A few years ago, when I told my brother I was directing a production of As You Like It, he said, “That’s the one about Beatrice and Benedick, isn’t it?”

Well, no, but the confusion is understandable. Several of Shakespeare’s comedies have interchangeable titles: As You Like It, Much Ado About Nothing (the one my brother was thinking of), All’s Well That Ends Well, and for that matter, Twelfth Night.

As You Like It is the one about the exiled courtiers in the Forest of Arden and thus, along with The Tempest, Love’s Labor’s Lost and A Midsummer Night’s Dream, is wonderfully suited to be performed out-of-doors. Shakespeare & Company has recently revived its founding practice of al fresco productions, and last summer opened the Roman Garden Theatre with a compact but boisterous rendition of The Tempest.

This year’s As You Like It applies the same winning formula – a small cast cleverly doubling roles and interacting cheekily with the patrons, who surround the rustic stage on lawn chairs and raised benches as the sun sets over the Berkshire hills (performances begin at 5pm).

Allyn Burrows, in his second season as S&Co’s artistic director, fills the space with frolicsome merriment, giving his nine-member cast their heads to leap pell-mell into the Bard’s sylvan satire of court and country life. He’s set it in the Roaring Twenties, denoted by a wind-up gramophone and flapper dresses (designed by Govane Lohbauer), but that’s almost incidental to the play’s universal message of self-discovery amid adversity.

Burrows has conflated some characters and swapped several genders. Gregory Boover plays the lovelorn shepherd Silvius, who in this version is also one of the followers of the exiled Duke, played by Nigel Gore, who deftly doubles not only as his evil brother but as a gnarly old son of the soil. MaConnia Chesser plays the (traditionally male) clown Touchstone, whose dimwitted love interest, Audrey, becomes Aubrey, played by Thomas Brazzle, who (are you still with me?) is also Oliver, one of the play’s hard hearts warmed by the forest’s “physick” for the soul – and who has to make some nimble quick-changes in the last scene, when both guys are supposed to be onstage at the same time.

The play’s mainspring is Rosalind, who flees the wicked court on pain of death with her cousin Celia (a spirited Zoë Laiz) and in the guise of a boy schools naïve and handsome young Orlando (Deaon Griffin-Pressley, delightfully wide-eyed), in the art of love. As Rosalind, Aimee Doherty – a newcomer to S&Co but remembered by Valley audiences in performances at New Century Theatre – leads the cast with feisty good humor.

Ella Loudon doubles as a swanky courtier and a disdainful shepherdess, the former hilarious, the latter surprisingly restrained. I’d also like to have seen more life in Mark Zeisler’s Jacques, whose dry, matter-of-fact delivery of the ruminative “All the world’s a stage” does little justice to Shakespeare’s second-most-famous speech.

There’s much music, played on Boover’s jazzy guitar, and some Charleston-flavored dance choreographed by Susan Dibble. The up-close, intimate space and the airy sky above, recalling the open-air Globe of Shakespeare’s time, help to make this As You Like It one of the summer’s most enchanting shows.

Uncertain Principles

The Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle in quantum physics states that you can’t simultaneously locate the position and measure the velocity of a subatomic particle, and that the more closely you track one of those variables, the less predictable the other one becomes. The very act of observing it changes its behavior. Or, as one of the two characters in Simon Stephens’ Heisenberg puts it, “If you watch something closely enough, you realize you have no possible way of telling where it’s going or how fast it’s getting there.”

This is the play’s metaphorical subtext, made explicit by its title, named for the principle’s author, German physicist Werner Heisenberg, who is a character in Michael Frayn’s Copenhagen, which likewise probes the relationship between particle physics and, well, relationships.

Here, the two elusive particles are Alex, a 75-year-old Anglo-Irish butcher, and Georgie, a 42-year-old American woman living in London. He is thoughtful, self-contained and rational (“I don’t feel,” he explains, “I think”), a musical omnivore whose tastes run from Bach to electropunk, with an ironic, resigned view of life. She is excessive and uninhibited, the motormouth Yank to Alex’s taciturn Brit, quirky and whimsical to his sensible diffidence.

Here, the two elusive particles are Alex, a 75-year-old Anglo-Irish butcher, and Georgie, a 42-year-old American woman living in London. He is thoughtful, self-contained and rational (“I don’t feel,” he explains, “I think”), a musical omnivore whose tastes run from Bach to electropunk, with an ironic, resigned view of life. She is excessive and uninhibited, the motormouth Yank to Alex’s taciturn Brit, quirky and whimsical to his sensible diffidence.

After a chance encounter on a railway platform – or is it purely by chance? – Georgie relentlessly pursues Alex, both baffling and intriguing him with her kooky unpredictability and a chaotic life story, not all of which is true. She gradually punctures his solitude and he ultimately deflects her initial designs on his generosity. What begins as a cat-and-mouse game with the potential of a psychological thriller (Stephens’ inspiration was a real-life con game) dissolves into a kind of eccentric romcom, with plot turns as random and inexplicable as a quark.

The original London production, which drove the metaphorical point home by including The Uncertainty Principle as its subtitle, received mostly enthusiastic reviews, as did the 2015 Broadway version, and Shakespeare & Company’s current production as well. I beg to differ.

For me, the play and its title mainly give intellectual cover to an otherwise modest opposites-attract, May-December romance. Georgie articulates the Heisenberg Principle in relation to her estranged son, who has fled to America to get as far away from her as possible. “I watched him all the time,” she says. “He took me completely by surprise.” But the symbolism of the central relationship seems more in line with Newton’s third law of motion, as expressed in the Johnny Mercer standard: “When an irresistible force such as you, meets an old immovable object like me, something’s gotta give.”

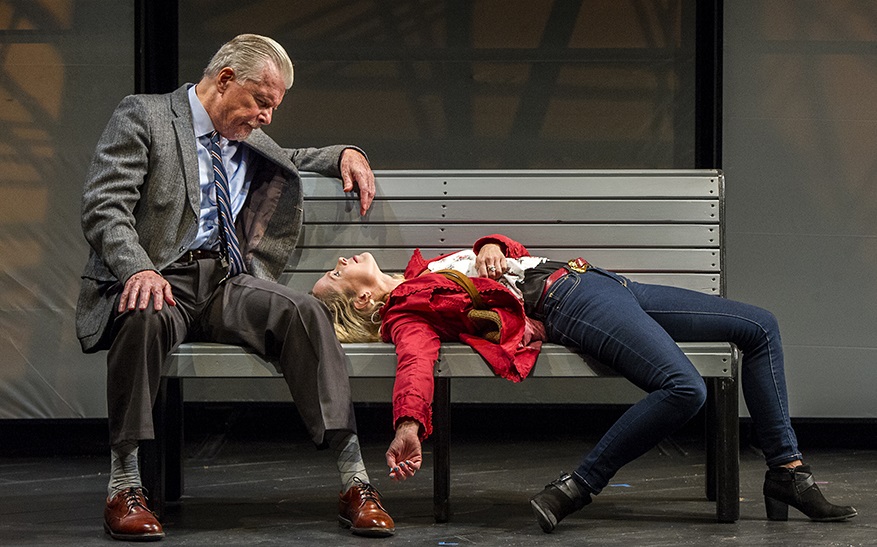

In the course of the 90-minute production, the actors never leave Juliana von Haubrich’s multi-purpose set, even for scene and costume changes – as self-contained as an atom. The performances, under Tina Packer’s direction, are as divergent as the characters themselves, and in one case even more so. S&Co veteran Malcolm Ingram gives one of his best-ever performances as Alex – understated and beautifully balanced, his sardonic and self-deprecating air masking loneliness and the scars of a long-ago broken heart.

In the course of the 90-minute production, the actors never leave Juliana von Haubrich’s multi-purpose set, even for scene and costume changes – as self-contained as an atom. The performances, under Tina Packer’s direction, are as divergent as the characters themselves, and in one case even more so. S&Co veteran Malcolm Ingram gives one of his best-ever performances as Alex – understated and beautifully balanced, his sardonic and self-deprecating air masking loneliness and the scars of a long-ago broken heart.

Tamara Hickey’s Georgie is neither understated nor balanced. Never the subtlest of performers, she gives us a Georgie who’s apparently in the throes of an extreme manic episode, with frantic, flailing gestures and mock-cutesy mugging, performed in a loud, nasal, not very accurate Noo Joisey accent. The result being that I could only wonder why Alex believes a single word she says and doesn’t run away screaming, or at least send for the health services.

What we’re intended to find in Heisenberg, I think, is the collision of two souls whose unpredictable interaction changes them both. But isn’t that what all drama is about – or, for that matter, all of life?

I wasn’t able to catch up with these shows until late in their runs. They both close on September 2nd.

As You Like It photos by Nile Scott Studio

Heisenberg photos by Daniel Rader

If you’d like to be notified of future posts, email StageStruck@crocker.com