How would you like to buy a bottle of Château Lafite Rothschild for $1.75? Maybe a bottle of Château Haut-Brion for $1.95? Interested in two bottles of Château Mouton-Rothschild for a whopping $2.95 each? Or go ahead and splurge on a case of Château Margaux for $25. If you are deeply infatuated with wine, these names are familiar to you. And you may be incredulous of my listed prices, as current vintages of these wines go for about $500 a bottle. But this is exactly how much Clifton Fadiman paid for these bottles of First Growth Bordeaux in 1935. And if the names of those wines are familiar to you and the name “Clifton Fadiman” is not, there is a book you must read.

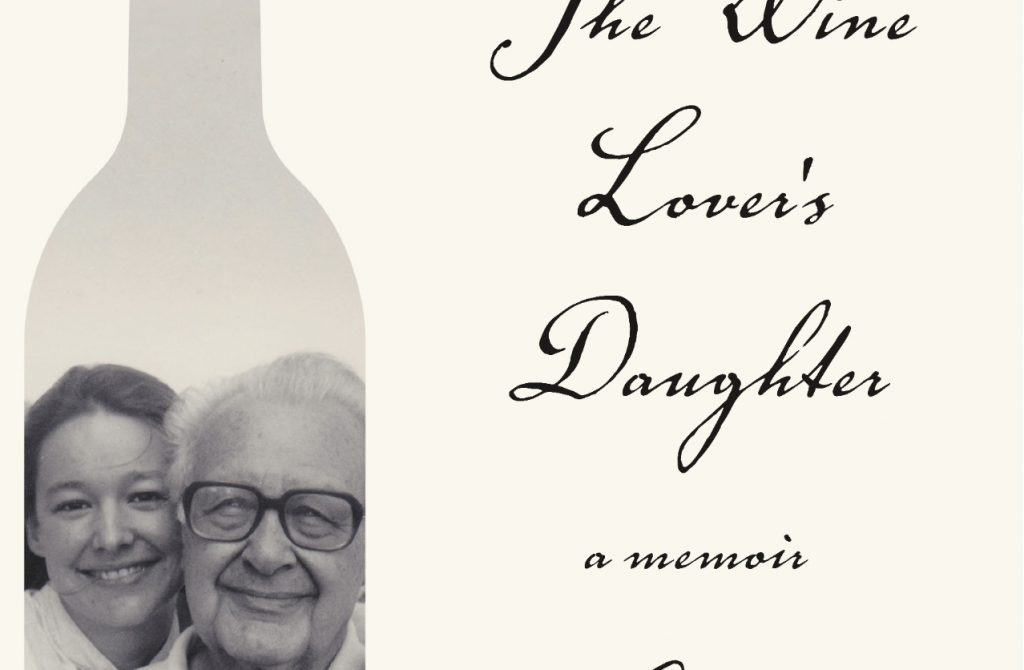

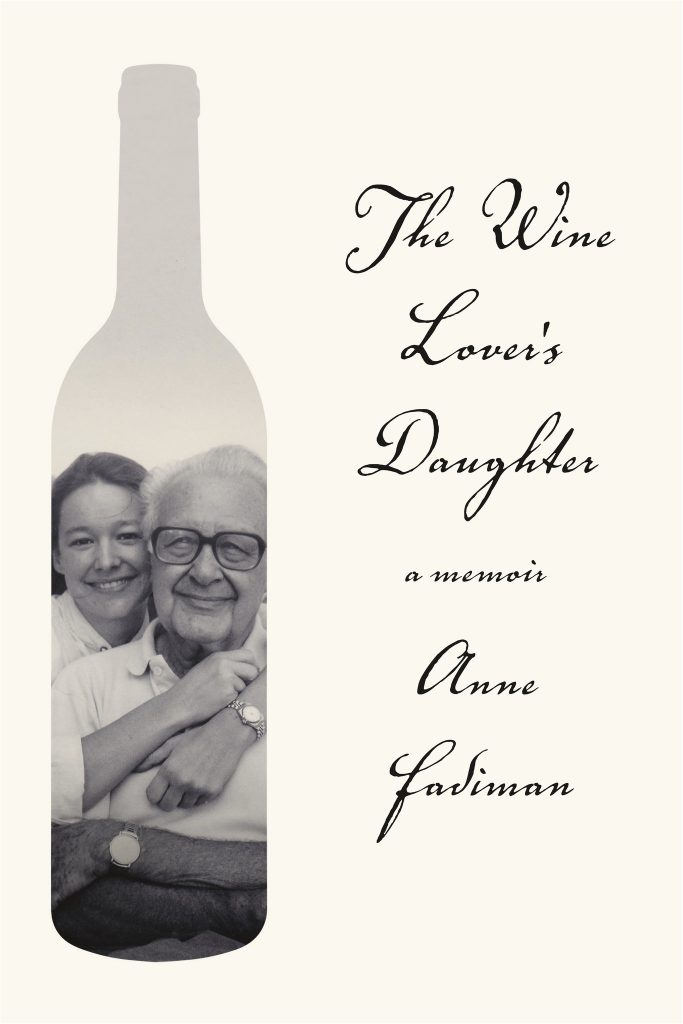

The Wine Lover’s Daughter by Anne Fadiman is a memoir that doubles as a loving and honest biography of the author’s father, who, among so many other astonishing accolades, may have been the person you should thank for introducing America to wine.

The Wine Lover’s Daughter by Anne Fadiman is a memoir that doubles as a loving and honest biography of the author’s father, who, among so many other astonishing accolades, may have been the person you should thank for introducing America to wine.

“The context for the wine part of the book is Prohibition. One of the things that made this all so exciting to me was realizing that ‘Oh my God, he started collecting wine two years after the end of Prohibition.’” In the book, Anne Fadiman, who lives in Whatley and with whom I spoke before her recent reading at the Whatley Library, details her father’s extraordinary life as one of America’s best known intellectuals of the middle Twentieth Century. Clifton Fadiman was the book reviewer for The New Yorker, judge for the Book-of-the-Month Club, editor of the Encyclopedia Britannica, radio host of the extremely popular radio quiz show Information, Please!, and carried on a lifelong love affair with wine.

After returning from a dramatic trip to France, where he tasted and fell in love with his first ever glass of wine, and where he successfully won back his first wife, who had been swept away by a Count or a Baron (even he couldn’t remember), Clifton Fadiman found himself in an America where wine was illegal. Then Prohibition ended. Anne says “And he becomes the editor at Simon & Schuster at the age of 28. One of the first books he commissioned, by Frank Schoonmaker, was a book about wine. It reintroduced wine to America.” Schoonmaker’s Complete Wine Book and Encyclopedia of Wine were hugely influential in educating post-Prohibition America about wine. Schoonmaker took Clifton Fadiman into his wine tutelage. Two years after Prohibition, Clifton Fadiman started his own wine cellar. And he kept exacting records in his “Cellar Book,” which is now in the care of the wine lover’s daughter. “I learned that on his first day as a wine collector he bought more than 900 bottles. So he clearly had been thinking about this for a long time.”

Anne Fadiman macerates her father’s story in his love of wine. His inauspicious origins as the son of Russian-Jewish immigrants in Brooklyn engender in him a sort of internalized anti-semitism. His love and knowledge of wine and literature act as an escape plan “cross the river” as Anne puts it, and to transcend what prejudices people may have held. And yet even with dinner guests like Groucho Marx and P.L. Travers and correspondences with E.B. White and a letter from a drunken Hemingway, Clifton Fadiman suffered from what many of us suffer from — a type of imposter syndrome, likely due to the actual anti-semitism Clifton Fadiman faced.

The book made me experience my own imposter syndrome even more acutely after reading about how influential his radio show was, and after reading the exquisite language that both Anne and Clifton use in their writing — and especially in their writing about wine. Anne quotes her father describing a wine as “a country-wench Rhône, surrendering at once its all,” and “to take wine into our mouths is to savor a droplet of the river of human history,” to which Anne responds in her book “a pronouncement I found a tad grandiloquent but whose sincerity I did not doubt.”

The book made me experience my own imposter syndrome even more acutely after reading about how influential his radio show was, and after reading the exquisite language that both Anne and Clifton use in their writing — and especially in their writing about wine. Anne quotes her father describing a wine as “a country-wench Rhône, surrendering at once its all,” and “to take wine into our mouths is to savor a droplet of the river of human history,” to which Anne responds in her book “a pronouncement I found a tad grandiloquent but whose sincerity I did not doubt.”

What’s remarkable about Anne’s own story within her father’s story is that Anne doesn’t like wine. “I don’t hate it. But I don’t appreciate it either,” she told me. A person who grew up in a household with the author of the legendary wine tome The Joys of Wine finds little to no joy in wine. And yet one can tell just by reading the book that she has more than a little wine knowledge. “Anybody who grew up around our table would know: ‘Oh, ‘59. What a great year!’” She writes that she had the First Growths memorized by sixth grade. “It’s not a body of language that I attempted to acquire,” she says. “It’s like mother’s milk, but instead it’s father’s wine.” And yet she still has no taste for it. But it wasn’t for lack of trying. “My father believed all palates are educable. And I figured I had an immature, childish palate.” At her brother’s 21st birthday party her father opened a bottle of 1934 Romanée-Conti, which would sell for around $25,000 right now if you could even find one. Neither she nor her brother appreciated it. Pearls before swine? She writes: “For a long time, I thought of that evening as the Emperor’s New Wine Tasting. I now realize it was the opposite. The emperor’s clothes were real. The populace was blind.”

Anne tried until she was in her forties to choke down some of the finest and most expensive wines the world has ever seen. But after attending a friend’s party she says “I was served Haut-Brion and I didn’t dislike it but I left a half an inch in my glass.” A fact that she writes would make her now late father weep. “Then I started on this interesting exploration into taste science and discovered that there is actually a physiological reason why wine tastes too strong to me. It was good news and bad,” she told me. “It was good that it was not a deficiency in character, but it was also sad, because I was never going to love wine. It was great news for the book!” And indeed, the chapter on taste science is fascinating, and if you are one of those people who can’t stand the taste of cilantro you are definitely going to want to read it.

What is Anne’s relationship to wine now that she has a biological excuse for not inheriting her father’s palette? Does she ever buy wine? “When we had a little book party at our house after I read at Broadside [in Northampton]. My husband made pie. So pie and wine. Not a classic pairing. But we served a Chassagne-Montrachet. And some of the guests were saying ‘this is the best white wine I’ve ever had.’ That’s the fanciest wine I bought in a while. But I never would have bought it for myself.” Still no wine lover. She remains “The Wine Lover’s Daughter.”

The book is surprising in that it is a largely loving look at a father/daughter relationship, without most of the traumas that we fathers so often inflict upon our progeny … especially we drinking fathers. But despite drinking from his superior cellar nearly nightly, her father was not an abusive alcoholic or anything of the sort. And her love of him as both a father and as an intellectual juggernaut is as present in the book as truffles, dark fruit, and cassis is in Chateau Latour. And if the names of Clifton Fadiman’s First Growth Bordeaux that I listed at the beginning of the article are familiar to you, you may notice one missing from the list. The fifth of Clifton Fadiman’s First Growths on his list, a 1928 Château Latour, was a gift. He didn’t need to break the bank at a whopping $1.95 back in 1935. The current average price of that 1928 vintage is about $3,800 a bottle. The excerpts from Clifton Fadiman’s “Cellar Book”, now in the care of the wine lover’s daughter, were written on backpages torn out of Schoonmaker’s Complete Wine Book, the book that Clifton Fadiman published. If you are a Francophile when it comes to wine, you may have Clifton Fadiman to thank, and you have Anne Fadiman’s The Wine Lover’s Daughter to read.

Tweet Monte Belmonte at @montebelmonte.