“It’s like you’re going to a foreign country… Do you need a passport?” Letha Dollarhyde of Letcher County, Kentucky, said this — partly in jest, partly not — about coming to Leverett, Massachusetts, when she visited here last fall. Our Hands Across the Hills project is about “Dialogue and Cultural Exchange.” “Cultural exchange” — isn’t that the phrase used by the State Department when American artists and scholars travel to other countries? So I asked myself: Are we this divided that a region of our country feels truly foreign? Would I be in a “foreign country” as I arrived in Whitesburg, Kentucky, for a return Hands Across the Hills visit April 19-23?

Sign on porch of the Kentucky house where three Leverett women were hosted by a Letcher County resident. Photo by Sharon Dunn

As we crossed into Letcher County by car, a handmade sign with balloons bobbing in the breeze welcomed Hands Across the Hills. The looming beauty of the mountains turned us silent in wonder. The shades of green tender leaves emerging on thousands of trees, the redbud trees in bloom on the roadside — so many mountains, close together, slender emerald green valleys in between. Beautiful mountains, like the Berkshires, like the Green Mountains. Driving into Whitesburg, we found most of the main part of town is red brick, just like our New England towns. Not a foreign country.

Fourteen of us, members of Hands Across the Hills, were reuniting with the coal country folks who had visited us in October 2017 in Leverett. All of us had spent hours in safe, private dialogue sharing deep feelings, exploring our differences and similarities; the 11 of them had stayed in our Leverett homes; we had eaten with them, sang and danced with them.

Now we were gathered on the home ground of folks we’d come to consider friends. They welcomed us. They’d planned three days packed with dialogues and conversations about community and family. We were educated about their economic distress, about the opioid crisis they face. There were real differences and a great deal we shared.

Yes, we began planning this “cultural exchange” almost a year ago, hoping to bridge a stark, painful political divide. After the November 2016 election, many Leverett residents wanted to understand how a rural area in another region could have possibly voted overwhelmingly for Donald Trump.

The divisive 2016 vote and how these Kentuckians now feel after more than a year of a Trump administration — these issues slipped into the background as we gathered face to face. Not that these issues disappeared, oh no. But our common concerns — wanting a steady good living, a future for our children and grandchildren — were in the foreground.

Hear authors Sharon Dunn and John Clayton speak about their experiences speaking with Kentucky residents on the Valley Advocate Podcast.

On Friday, our first day in Whitesburg, the county seat, we walked the small downtown, met the mayor, the chief of police, and the the library director. In the afternoon we settled in for our first dialogue session in Kentucky — in a building owned by Appalshop, the robust 50-year-old arts organization dedicated to community development that originally supported this project.

Closed dialogues have been at the heart of our endeavor, these times we sit in a circle and engage in talk facilitated by Paula Green of Leverett, whose experience in bridging divides and sustainable peace spans thirty years. Paula asked the group: “What changes have come about in our lives from our Hands Across the Hills experiences?”

One woman from Letcher County had been unable to speak to a beloved older brother — political views divided them painfully. After experiencing the dialogue process, she was able to engage and regain closeness with her brother. Another participant had considered moving out of Appalachia, but, bonding with Kentucky peers on the trip to and from Massachusetts, decided to stay in the Whitesburg community. Leverett members revealed they have created bonds of community and caring for each other that did not exist before. “I’ve met more folks in Leverett in the last six months than I have in the over 30 years I’ve lived there,” Tom Wolff of Leverett exclaimed.

We agreed that meeting face to face was an enormously positive and powerful experience. Face to face encounters let us see more clearly, to feel deeply what we share and to feel safe in our differences. The corollary is that, on the whole, the shouting media and politicians divide us and want us divided.

Kip Fonsh of Leverett said: “I learned in our work together that when you are talking, you are not listening.” And listening closely, deeply, is central to the dialogue process. We would have a second dialogue session on our last full day, Sunday.

Catering Business Started in an Abandoned School

Our Kentucky hosts wanted to give us a good look at Letcher County and the organizations they are developing to strengthen community and economic stability.

Leverett and Letcher County participants circling up for dialogue facilitated by Leverett’s Paula Green. Photo by Sharon Dunn

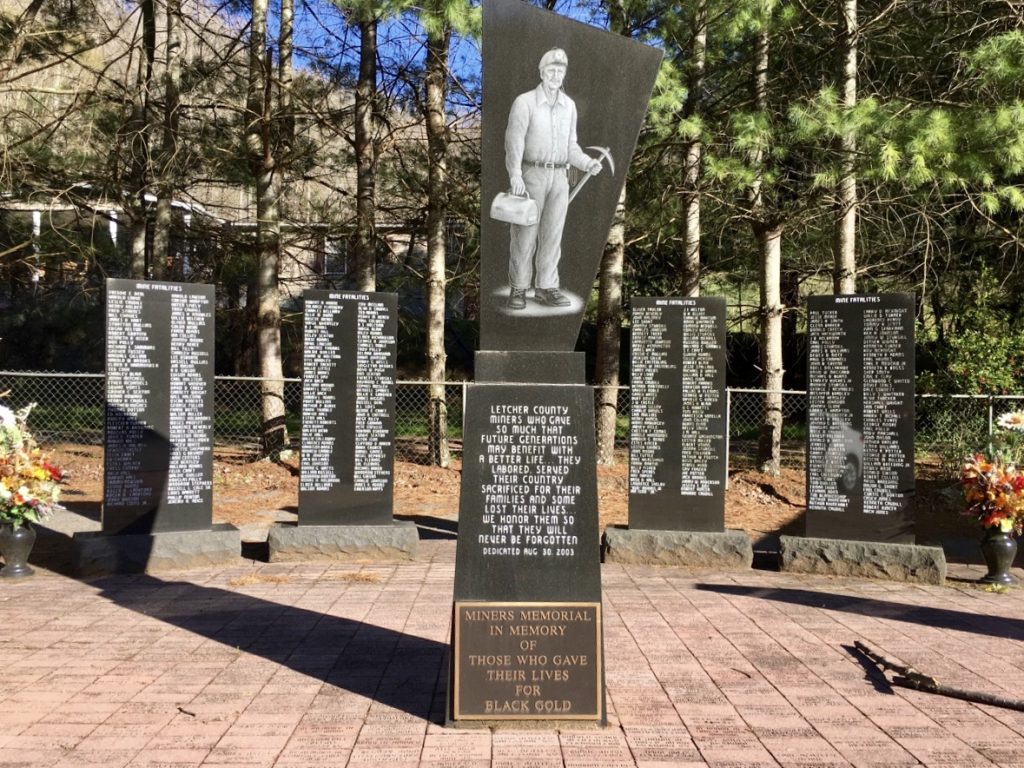

First, we visited the Hemphill Community Center, just north of the coal camp town Neon. Next to the parking lot is the Letcher County Coal Miners Monument, with hundreds of names carved into three black monuments and etched in the bricks underfoot: In Memory of Those Who Gave Their Lives for Black Gold. The number of names for a small county of 23,000 seemed very large to me, bringing to mind the stories we’d heard from our Kentucky friends of brothers, fathers, sons who had died through mining accidents and black lung disease.

The Hemphill Community Center operates in the basement of an abandoned school, in its kitchen and cafeteria. Here Hemphill native Gwen Johnson has created a catering company, a brick oven bakery she’s named The Black Sheep, and a series of Friday Nite Pickin’ music and community dinners. Gwen spoke eloquently in our October Leverett public event about her desire to vote for a woman as president, but how she ultimately could not, because Hillary Clinton’s position, as Gwen understood it, was “to end coal.” “We have coal dust in our blood,” she said.

Gwen introduced her team, the Hemphill T-shirted crew who had done the baking and cooking for dinner. All are recovering addicts who have served time in jail, and now have been given a chance to be part of something brand new in this community. One of the crew, a woman, said with a laugh, “You never know how much time you have on your hands till you get sober!” The crowded room roared with laughter.

Post dinner, the live music started up. Leverett’s Stacey Lennard won a cake in a cake walk! A tall cowboy-booted Kentuckian, a handsome elder, invited me to dance; his accented voice was hard for me to make out through the music, though I did catch him saying he’d won dance contests in all 50 states. Yes, he was a wonderful dancer!

We witnessed energy going into a new business enterprise — the catering company and bakery. We saw the effort to create and give pleasure to a community. The center gives employment to recovering addicts often turned away as unemployable, who were described to us as enthusiastic contributors to the Hemphill Community Center.

Shriners’ Hospitality

On Saturday the Mountain Shrine Club of Whitesburg invited us to a community breakfast, the last of their cold weather season. After hearty Kentucky fare that included biscuits, gravy, and several meats (plus yogurt and fruit put out just for us), Leverett folks made a presentation about why we wanted to connect to Letcher County, about our dialogue work and about our town.

Because the Shriners were likely the most conservative group we would meet on our trip, I was wondering what kinds of questions the audience might ask in our Q&A. Here was the most serious question: “What do people like you, with all your education and development, owe people like us? What is your responsibility toward us?”

This is a central, hard question. It was the core of several emails I received from close friends, passionate progressives, who, hearing of Hands Across the Hills going to Kentucky, wrote me in exasperation: “Blue states already pay so much more in taxes than red states, funds that go to red states to support them. We already give and give!”

I have arrived at my own answer to the man who asked this question: I feel my personal responsibility is to see you as who you are, to understand your complex situation as best I can, to offer what best I can. In my case as a writer and a former business person, it is to write as truly as I can, and to share my business experience.

Paula Green, who answered publicly, spoke of her commitment to economic justice and a living wage for all, our group’s willingness to work together on economic issues. “We are aware of the exploitation, extraction of resources and pollution that have plagued communities in your region. But we are not here to push solutions of any kind on you. We are here to get to know you.”

As I chatted with two Shriners minding the meal ticket and lottery table, I learned that the members of this club drive children needing orthopedic or burn care to Shriners hospitals as far away as Cincinnati, Ohio. One member has driven over 100,000 miles and his wife, over 30,000 miles. “I make a friend on every trip,” said this Shriner. Indeed, a few in our Leverett group have had their children cared for at the Springfield Shriners Hospital.

One of the lottery prizes laid out on that table was a shiny rifle, but I bought tickets for another prize. Years ago I shot a rifle — at Boy Scout camp in the Adirondacks with my son, and I actually enjoyed hitting the target. But I will never own a gun, I feel safer not having a gun in my house. Some of the Kentuckians we met feel the opposite: they feel safer with a gun — in the house, in a purse.

Talking with the two Shiners, I felt our differences (politics, guns) but I also felt I had something in common with these men, whose dedication to their community was similar to my own volunteer commitment over the years to non-profits in the areas of education and social services.

Celebrating Two Years Building a Culture and Economy

Our visit coincided with the two-year anniversary celebration of the Letcher County Culture Hub, an innovative approach to revitalizing distressed communities. At the center of the hub and its energizing force is Appalshop, the 50-year-old arts organization in Whitesburg. In only two years Culture Hub has created a network of 22 community-led organizations to work together to start businesses, revive cultural events, influence public policy and bring more and more citizens of Letcher County into the process of imagining and building a future together.

“The Future of Letcher County,” a staged play reading by Roadside Theatre, was created from stories told by residents all over Letcher County, KY. The play was part of the all-day celebration of the Letcher Co. Culture Hub. Photo by Sharon Dunn

The motto they have adopted is: “We own what we make.” This is a strong verbal antidote to the more than a century of natural resource extraction — timber, then coal — and exploitation (low wages, captive economy via company stores and scrip, poor health care, paltry disability benefits). We own what we make. Letcher County has taken that to heart and welcomes all ideas to secure their economy.

At the celebration, held at the Cowan Community Center, we first browsed an outdoor farmers’ market displaying honey, woven goods, maple syrup, artwork and more. A play The Future of Letcher County was performed by the Roadside Theatre in the Center’s beautiful building. This was a five-character reading — the actors created characters whose stories came from storytelling circles held county-wide. Storytelling, we learned on this visit, is the prime way of communicating ideas here. Everyone tells stories all the time.

After the play, the audience gathered in its own large circle. “What moved you in this play?” the dramaturg asked. We answered: the stories of economic struggle, homophobia and transgender bullying, opioid addiction, overcoming the stigma of being considered “white trash,” the awful choice that young people face: should we stay here near our families where work is hard to find, or relocate far away where we can make a living.

For me, social and economic issues of Appalachia that were mostly abstract became more real as I listened to actual stories. For instance, the concept of the opioid crisis transformed to what is lived day in and day out. A story that struck at me: a Kentucky woman was forced to move in with her mother, because the youth in their own family constantly invaded her mother’s house, to rob her of a toaster, a microwave, to finance their opioid habit.

Traveling to a Coal Mine

Hands Across the Hills members loaded onto a cart about to enter a Harlan County coal mine closed in 1963. Millions of tons of coal were mined here beginning in 1917. Photo by Sharon Dunn

On Sunday, April 22, we toured Port 31, a coal mine active until 1963 in the town of Lynch. Here I was, in Harlan County, where the Academy award-winning Harlan County, USA (1976) documented the fierce struggle for union contracts, fair wages and benefits, and the intransigence and brutality of the coal company owners and their henchmen. The film showed the comradery of miners and captured the love of coal mining, the miners’ belief they were doing important work in building American industry, helping win wars — all this is what Herbie Smith of Letcher County had spoken of to us in October. The film also captured the strength of the women of this region, who organized picket lines and fought for rights for their husbands, brothers and sons. And indeed on our visit we witnessed the leadership of the Kentucky women we’d come to know — Nell, Carol, Val and Gwen — all weekend they were managing events and speaking in public, on behalf of their organizations.

On the way to Harlan County, as our van negotiated hairpin turns up and down the steep mountains, Herbie Smith, a filmmaker at Appalshop, recounted the cycles of boom and bust in the coal industry that have led so many Appalachian folk to believe the current bust will surely be followed by another boom. Boom has always followed bust before, so why not now?

How much coal remains in the mountains? Herbie tells us only a small percentage of coal has been extracted; huge reserves remain in Letcher County, only deeper down, difficult and expensive to mine. So, in coal country the feeling is, we have it, let’s mine it and provide livings for ourselves.

Yet today’s mining in eastern Kentucky is mainly done by machine, with humans serving as machine minders. As more and more power plants have turned to gas over coal, and as coal companies now favor the western U.S. reserves where coal is less expensive to mine, mining employment prospects in eastern Kentucky are dim. And suppose they weren’t dim. The digging by machine leaves far more dust in the air and yields much more black lung disease than mining used to produce.

Final Dialogue

Memorial to Letcher County, KY, men who lost their lives mining coal –names are etched on the four monuments and on each brick underfoot. Photo by Paula Green

Our final deep dialogue was held at the Benham School House Inn in Harlan County, another closed school transformed into a business. But first we heard another theater group, Higher Ground, describe their plays, again created from stories, oral histories of folks in their county. Their production Opioids, the Musical, involved 80, yes, 80 community members. A commissioned play called Needle Work highlighted the importance of needle exchanges. We wondered later could we bring this troupe to Franklin County, Massachusetts, to perform, to teach us how to create powerful socially relevant theater pieces from stories we tell?

Paula Green asked us as we began our dialogue that day to reflect on what questions remained for each of us. What questions had gone unanswered? We broke into groups of three, and each group wrote three questions on paper. We taped all the questions on the walls, then moved them, grouping similar questions. The greatest number of questions clustered around Trump, so we finally talked about Trump in our dialogue circle.

Two women, one each from Leverett and from Letcher County, who had not been with us for our hours of dialogue work in Leverett, went at it. “Can’t you see how all the achievements around environmental protection, consumer protection, regulation of financial institutions, all of it is being dismantled…” “Why can’t you overlook questions of Trump’s character and focus on the good things?”

One precept we learned from our past dialogue work was that blunt, blaming political cross-talk does not change minds. It raises the temperature in the room.

Others in our circle then took their turns to say that Trump was no longer the issue for them, that learning from and caring for each other have been fundamentally more crucial than discussing Trump on any terms.

In our very last formal gathering on Sunday we brainstormed: Where do we go from here? Ben Fink of Appalshop transcribed over 30 ideas for Leverett and Letcher County Culture Hub to work on together.

Some of those ideas: Expand dialogue partners to a third community; partner on gun legislation for better background checks and against assault rifles; connect with business ideas and non-monetary capital… We each shared a word about what this weekend meant to us. My word was “Impressed.” I had never seen anything like the Culture Hub being created in Letcher County, a concept which Appalshop’s Ben Fink is looking to export to other economically distressed regions of the U.S. Others’ words were: “Heart-filled,” “Uplifted,” “Hopeful,” “Excited.” Together we sang the Appalachian traditional folk song “Bright Morning Stars” and made our emotional farewells.

For each participant in Hands Across the Hills, the details of connection are different. We each had conversations with many different people, over meals, on car rides, at the farmers’ market. We all, Letcher and Leverett alike, are richer for knowing each other, for connecting in deep honest ways. We will be mining our experiences for a long time. A foreign country? No. We are fellow Americans.

For the latest news and projects of Hands Across the Hills, visit their website: handsacrossthehills.org.

Sharon Dunn is author of two books of poetry and a memoir: Under a Dark Eye: A Family Story. John J. Clayton, professor emeritus at UMass Amherst, is author of four novels and five collections of short stories, including his latest, Minyan: Ten Interwoven Stories.