In Shakespeare’s time, actors wore their own clothes with token costume pieces, they performed on a bare platform, and they were all male. Those facts are the springboard of Elizabeth Williamson’s vision for her production of Henry V, which plays at Hartford Stage through Nov. 11.

Or, make that re-vision. She has adopted and adapted those conventions for her own use and our own time, connecting that English king’s 15th-century war of conquest to the present day.

Her actors wear ordinary street clothes (we first see the king in t-shirt and jeans), donning olive-drab combat jackets to go to war and blue tunics for the French court. Nick Vaughan’s set is an echo of the Globe’s “wooden O,” enclosed by in-the-round seating – a rare if not unique configuration for Hartford. On the bare expanse of floor is painted an outline map of Britain and Europe focusing on England and France, where the “two mighty monarchies” meet in battle.

Her actors wear ordinary street clothes (we first see the king in t-shirt and jeans), donning olive-drab combat jackets to go to war and blue tunics for the French court. Nick Vaughan’s set is an echo of the Globe’s “wooden O,” enclosed by in-the-round seating – a rare if not unique configuration for Hartford. On the bare expanse of floor is painted an outline map of Britain and Europe focusing on England and France, where the “two mighty monarchies” meet in battle.

Seizing the cross-gendered Shakespearean convention, where the women were played by beardless boys, Williamson makes a bold contribution to the growing contemporary practice of gender- and color-blind casting. She fields a 15-member ensemble, of whom seven are women and six are people of color, most of them taking on several of the play’s 34 characters – as Shakespeare’s company did.

Shakespeare himself invites – indeed, insists on – this all-in suspension of disbelief. He opens the play with a Chorus figure who first apologizes for the “flat unraised spirits” who presume to present such a grand historical pageant “on this unworthy scaffold.” Then he asks us to enlist our “imaginary forces … piece out our imperfections with your thoughts,” imagine armies massing on “the vasty fields of France” and one man standing for a thousand.

Shakespeare himself invites – indeed, insists on – this all-in suspension of disbelief. He opens the play with a Chorus figure who first apologizes for the “flat unraised spirits” who presume to present such a grand historical pageant “on this unworthy scaffold.” Then he asks us to enlist our “imaginary forces … piece out our imperfections with your thoughts,” imagine armies massing on “the vasty fields of France” and one man standing for a thousand.

This is the kind of theater I love best – theater that frankly acknowledges the audience (we are addressed as witnesses in the scenes at court) and uses its low-tech qualities to aesthetic advantage. Some things about this production are thrilling. The propulsive energy and fluid staging, demarcated by Stephen Strawbridge’s lighting, capture the story’s insistent momentum, and there’s a strong sense of fellowship among the ensemble.

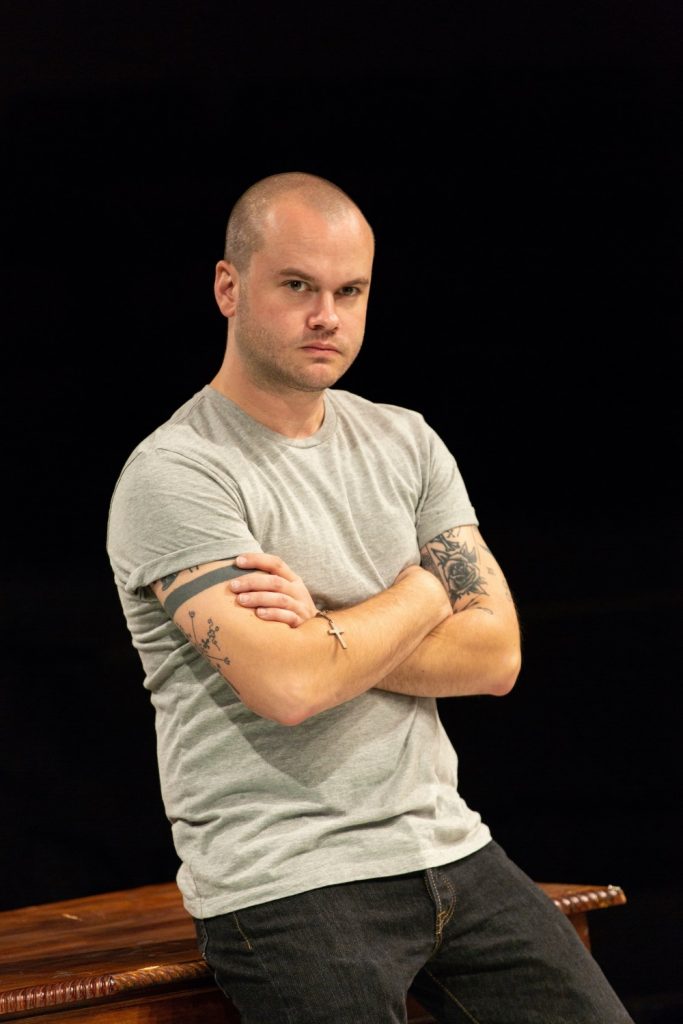

Stephen Louis Grush has some effective moments as Henry, but I couldn’t see the character arc, the coming-of-age story of a playboy prince slowly growing into maturity as a warrior-king, and many of his lines are delivered with too much volume and too little shading.

Stephen Louis Grush has some effective moments as Henry, but I couldn’t see the character arc, the coming-of-age story of a playboy prince slowly growing into maturity as a warrior-king, and many of his lines are delivered with too much volume and too little shading.

The opportunities for comic relief with the barflies Prince Hal used to carouse with are squandered in caricature, neither ironic nor amusing. These episodes also illustrate another missed opportunity – to create a coherent performance style. I got the impression the director established her concept, its feel and flow, then mostly left her actors to their own devices.

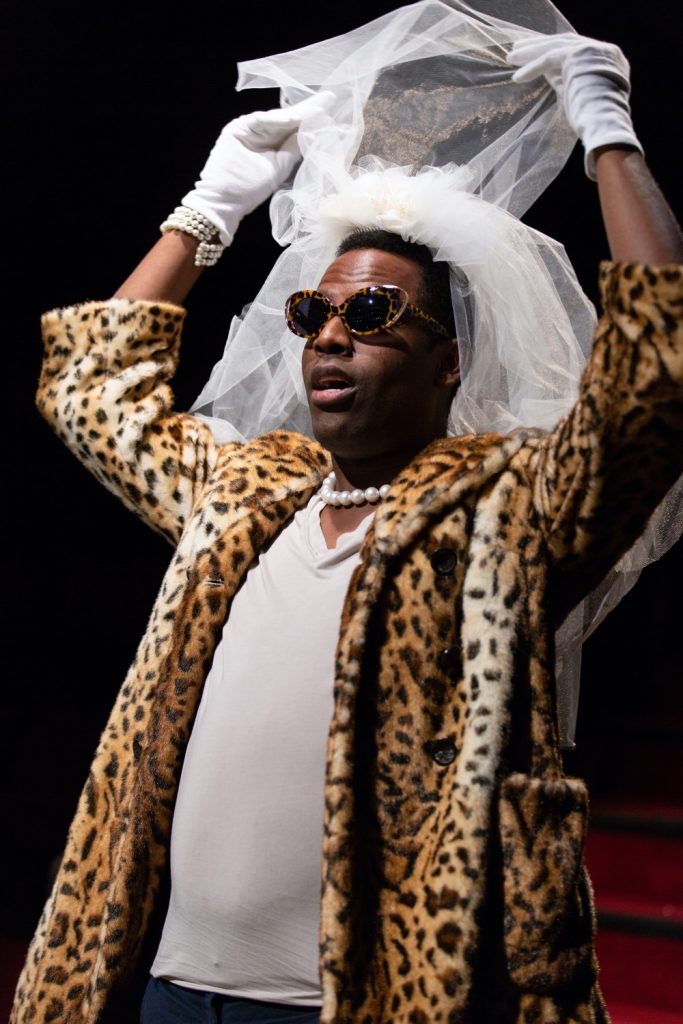

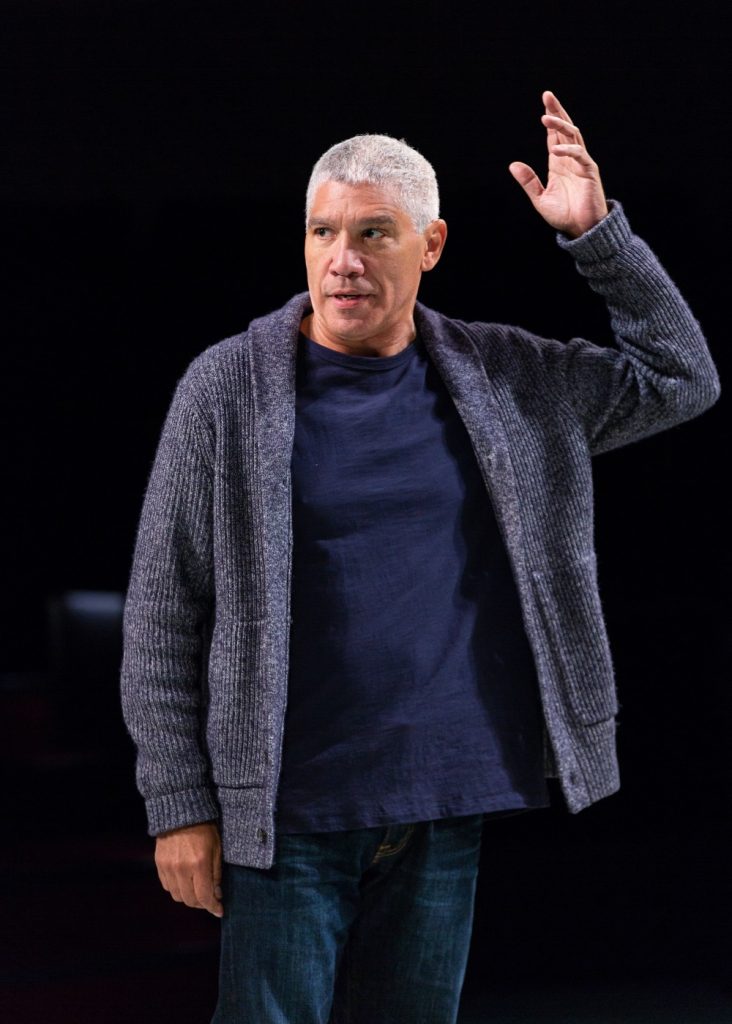

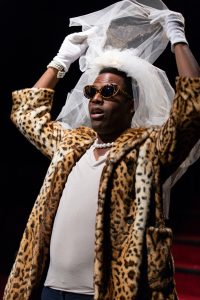

This is most evident in Miles Anderson’s overblown performance as the rascally rogue Pistol and  Baron Vaughn’s as the tavernkeeper Mistress Quickly, who becomes an arch, swishy drag queen. Peter Francis James, majestic of voice and grandiloquent in tone and gesture, sets the Chorus apart, perhaps as a nod to Shakespearean “original practice” or to place the modern-dress action within an epic frame.

Baron Vaughn’s as the tavernkeeper Mistress Quickly, who becomes an arch, swishy drag queen. Peter Francis James, majestic of voice and grandiloquent in tone and gesture, sets the Chorus apart, perhaps as a nod to Shakespearean “original practice” or to place the modern-dress action within an epic frame.

I also wish the actors had done more to distinguish between their multiple characters physically and vocally. There were times when I, who know the play pretty well, couldn’t tell who was who. Exceptions include Nafeesa Monroe as the haughty French king and a terrified battlefield prisoner, and Evelyn Spahr as a wide-eyed boy soldier and the poised Princess of France. I admired Liam Craig’s gruff, plain-spoken take on the text, but couldn’t see much difference between the barfly Bardolph and the soldier Gower.

Dramaturg Yan Chen’s program note discusses the continuing argument over the play’s meaning and intent. Is it a jingoistic glorification of war and nationalism, written to “stiffen the sinews” of the nation against a foreign foe and justify imperial rule? Or does an anti-war message run through its heroic structure, in which the king’s footsoldiers question his motives, his officers wrangle among themselves, and the monarch himself is not always valiant, slaughtering prisoners and taking the French princess as war booty?

Dramaturg Yan Chen’s program note discusses the continuing argument over the play’s meaning and intent. Is it a jingoistic glorification of war and nationalism, written to “stiffen the sinews” of the nation against a foreign foe and justify imperial rule? Or does an anti-war message run through its heroic structure, in which the king’s footsoldiers question his motives, his officers wrangle among themselves, and the monarch himself is not always valiant, slaughtering prisoners and taking the French princess as war booty?

Of course, as so often with Shakespeare, it’s both – a celebration and critique of conflicted human nature, in which all of us, regardless of color or gender, can see ourselves.

Photos by T. Charles Erickson

If you’d like to be notified of future posts, email StageStruck@crocker.com