A poster hanging in the lobby at Chester Theater Company points out common roots and themes connecting Islam, Judaism and Christianity – for example, the Archangel Gabriel figures in all three religions’ core legends. It serves as prelude to the current production, which prowls around issues of faith and heritage in a fractious world.

Director Kristen van Ginhoven and a superlative cast have created an arresting rendition of Ayad Akhtar’s Pulitzer Prize-winning drama Disgraced, one of the most-produced and most-discussed plays of recent years – a play about internal contradictions which contains its own as well.

Director Kristen van Ginhoven and a superlative cast have created an arresting rendition of Ayad Akhtar’s Pulitzer Prize-winning drama Disgraced, one of the most-produced and most-discussed plays of recent years – a play about internal contradictions which contains its own as well.

It unfolds in the posh New York apartment of Amir, a prosperous corporate lawyer, and his wife Emily. He is of Pakistani parentage but rejects Islam as “a backward way of thinking and being,” and has taken an Indian surname so as not to be pegged as Muslim in this Islamophobic time.

S he is an up-and-coming artist, “white, lithe and lovely,” as the playwright describes her, who has immersed herself in Islamic art. Both are on the cusp of big career boosts. He’s on track for partnership in his firm, she’s up for inclusion in a career-making show at the Whitney Museum.

he is an up-and-coming artist, “white, lithe and lovely,” as the playwright describes her, who has immersed herself in Islamic art. Both are on the cusp of big career boosts. He’s on track for partnership in his firm, she’s up for inclusion in a career-making show at the Whitney Museum.

Juliana von Haubrich’s set neatly defines their tastefully opulent milieu, from the minimalist architecture to the leather-and-stainless-steel dining-room set to the polished marble floor. Above the faux fireplace hangs a painting of Emily’s, a geometric starburst inspired by Islamic mosaics, the image split in two and its divided center a little off-kilter. Metaphorical? Absolutely.

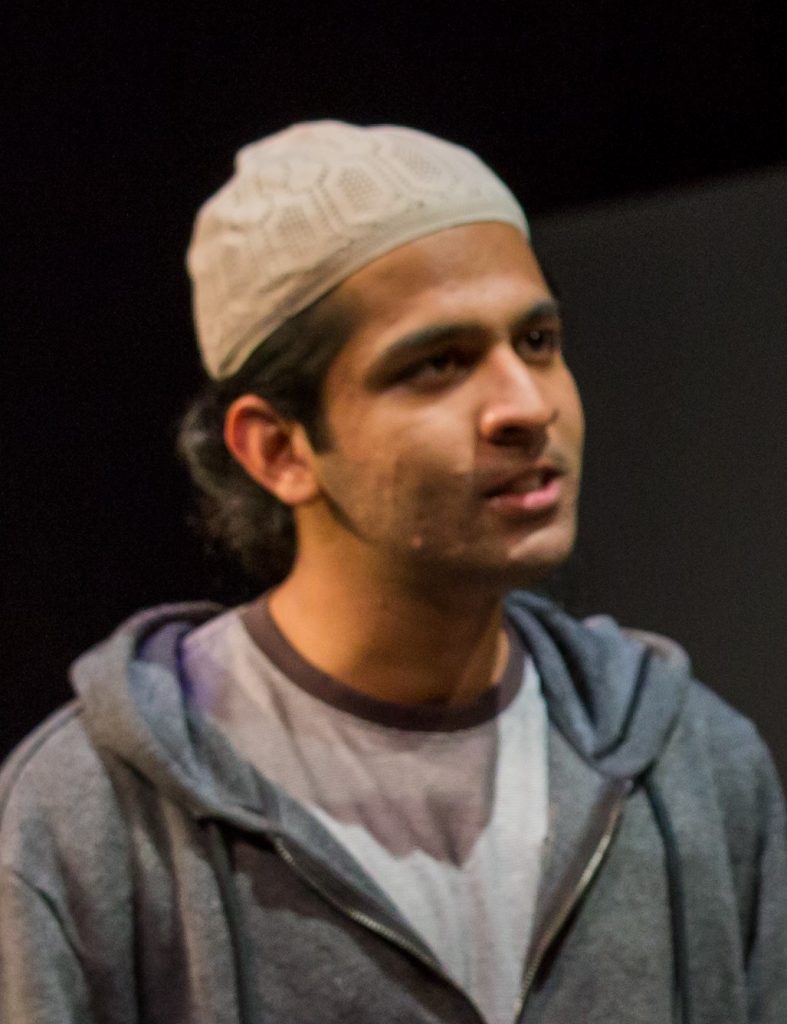

Amir has a nephew, Abe (Abuzar Farrukh), whose imam is accused of terrorist sympathies. When, reluctantly but at his wife’s urging, Amir makes a supportive statement on the man’s behalf, the resonances threaten his career and shake his sense of self.

Amir has a nephew, Abe (Abuzar Farrukh), whose imam is accused of terrorist sympathies. When, reluctantly but at his wife’s urging, Amir makes a supportive statement on the man’s behalf, the resonances threaten his career and shake his sense of self.

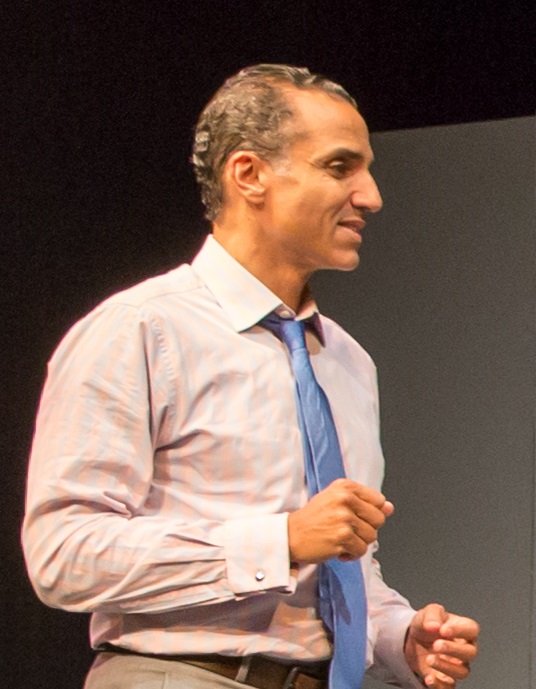

Amir is every inch the high-octane lawyer, shooting the cuffs of his $600 shirts and bullying his subordinates, but in J. Paul Nicholas’ fine-tuned performance we also see the guarded, apprehensive air of a man who knows he stands on slippery ground.

Kim Stauffer’s Emily, by contrast, is quite at home in her skin, gracious and supportive, but rather tone-deaf – defending Amir from a racist slight but dismissing his fear over the repercussions of his gesture on the imam’s behalf.

Two other characters complete this interlocking, multicultural circle: Jory, black, a colleague of Amir’s (Christina Gordon, a statuesque vision of confident chic), and Isaac, Jewish, the Whitney curator who’s considering Emily for the show (Jonathan Albert, a casual jeans-and-sportcoat contrast to his elegant wife).  The heart of the play is a dinner party with the two couples, where cocktails loosen tongues, spilling forth secrets, recriminations and home truths, and blood turns out to be a little thicker than assimilation.

The heart of the play is a dinner party with the two couples, where cocktails loosen tongues, spilling forth secrets, recriminations and home truths, and blood turns out to be a little thicker than assimilation.

Akhtar’s play wrestles with thorny issues of identity, assimilation and appropriation. Every character, in one way or another, has stepped away from their root cultures and made compromising choices in order to succeed in this still-WASP-dominated world.

Akhtar’s play wrestles with thorny issues of identity, assimilation and appropriation. Every character, in one way or another, has stepped away from their root cultures and made compromising choices in order to succeed in this still-WASP-dominated world.

All but one, that is. Emily, too, bridges two worlds, with her interest in Islamic art and her marriage to Amir. But there’s a whiff of exoticism in both, and alone of all the others, she hasn’t paid a price in accommodation or denial. Everyone else’s position is challenged at some point, but her white privilege is not (something it took this white critic’s POC partner to point out).

The piece deploys some rather mechanical plot twists to achieve its dramatic ends, straining credulity and diluting its impact. But Akhtar’s fearless engagement with his subject, and Chester’s riveting production, make this one of the summer’s most stimulating shows.

Photos by Elizabeth Solaka

If you’d like to be notified of future posts, email StageStruck@crocker.com