsants. And although there is no drug paraphenilia present, there is a reminder: a tube of Bruise Remedy Arnica Montana.

photographs, in particular, crystallize the chaos of not only Donahue’s installation but the very life of an addict. The first features a Vitamin Water Energy bottle with a pithy and carefree description of the tropics surrounded by a torpor-inducing bag of syringes. It reveals how the simplest things in life are tainted and overrun by addiction and how nothing remains innocent or untouched. The second is a photo of a long-stemmed rose lying across seven prescription bottles of Litium, anti-depressants, and anti-convulsants. And although there is no drug paraphenilia present, there is a reminder: a tube of Bruise Remedy Arnica Montana.

According to the Mass Department of Public Health, last year 79 percent of people who died were white men — like Dylan Donahue, and 54 percent of those people died from opioid overdoses and were between the ages of 25 and 44 — like Dylan Donahue. With that statistic in mind, Cost of Contentment becomes a photo diary of a tightrope walker’s shuttle between life and death. As the title suggests, the cost of this quest for contentment is considerable and the ultimate cost tragically irreversible.

If you are struggling with addiction, this exhibit may serve as a trigger. Regardless, it is for adults only.

Dylan Donahue’s Cost of Contentment will be on display through February 25 at Anchor House of Artists, 518 Pleasant Street, Northampton. Gallery hours are Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, and Saturday 1 p.m. – 6 p.m. 413-588-4337. anchorhouseartists.org