On January 20th, 2017, I attended (and also played) an anti-inauguration “bash” at the Flywheel in Eastampton. Everyone was reeling and processing — the whole day was harrowing and bleak.

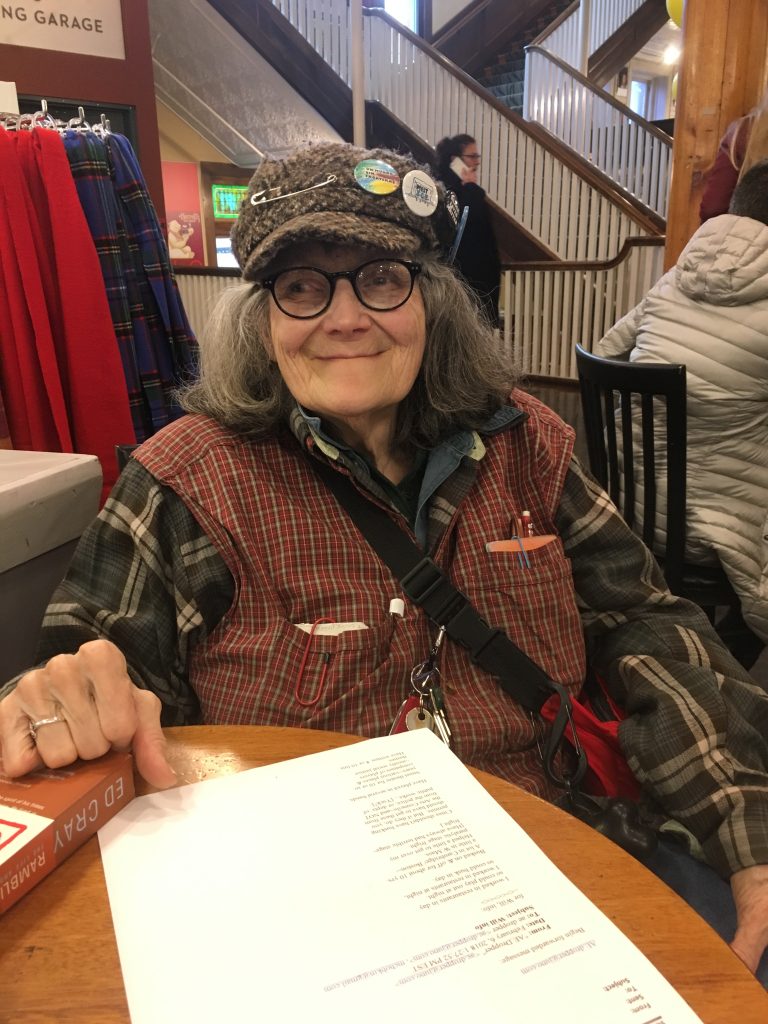

That night, for the first time, I heard Diana Davies (who goes by Moggie to people who know her) play for the first time. Her music transported me to a sound, a vision, and a world that was radically different than the one we were walking into that day. While the world felt rudderless and more uncertain than I had ever known it, Moggie stood like a statue with her guitar in the Flywheel and sang songs about becoming more free and kind.

The performance stuck with me. A couple months later, I tracked Moggie down and told her how much I loved her performance and she said she would make me a tape, which she did. It took us many more months to coordinate an interview — I wanted to know where her music came from and, when we finally sat down, she was eager to tell me.

During our interview, Moggie handed me several pages of typed notes full of these little free-flowing vignettes explaining her thoughts on the ‘90s Northampton scene that she came up in. While the notes did offer some insight into the act of making music, they were far more concerned with the ethics of making music and living more generally.

Here she proclaimed that cities shouldn’t have busking permits, she’d rather work at a show than sit around at one, the mix shouldn’t be too loud (for example, if you’re in a room for 500, you shouldn’t adjust the sound for 5000) and that shows should be all ages. Adding that she’s all for fake IDs to get into shows, not for drinking, but come to think of it, she’s against all IDs, anywhere, ever.

She supported the Flywheel “since before the beginning,” she “won’t play anywhere owned by Eric Suher” and when she played in the “Women’s music scene” in the ‘90s she found it to be, with a few exceptions, competitive and non-supportive. Also, she’s straight-edge and mostly-vegan (except cheese from samples).

While all these idiosyncratic rules seemed a bit cumbersome to keep track of (She kept remembering them as we were talking — “I didn’t write down my spiel on cassettes,” she said mid-thought: Cassettes are the “most democratic form of music production” — because they’re cheap, easy, and anyone can record on them.), they are a foundation to stand on.

Moggie’s 1996 cassette, Twelve o’clock girl in a nine o’clock town, released on Red Hot Records, is just Diana and her guitar. She strums rhythmically and urgently to make room for the lyrical storytelling about people, places, and righting wrongs, while advocating a sort of ethical hedonism. She sings about the injustice of a landlord evicting a tenant to then let the dwelling sit empty and women who were disappeared and killed at the hands of rotten men. She cites English songwriter Billy Bragg as an influence. Similar to the ‘60s counterculture figures — like Dylan and Janis Joplin — who her music evokes, her vision of the good life is hanging around a cafe with music and mingling with other musicians and artists.

Since the scene has changed, venues and scenester haunts have have been shuttered to make room for boutiques, craft beer, and for-profit weed, Moggie continues to play percussion — now with Flame n Peach and the Liberated Waffles.

“You can’t bring us to our knees, we’ll live as we please,” she sings on Lives to Remember, which was optimistically true in 1996 as well as now.

Will Meyer writes the Advocate’s bimonthly Basemental column, you can reach him at wsm10@hampshire.edu, or @willinabucket.