Western Massachusetts is well known as fertile ground for farming, but also for ideas. Sometimes these ideas come from the many classrooms and laboratories of our institutions of higher learning, but if you look carefully, you can find them in some pretty unexpected places, too.

This issue, we scoured the Hill Towns to find some out-of-the-box thinkers and now present to you our findings: an eccentric inventor in Ashfield, a visionary artist in Shelburne Falls, and an enterprising author and disaster preparedness expert in Cummington. Enjoy!

An inventor focused on heating clean

It wasn’t always smooth sailing for Ashfield inventor Tom Leue. When making his own brand of biodiesel, an alternative fuel made from plant

matter, he accidentally set fire to his workshop and burned it to the ground.

Still, his commitment to selling biodiesel (made by other people) has lasted 19 years. Now Leue has come up with an invention that will allow users to heat their homes using unfiltered used vegetable oil — the same material used in fryolators and other restaurant settings. He is selling it through his business Yellow Heat. The system is many times cleaner than petroleum-based systems, and Leue sees it as his small contribution to fighting against climate change.

“I started in 1999 making biodiesel and that wasn’t very profitable,” he said. “There was a lot of overhead, a lot of capital costs and regulations, and then I had a fire.”

Leue’s biodiesel workshop had originally been a garage, then a goat barn, and then a maple sugaring house. While a maple sugar shack is built to lose heat, Leue needed his biodiesel refinery to be insulated, and he decided to use plastic insulation.

Following the failure of a thermostat, one batch of biodiesel (batch #624) started bubbling uncontrollably, Leue said. That was in 2005.

Melted plastic dripped into Leue’s head as he made his escape, leaving a permanent white scar on his head. That was the end of Leue’s career making biodiesel, but he has continued to work with the fuel, selling and distributing it up through this year.

“The fuel is a remarkable fuel, but it is better if someone else makes it,” he said.

Now Leue is wrapping up his biodeisel business to focus on his new invention, a heater that runs on untreated vegetable oil.

“Biodeisel is a good fuel for the environment and good for the engine, but it is a premium fuel,” he said. “I wanted to heat the shop, and biodiesel wasn’t a practical way of doing that.”

Leue turned to the idea of untreated vegetable oil, which differs from biodiesel in that it is a lot cheaper, but has much more of a tendency to clog. Leue said the oil is basically free, and can be collected from willing restaurants who have finished using it to cook french fries or other fried foods. But it can’t be used in conventional oil burners because it clogs them.

Based on a concept developed by inventor Robert Babington, Leue developed and patented a device consisting of a hollow ball with a fine hole through which a jet of air passes. Because it is only pressurized air that passes through the hole, it can be used to ignite dirty oil, including waste vegetable oil, he said.

One obvious question: what about the smell?

“It smells like home cooking if you were raised that way,” Leue said. “Or like you live next door to McDonalds.”

Leue said he much prefers the smell of vegetable oil to petroleum-based oil.

The big advantages are environmental and cost. Using his device to heat with vegetable oil cuts down his carbon emissions to 2 percent of what they would have been with a conventional heater using petroleum-based fuel, he said. And the fuel is extremely inexpensive, or — if you happen to own a restaurant — free.

Unfortunately, the concept isn’t quite ready for mass production. Leue said that there is enough used vegetable oil to cover 8 percent of the heating needs in Massachusetts, but that vegetable oil is not on a list of nationally certified fuels. That means that insurance companies will not cover the device to heat people’s homes.

The device can, however, be used in farms and businesses, he said.

His goal is to make and install 100 units. He is already up to 10. It takes him about a week to make them, and depending on parts a buyer might already have (like an oil tank), the cost can be up to about $2,000.

“It isn’t like I can convert the whole state to vegetable oil; there isn’t enough available,” he said. “But 100 million gallons of vegetable oil are shipped to Africa and South Korea and Europe from the

United States, and that seems a shame to export 100 million gallons a year and then turn around and buy [petroleum-based] oil from other countries.”

In addition to selling the units, Leue plans to supply his customers with vegetable oil fuel. He has purchased a truck to pick it up from three local waste oil distributors and deliver it to people who sign up for that service. He calls the service CHERE (pronounced “cheer), based on the three companies he collects from — Champion in Springfield, Echo in Holyoke, and ReEnergizer in South Hadley.

“They sell wholesale to major biodiesel companies, but I’m able to offer them a significantly better price,” he said. “I buy it from them, deliver it to my customers at 20 percent off the cost of heating oil whatever it is on that day.”

Leue does not necessarily see his invention as a big money-maker. He works part-time as a sanitary engineer designing septic systems, which pays the bills.

“I am a biofuel developer from lunch until dinner time,” he said. “I make the money in the morning, and I spend it all afternoon on Yellow Heat.”

Leue said fossil fuel consumption is harming the planet, but biofuels are only a small piece of the puzzle. While he is pleased with his ianvention, he said he understands the scope of the problem.

“My little bit of it is a drop in the ocean, but hopefully it is a valuable drop,” he said.

For more information on Leue’s invention, visit www.yellowheat.com.

A gentler approach to a ‘personal apocalypse’

There are a number of misconceptions about disaster preparedness. If you’re on the extreme end of the continuum, you may think stockpiling guns and ammunition is your best bet at surviving a  catastrophic event. If you’re not prepared to shoot your neighbor for a can of beans, you’re probably going to take a gentler approach.

catastrophic event. If you’re not prepared to shoot your neighbor for a can of beans, you’re probably going to take a gentler approach.

Cummington resident Kathy Harrison is dedicated to community. She’s an emergency preparedness expert who has spent the last 30 years perfecting the art of survival. And though hoarding weapons is not her thing, she is, nevertheless, preoccupied with disasters.

Because disaster, she notes, isn’t just confined to science fiction notions of apocalyptic events.

“Even the more personal things [like] you lose your job [or if] you have a house fire. All of these things are your personal apocalypse,” she warns.

It was a personal crisis that led Harrison on her journey to preparedness.

“One year I had a new baby and he got really sick in the middle of a terrible ice storm …. It was clear that we needed to get the hospital, but we couldn’t get out; the road was blocked.” Harrison’s husband eventually managed to get the road cleared and they were able to get to the hospital.

“It was a gastrointestinal thing and he spent the next week in the hospital. And it occurred to me that all I really needed was a rehydration mixture, which is easy …. And I didn’t have that simple thing and it was ridiculous. I should have had that on hand; I have it now, I can tell you.”

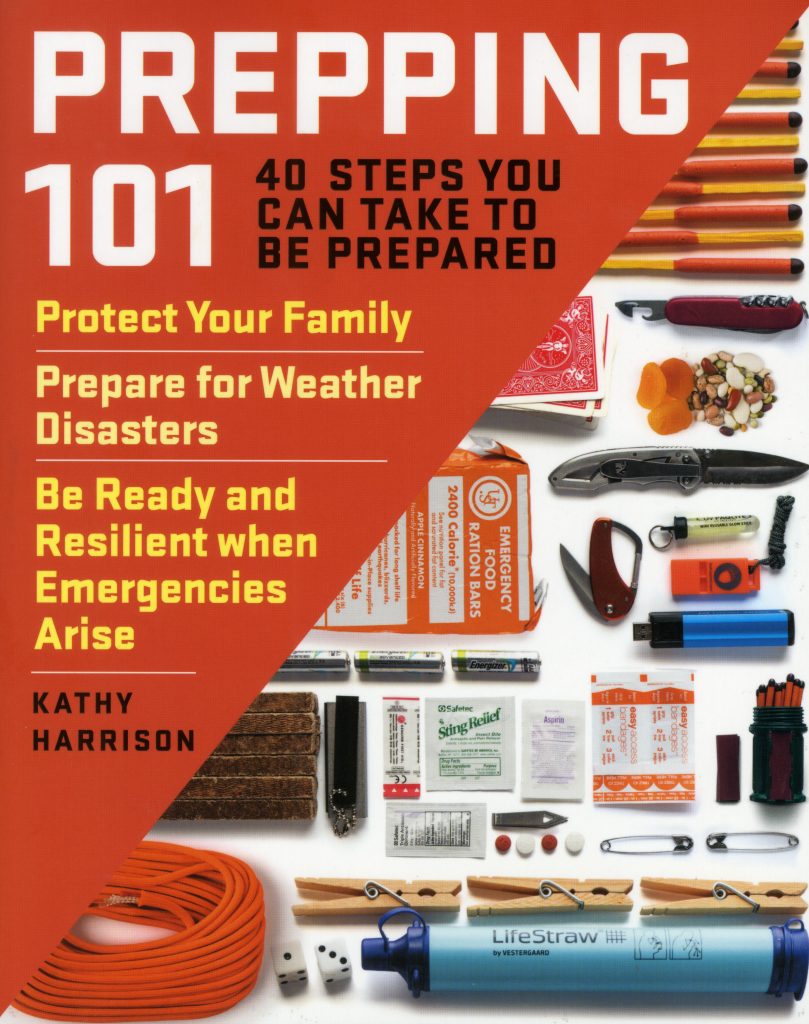

Harrison is the author of five books, two of which are dedicated to disaster preparedness. Prepping 101: Forty Steps you Can Take to be Prepared, published this year, is a 175-page guide to hoping for the best and preparing for the worst. Harrison breaks down the business of how to be “ready and resilient when emergencies arise” in a reader friendly non-linear format.

From creating a preparedness binder filled with critical personal documents, to running practice emergency drills, Harrison’s book gently but firmly guides would-be preppers for emergency situations ranging from extended power outages to wide scale food shortages.

“One of the places where we’re most vulnerable is our very fragile ‘just in time’ delivery system. It’s said that we have three days worth of food on the grocery store shelves. And that’s actually only true if there’s not a run on the grocery store.”

Harrison also notes the availability of food is dependent not only on having reliable computer networks, but also on having an undisrupted and reliable fuel source. The United States alone has suffered two oil shocks in the last 50 years. One in 1973, the other in 1979.

“You don’t have to take it seriously,” she says, “if you’re convinced that nothing awful is ever going to happen that will take down the grid for several weeks or have a supply disruption that is major. [Or] if you’re convinced that there will always be plenty of energy.”

The reason some may find Harrison meticulous planning abnormal may be rooted in what she calls “normalcy bias.”

“If something has been normal for you forever, it is impossible for you to look ahead and say ‘what is normal for me now was not actually normal less than 100 years ago. That normalcy bias puts us in a bind when we’re slapped with reality,” she says.

But we don’t have to use much imagination to ponder a world in which catastrophe strikes and life as we know it is changed dramatically. It’s hard to ignore the increasingly unpredictable and calamitous weather patterns that have plagued the globe these last few years — calamities that oftentimes disrupt power supplies.

In Puerto Rico many are still living without electricity eleven months after the devastation of Hurricane Maria.

And Harrison also notes: “During Katrina, one of the issues … was it took out all those [gulf] refineries, and the price of oil spiked right up. It’s one thing for me to say ‘I’ll suck it up and pay seven dollars for a gallon of gas to go the market, but if you’re living on the fringes and you’re poorer, you don’t have that option.”

One of the tenets of Harrison’s emergency prepping is taking into consideration the well-being of the entire community during a crisis, and that may be one of the biggest differences between Harrison’s emergency prepping and the motivation of doomsday preppers.

Whereas many doomsday preppers are most concerned about fending off intruders who threaten their stockpiles, Harrison says, “I am best served if my neighbors are my friends,” she says. “I’m not food secure if my neighbors are not eating.”

To that end, Harrison says she and her neighbors already work together sharing chickens and pigs. She is also a part of the Cummington Emergency Response Team (CERT).

“What we’re doing right now is compiling a list of those people who are disabled, people who are very old, or those who are alone, so that we can check on those people if there’s an emergency. I don’t want to ignore them. This is my extended family.”

In Prepping 101 Harrison shares her plan for designing a food storage program.

“Having some food put back is a really good idea, just a little thing to get you over that hump or learning how to grow anything on your plate,” she says.

She walks readers through planting small gardens, the methods of preserving foods, and safe food storage. She also covers topics like talking to kids about a crisis situation, caring for pets, and handling waste.

“I completely understand the desire to think about something else … [but] it’s my job to prepare now to ensure my family is protected,” she writes.

In her introduction Harrison ticks off the dangerous realities that threaten the systems under which we live: Political unrest, rapid climate change, financial market fluctuations, the threat of disease pandemics, and cyberwarfare are all active dangers. But Harrison, ever the gentle guide, warns against panic.

“You don’t need to be scared,” she advises. “You just need to be reasonable, you need to be organized, and you need to be thoughtful about what the future might hold.”

More information on Harrison’s latest book can be found at www.storey.com/books/prepping-101.

Creating his own worlds with glass

Josh Simpson painstakingly designs and creates planets in a classic New England dairy barn turned workshop next door to his home in the Franklin County hill town of Shelburne Falls. His planets aren’t made of landmasses, oceans, or atmospheres, but layers of glass designed to evoke the imagination with spaceships seemingly hovering above emerald green glass continents with swirling blue ocean currents.

Simpson is a world-renowned glass artist who has had his work showcased across the planet from the Netherlands to Tokyo, Japan. For more than 40 years out of his almost 50-year career he’s created his own unique glass planets ranging from small pieces that fit in your hand to platter-like ringed planets as well as pieces inspired by galactic landscapes shot by the Hubble Space Telescope.

He said his inspiration for his glass planet art was from space exploration in the 1960s and 1970s as well as classic science fiction authors such as Robert Heinlein and Isaac Asimov.

“My parents thought science fiction was garbage, but I would secretly read under the bed covers and so all of this work is kind of a result of all that reading and NASA photographs; there’s just no end to it,” he said.

Simpson is also married to former NASA astronaut Catherine Coleman, who brought one of Simpson’s glass planet pieces into space while she was living aboard the International Space Station, he said.

“It’s ironic that my wife is an astronaut and she inspires me certainly, but I was making planets even before we met,” he said. “I like to say that I also inspired her. She just retired. She was NASA’s most senior astronaut for the last four years before she retired last year.”

Simpson said the first person to walk on the moon, astronaut Neil Armstrong, even collected his work. Simpson developed a friendship with Apollo 12 NASA astronaut Alan Bean, the fourth person to walk on the moon.

“The astronaut family is a small group of people and they are really kind of like a family,” Simpson said. “The reason why I knew Neil or any of the other astronauts is because of the connection with my sweetheart … Alan Bean just died about a month ago and he was an amazing guy. I felt like he really was a friend. He was an engineer and a test pilot, but later became a painter, so I felt like I had a lot in common with him.”

Simpson said he’s continually inspired by new astronomical discoveries, including exoplanets and asteroids.

“I’m constantly interested in news from NASA and the European Space Agency,” he said. “I was just reading today about an asteroid that is 170 miles in diameter, but it’s completely made of iron nickel. There’s more metal in this one asteroid than all the metal in our planet.”

Simpson moved to Shelburne Falls in 1976, building his studio, which consists of several different areas in the former New England dairy barn. There’s the “hot shop” where raw glass is heated to molten liquid temperatures between 2,100 and 2,400 degrees Fahrenheit. The room becomes so hot that Simpson leaves clothes to dry on a second floor loft overlooking the hot shop metal furnaces, which he also built himself.

“During the time when the furnaces are running, the heat dries clothes instantly,” he said. “In the summer they don’t dry much at all [because the furnaces aren’t running].”

Simpson said he creates his glass planet pieces by layering pieces of glass cane, smaller pieces of intricately designed and multi-colored glass that he might have spent days working on. Layer by layer, Simpson is able to design glass-shaped worlds that are gradually cooled starting at 1,000 degrees Farenheit down to room temperature to avoid a drastic temperature change, which would damage the artwork.

In the “quiet room” portion of the workshop, Simpson has indexed thousands of pieces of glass as part of his artist’s tool kit, all of which he’s created over the span of decades.

Simpson’s career path to become a glass artist wasn’t planned, he said. During the early 1970s at the age of 21, he was a senior at Hamilton College and had an opportunity through Hamilton College to leave the school for one month to learn about glassmaking.

“I had done pottery in the summertime and loved working with clay, but I decided that it would be fine to learn to blow glass,” he said. “I got permission to go to Goddard College in Plainfield, Vermont, and when I arrived at Goddard it turned out that they didn’t have a glass furnace after all or they had dismantled their glass furnace. So, I was facing the reality of living in the back of my Datsun pickup truck for a month, but in the end I decided to actually build a furnace with another student, not even knowing how to do it, and started to blow glass. I loved it so much. I basically taught myself and it was so much fun that I called up Hamilton at the end of the month and said, ‘I don’t want to come back.’”

With a total of $306 in savings, Simpson dropped out of college for a year and rented a 50-acre field in Vermont for about $22 a month, setting up a makeshift studio where he got his start professionally making glass art. Four or five years later, he said he was surprised to find that he had turned his passion for glassblowing into a career.

“In the beginning I just did it because it was freaking fun; it was just amazingly fun and interesting and intriguing and completely got my attention,” Simpson said. “It’s so difficult to blow glass that if you make anything you feel this incredible sense of accomplishment. I started doing it and I never thought it was a real career … Here I am 48 years later and to be honest with you, I’m way old enough to retire, but I really love doing this. I wake up every morning going, ‘What can I do? I’ve got this idea.’”

Simpson currently has an exhibit called “Galactic Landscapes” featured at the Berkshire Museum in Pittsfield, which is on view until Jan. 6, 2019. For more information about Josh Simpson visit www.megaplanet.com.