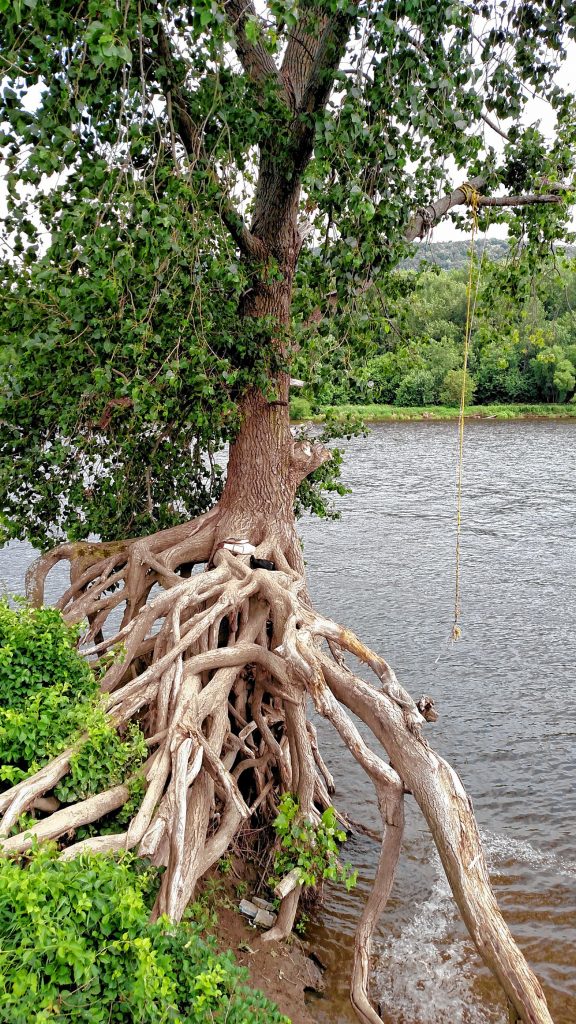

I sit on the twisted root system of a great tree, a shelf of exposed roots thrust out over the Connecticut River at the edge of the Northampton Meadows. I’m perched 15 feet above the olive water. The muddy bluff has been licked and sucked away under the tree by years of the river’s lapping tongues. Even now in the calm of early summer, the water bites chunks of greenish sediment from the bank.

The roots offer a writing nook of romance and natural vigor, notebook open on my knee. Above me, a rope swing hangs from one thick branch. A wooden ladder has been nailed into the trunk. Swallows nip over the water. The first clouds of a promised later thunder and hailstorm prepare themselves.

As I write, I’m interrupted by a band of shirtless teenage boys arriving in a muddy blue Mazda. They flit onto the tree all around me. Soon they’re leaping from the rope into the water like flying fish.

The most potty-mouthed of the lot is the youngest, making a great point to prove himself among his elders. He must be 13 or 14, with narrow chest, floppy brown hair, long shorts.

“That was f—ing sketchy!” he shouts, emerging from the water after a long jump. “Dude, if this gets cut down I’ll be so mad.”

They instruct one other on the best way to keep their feet up, so as to get high enough for a flip at the top of the rope’s parabolic trajectory. “I don’t worry about keeping my feet out of the water,” swaggers the youngest.

“It’s because you’re short,” grunts an older boy.

“No, it’s because I grab it mad high,” insists the first. “I jump out one-handed, then when I jump I grab right here.”

They’re oddly restful, this troupe of Northampton boys, talking and spitting and pausing to piss into the bushes down the bank. One of them asks me, in afterthought, if they’re bothering me. “Not at all,” I truthfully reply.

As I make my way off the roots to go home, the boys are emerging from the water, crawling off the roots, finishing their swim. “Get your b—ch—ss up here,” calls one to the other; “your mom’s calling.”

Two years later, it is mid-April. On a rare warm day I grab my bicycle for an early spring pilgrimage to the Meadows. My bicycle bumps over potholes in the dirt farm roads.

As I arrive on the bank of the river I am brought up short by a different look to the landscape. An empty look. It’s disorienting at first. Am I in the right place?

I am. The tree has fallen. In the violent winds of this late winter’s storms, the bluff has given way, and the tree lies along the bank, half in the water.

At my arrival two wood ducks sheltering by the trunk explode into the air. They vanish. Fat buds still cap each of the tree’s twigs.

A line from Barbara Kingsolver’s environmental novel Flight Behavior springs into my mind.

One of God’s creatures of this world, meeting its end of days.

Kingsolver’s book tells of the extinction of a whole species – not the tumble of one tree. Her fictional tale imagines the yearly migration of monarch butterflies gone badly awry, threatening to wipe out the monarchs completely.

But in this time of extinctions, individual deaths echo big. Every loss feels like a blow.

It’s made me value each individual more, and cling to the idea of their life. One tree feels like an avatar of a toppling thousand. If this one goes, will another take its place?

Recently, two iconic centenarian trees had to be cut down on Smith College’s campus, victims of aggressive fungal diseases – an oak and a beech. At a spring concert on May 1, A Musical Tribute to Smith’s Trees, a concertgoer approached one of the Botanic Garden’s landscape curators. “You cut down my copper beech,” she mourned.

Natural beings like these do inspire a sense of belonging, of direct individual companionship. With long-lived beings like trees, the absence is particularly poignant. It’ll take a hundred years to grow another.

Speaking of long lives, two years ago, I wrote of visiting Cape Cod to watch northern right whales just offshore, breaching and blowing and fluking not 20 feet from where we stood. They can live as long as 70 years.

Then, there were just 500 of them worldwide. This year the number has fallen precipitously, to fewer than 450. No calves were born to the whales last year, a worrying indicator of the stress they’re under.

These whales, once called the “right” whales to hunt by whalers, are slow-moving and like to float near the surface. Their habits made them easy to harpoon. Whaling has largely ended, but right whales’ population never recovered.

They’re highly vulnerable to collisions with boat propellers. They also can get tangled in fishing gear and drown, comprising almost 60 percent of right whale mortality. Seventeen died last year from entanglement.

Food availability may also stress them. Rapid warming in the Gulf of Maine has caused a drop in phytoplankton, the whales’ main food source.

At a loss of 50 animals biennially, the right whales will be gone from this earth in 18 years. No longer will these sleepy beasts wave shining blue fins at us as we stand on the beach, as if they know we’re there.

We can call our legislators, pressure them to put laws in place to prevent fishing entanglements or boat collisions. Researchers have a good sense of what changes would make a difference for right whales.

It’s possible to change, for one species or all of them. But will we?

When a species goes extinct, it’s more than just a type of creature we lose – when natural land is replaced by buildings, when climate change makes a region uninhabitable for flora or fauna, when a landscape changes forever.

It’s a way of living, a familiarity of place. It’s boys jumping gleefully off a rope swing into a flowing river.

As I stand by the bank of the Connecticut, the fallen tree is big enough that some branches poke up all the way to the edge of the bluff where I stand.

I wrap my fist around one twig. The buds poke between my fingers. They were ready for spring.

For a moment I hold the tree’s hand. It’s still alive for a little while longer, sap moving under the bark.

“I see you,” I murmur, the best I can do. “I’ll remember you.”